“We Drink from Our Own Wells: The Spiritual Journey of a People”, is a title of a book written by the Latin American foremost theologian, Gustavo Gutierrez in 1983. It was a book aimed to provide spiritual basis for Gutierrez’s Magnus opus, “A Theology of Liberation”, which appeared in Spanish in 1971 and soon became a charter for many Latin American theologians and pastoral workers.

In the introduction to “We Drink from Our Own Wells”, Gutierrez tells us that the title of his book expresses the core idea it describes: St. Bernard of Clairvaux’s observation: “Everyone has to drink from his own well.” Gutierrez legalized from the beginning that any theology on society and politics that does not come out of an authentic encounter with the Lord, and the concrete living experience of the people, can never be fruitful. In 1971, he wrote:

“Where oppression and the liberation of humans seem to make God irrelevant – a God filtered by our longtime indifference to these problems – there must blossom faith and hope in Him who comes to root out injustice and to offer, in an unforeseen way, total liberation.”

‘To drink from your own well’ is to live your own life in the Spirit of Jesus as you have encountered him in your concrete historical reality. It is to draw water of life from him and from your own historical concrete experience and that of your people in their struggle for freedom and restoration. It is to be immersed, full-time in bearing witness to Christ in the historical concrete reality – the liberative praxis and struggle for freedom and restoration of wounded humanity of your people.

More than ten years were to pass before Gutierrez had the opportunity to develop this spirituality fully, but it was worth waiting for. “We Drink from Our Own Wells” is the nuanced articulation of the Christ-encounter as experienced by the poor of Latin America in their struggle to affirm their human dignity and claim their true identity as sons and daughters of God.

Gutierrez’s “We Drink from Our Own Wells”, has nothing to do with abstract opinions, convictions, or ideas, or prejudices. No. Rather, it has everything to do with the tangible, audible, and visible experience of God, an experience so real that it can become the foundation of a life project. As the First Epistle of John puts it:

“What we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked upon and our hands have touched – we speak of the word of life.” (1John 1:1-2).

A similar metaphor of Gutierrez’s “We Drink from Our Own Wells”, is more eloquently, presented in the Fourth Chapter of John’s Gospel account of Jesus’ meeting with the Samaritan woman at the well. Jesus’ meeting and conversation with the Samaritan woman at the well, on the theme of Himself as the ‘Living water’, tells us about the type of complete liberation and restoration that waits us in Jesus if only we could draw water from our own wells through Him.

That is, the type of living water Jesus offers us as Nigerians if only we could begin to draw water from our Nigerian wells – concrete historical reality and experience as Nigerians, and not from the Rwandans or any other well. It is from our own wells – in our backyard, villages, towns and cities that Jesus is waiting for us, to give us living water that we may not be thirsty again (cf. John 4: 13-14).

In our own wells as Nigerians, Jesus is waiting to ask us water to drink. He is waiting to meet with us, and to converse with us as he did with the Samaritan woman. Moreover, in that well at our village, Jesus is waiting to convert us and transform our lives forever. The Samaritan woman had been living in denial of her personal journey and history until she encountered Jesus at the well (Cf. John 4: 15-21).

It is obviously that the unique and renewing encounter with the living Christ in the struggle for freedom and restoration of our wounded humanity, as Gutierrez writes in “We Drink from Our Own Wells”, “is like living water that springs up in the very depths of the experience of faith of persecuted people.” It is like living water that reveals the truth about our past in order to set us free forever. Lies and denials of our historical past – living in denials of our concrete reality and historical experience as individuals and a people have no place in the wells of living water Jesus is offering us in Himself.

The Problem

In the light of the above, one may ask, ‘why do we have to go this far’ to introduce our topic and choice of Gustavo Gutierrez’s book, “We Drink from Our Own Wells”, as the starting point for our present article? The reason is obvious:

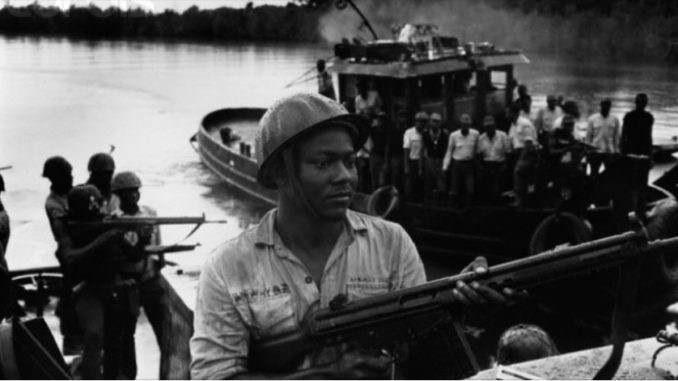

In the present article, we wish to address the deceptive narrative pervading Nigeria’s body polity today. That is, the dangerous narrative, which aims often, at suppressing the story and experience of the victims and survivors of Nigeria-Biafra War (1967-1970), and jumps ahead to cite Rwanda as a warning to what is happening presently in our country!

Without linking the present reality of Nigeria with its’ past – the true story or rather history of Biafran pogroms and war, the country can hardly make any headway. The government continued suppression of the Biafran story is the bane of Nigerian state today.

Without national reparation and atonement for the Biafran pogroms committed during the Nigeria-Biafra War (19767-1970), we are not yet ready for nation-building in Nigeria. As I have been saying in my previous articles, ‘the salvation of Nigeria as a nation state is in its suppressed history of the Nigeria-Biafra War.’

As a nation, Nigeria may continue to suppress its past historical memory to its own detriment and self-destruction. Again, without atoning for its sins of the past committed against innocent civilians during the Biafran pogroms and war, Nigeria will continue in its present backward slide until thy kingdom come.

In the midst of all these, it is always frustrating for people of good conscience, to observe how most Nigerians have continued to use Rwanda as a historical paradigm for the Nigeria of today, forgetting that ‘Before Rwanda, there was Biafra.’

Sometimes, we overlook our own sufferings and concrete historical experience to exalt those of outsiders. The fact that we have survived our own sufferings does not mean that we should overlook what we had suffered and are still passing through in Nigeria today. It doesn’t mean either that those other Nigerians who did not experience what Biafrans experienced and have continued to experience in Nigeria, should feel offended each time the survivors of the Biafran pogroms and the genocidal Nigeria-Biafra War recount their story or remember their relatives who were victims of the war!

Recently, I came across a comment someone made against a well-researched article of one Akin A. Ajose-Adeogun, entitled, “Felix Houphouet-Boigny and Nigerian/Biafran War.” However, before we discuss the comment, it suffices to have a bird’s eye view of the central argument of Ajose-Adeogun’s article:

Akin A. Ajose-Adeogun, in the introductory part of his article “Felix Houphouet-Boigny and Nigerian/Biafran War”, said:

“We have suffered for fifty-one years now, the consequences of our leaders’ naivety and blunders in not holding the FGN to its words on the Aburi Agreement that had transformed Nigeria into a confederation, which is the only workable structure for a country that is an ill-assorted ragtag of mutually hostile ethnic groups and conflicting ideologies. … I understand the fears, at the time, of the federal bureaucrats from the minority ethnic nationalities …. Who had advised Gowon to unilaterally revise the Aburi Agreement [by introducing ss.70 and 71, which reasserted the power of the FGN over regions, thus abrogating the confederal nature of Nigeria agreed at Aburi]. But could their genuine fears of domination by the majority ethnic nationalities in the regions not have been simply addressed by arguing for the creation of more states – as, in fact, occurred later on 27 May 1967?”

Going further, Ajose-Adeogun says that what we appear to be witnessing now in Nigeria is the denouement Houphouet-Boigny had feared: “the southward encroachment of West Africa’s Islamic Sahelian belt, which he felt that the ‘able and intelligent Igbo’ had an important part to play in preventing.” (See Michael Gould, The Biafran War: The Struggle for Modern Nigeria, I.B. Tauris and Co., 2013).

Houphouet-Boigny was an extremely astute leader who was highly regarded across the French-speaking world. At a time Nigerian leaders saw their problems in a narrower sense of a misunderstanding among ethnic groups in the country, Houphouet-Boigny saw it as a struggle between two rival systems – Islam and Christianity – that has now, historically, lasted for some fourteen centuries. He had seen this as an emerging continental or global problem. And the Ivorian crisis and civil war was about maintaining the Ivorian identity in the face of Muslim migration from the Sahel. “We see the same problem today in the Western world, Kenya, Myanmar (Burma), Russia’s Caucasus region, Ethiopian Eritrea, Indian Kashmir, Chinese Sinkiang, and Yugoslav Kosovo, etc.”

It was on this basis that Ivory Coast supported Biafra and influenced France and Gabon into doing the same. Ajose-Adeogun adds in his article that, “The minority ethnic groups and the Yoruba who had both inadvertently helped the Islamic North to entrench a hegemony during the so-called war of Nigerian unity now seek our former decentralized pre-1966 federalism as a minimum demand, as they increasingly feel the lash of the Islamic North’s political stranglehold.”

In conclusion, he opined that, while on the one hand, “the non-Igbo South-South and Central Nigeria (Middle Belt) committed an epic historical blunder’, ‘the Igbo, at a cost of thousands of dead in the pogroms of May and September to October 1966, purchased a confederal system of government for Nigeria.’ This system of government was, and still is, the most workable one for Nigeria. Unfortunately, the rest of the country did not realise it at the time. An incongruous and unholy alliance was cobbled up to fight for a non-existent unity, as events of the last fifty-one years have dubitably made clear.”

Akin Ajose-Adeogun concludes his insightful article by saying, “That the so-called war of Nigerian unity resulted in a military victory for the Islamic North, but a moral victory for the Igbo. Ironically, with the benefit of hindsight today, it is the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria that suffered the greatest defeat. In addition to sustaining a massive moral defeat, both regions also sustained a massive political defeat.” The author of the article concludes his analysis thus:

“Consequently, I do not know whether it is the non-Igbo and Central Nigeria that should commiserate with the Igbo for the massive loss of lives, or whether it is the Igbo that should commiserate with the non-Igbo South and Central Nigeria for the loss of their souls and possibly an even greater loss of lives in the future to a mistake that could probably have been avoided at small cost in 1967. I’m inclined towards the latter position as we approach another critical juncture in our history.” (See Akin A. Ajose-Adeogun, “Felix Houphouet-Boigny and the Nigerian/Biafran Civil War”).

Akin A. Ajose-Adeogun, the author of the article we discussed above is from the Southwest region as his name indicates. Surprisingly, however, the most poignant comment against his article came also from someone from the same geopolitical region. This is to show you how far Nigeria and most of its citizens from those regions that fought against Biafra during the civil war are still from embracing the truth, and engaging realistically in dialogue with Nigeria’s own past, even if it is a bitter past.

Thus, to buttress the central argument of our present article, we have decided to make a brief reference to the comment the person made against Ajose-Adeogun’s well-researched article. This is what the person commented, among other things, against Ajose-Adeogun’s article:

“Blame game…. Blame game… One perspective among many. I keep asking why do we need to circulate these things that reinforce ethnic hatred. It might [look] like a good analysis, but it is not infallible, it is only a perspective in a complex situation. My fear is that a genocide is imminent in our dear country and my greatest fear is that priests and religious would be caught in the virtuous circle of violence. It seems to me that we have not learnt much from Rwanda’s lesson. …”

The above comment takes us a step forward, for the discussion is not simply that we should avoid any open discussion about our historical past and experience as a people or nation; suppress our dangerous and pathetic historical memory, but also that priests and religious should not participate at all in political discussion of their country.

Moreover, the author of that comment reinforces another major concern of our present article, namely that most Nigerians easily cite Rwanda, as she did, instead of Biafra as a reference point while speaking of likely dangers that may result from the unfolding political scenario of Nigeria.

In the same vein, in what looks like overzealous outburst to fight against what she calls ‘spreading ethnic-hatred’ (although, blindly), she appeared to be against those victims of violence and oppression, who recount their stories, denounce openly the injustices and dehumanizing experience they had passed through at the hands of terrorists or their oppressors and tyrannical regimes!

In addition, for the author of that comment, modern means of mass communication should not be extended to victims of violence, because, according to her, they may abuse it, use it to spread, what she called ‘ethnic-hatred.’ Victims of violence and unjust regime, who share their horrendous experiences with the larger public through mass or social media, according to her, are spreading ‘ethnic-hatred.’ Moreover, people who discuss or spread news about the ongoing injustices in the land, those who discuss the historical memory of their nation, if we are to follow the prescriptions of the author of that comment, should be banished from doing so in the media, especially social media. What a piety?

It is in the light of the above, we would like to offer the following response:

‘Before Rwanda, there was Biafra.’

Before Rwanda, we had Biafra! This is a historical fact. If Nigeria must learn, it must be from its own history and not from that of faraway Rwanda, no matter how appealing the latter may appear to some Nigerians today. As Gustavo Gutierrez, the Peruvian, Latin American theologian we cited earlier, said, “We must drink from our own wells.”

Rwandan genocide of 1994 claimed an estimated number of 1 million lives of the Tutsi. Too bad. Christians killing one another! However, the Biafran pogroms and genocide (1967-1970) claimed an estimated number of 3.5 million lives, mostly of Igbos and other Easterners, killed by combined forces of coalition of other Nigerian Ethnic-Nationalities from the North, Middle Belt and the Southern regions of the country, under the command of Federal Military Government of General Yakubu Gowon and British Establishments.

In the face of these historical facts, one wonders why some people in Nigeria will continue citing a faraway Rwanda as example of where Nigeria should learn the lesson of history, while here in Nigeria, we have our own Biafra pogroms and genocide? Why would some Nigerians choose to continue to suppress the story of Biafran pogroms, the Nigeria-Biafra genocidal war, which till date, is the most horrendous crime against humanity (after the Jewish Holocaust) committed in the 20th century.

Worse still, Biafra pogroms were committed by Nigerian State, assisted by a world power, Britain and its allies. It was a crime against humanity committed against Africans of a particular ethnic-group, the Igbo. In the midst of this, the federal government of Nigeria orchestrated the use of narrative of lies, denials and hate language, all formulated against the Igbo to justify the war and their marginalization in the scheme of things in Nigeria thereafter and till date.

Today, the same Nigerian state and federal government, is still denying that the Biafran pogroms and genocide happened. Unfortunately, some people on the other side, including priests and religious have bought into that government narrative of lies and denials. What a pity?

The fact that one’s own ethnic and religious group in the Nigerian state, never experienced exactly, what the Igbo experienced during the Nigeria-Biafra War, and are still passing through in the country today, does not in any way at all diminish that experience in Nigeria’s history. It does not also mean that we should banish them (Igbo) from telling their Biafran story and experience as a people. Nor does it justify the government continued militarization of the Southeast region or the sending of Python Dance military battalions by the Buhari administration to kill Igbo youths whenever they gather to remember their people killed during the pogroms and the civil war.

As one author recently said, ‘Time has come for priests and religious to rise up and join hands in condemning these evil things going on in the country today.’ The fact is that nobody can serve two masters at a time as the Bible teaches. Speaking out of our problem is even a way of finding out a solution. We should not think that because God created man and put him in the Garden of Eden, man should not work out his own salvation as a creature of God. To think so is to negate the event of Exodus – the struggle of Moses and people of Israel in Exodus to free themselves from servitude and slavery in Egypt.

Today, Nigerian government and some individuals in the country, deceitfully, pretend to be fighting hate-speech. But in reality, the government and its sympathizers are promoters of ethnic-hate and hate-speech through their actions and inactions in the face of ongoing persecutions of some targeted indigenous ethnic-nationalities and Christians in the country. At the same time, the Nigerian government and their sympathizers have refused to acknowledge that it was Nigerian state narrative of ethnic-hate against the Igbos that led to the Biafran pogroms and genocidal Nigeria-Biafra War.

You cannot be feeding on ethnic-hate against a particular ethnic-group you killed over 3.5 million of their people during the Nigeria-Biafra war, and at the same time be accusing the same victims of your ethnic-hate and pogroms of propagating hate! This is the highest form of narrative of deceit, Nigerian state has been trending and propagating to its citizens over the years against the Igbo.

Methinks, it is the duty, not just of politicians and ordinary citizens, but especially, of priests and religious to speak out and condemn this malignant deceit that has eaten deep into the very fabric of Nigerian state in its relationship with the Igbo nation and people.

Chinua Achebe in his landmark small book, “The Trouble with Nigeria”, quoted a statement accredited to one distinguished political scientist from a “minority” area of the south who pronounced some years ago that, “Nigeria has an Igbo problem.” Every ethnic group, Achebe opines, is of course something of a problem for Nigeria’s easy achievement of cohesive nationhood. But the learned political scientist Achebe quoted, “no doubt saw the Igbo as a particular irritant, a special thorn in the flesh of the Nigerian body-politic.”

The conclusion here is that ‘Nigerians of all other ethnic groups will probably achieve consensus on no other matter than their common resentment of the Igbo.’ Modern Nigerian history has been marked by sporadic eruption of anti-Igbo feeling of more or less serious import. However, it was not until 1966-7, when it swept through Northern Nigeria and rest of the country like “a flood of deadly hate”, that ‘the Igbo first questioned the concept of Nigeria which they had embraced with much greater fervour than the Yoruba or the Hausa/Fulani.’

The Nigeria-Biafra War gave Nigeria ‘a perfect and legitimate excuse to cast the Igbo in the role of treasonable felon, a wrecker of the nation.’ When the attempt of the secessionist state of Biafra was defeated in January 1970, in spite of Gowon’s declaration of ‘no victors no vanquished’, yet some still wanted to punish the Igbo all the same. This is seen by the banking policy introduced immediately after the war by the federal government, which nullified any bank account, which had been operated by any Igbo during the civil war.

This had the immediate result aimed at pauperizing the Igbo middle class and earning a profit of £4 million for the Federal Government Treasury. If there was ever a measure put in place to stunt, or even obliterate, the economy of a people, this was it.

After that outrageous charade, the Federal Government banned the importation of second-hand clothing and stock-fish – two trade items that they knew the burgeoning market towns of Onitsha, Aba, and Nnewi needed to re-emerge. “Their fear was that these communities, fully reconstituted, would then serve as the economic engines for the reconstruction of the entire Eastern Region.”

This was followed by the infamous Indigenization Decree of 1974, which soon afterwards completed the routing of the Igbo from the commanding heights of the Nigerian economy, ‘to everyone’s apparent satisfaction.’ The idea of the Decree was ostensibly pushed through by the leaders of the federal government in order to force foreign holders of majority shares of companies operating in Nigeria to hand over the preponderance of stocks, bonds, and shares to local Nigerian business interests.

The move was sold to the public as some sort of “pro-African liberation strategy” to empower Nigerian businesses and shareholders. However, as Chinua Achebe reminded us, the chicanery of the entire scheme of course was quite evident:

“Having stripped a third of the Nigerian population of the means to acquire capital, the leaders of the government of Nigeria knew that the former Biafrans, by and large, would not have the financial muscle to participate in this plot. The end result, they hoped, would be a permanent shifting of the balance of economic power away from the East to other constituencies. Consequently, very few Igbos participated, and many of the jobs and positions in most of the sectors of the economy previously occupied by Easterners went to those from other parts of the country.” (Chinua Achebe, “There Was A Country”, Penguin Press, London 2012, p.235).

This is just an iceberg of anti-Igbo policy and hate alive in Nigeria today, and which is not about to go away. Pretending it does not exist is not a reliable strategy. Because at the long run, we shall continue to have more victims of it without anybody taking responsibility for such a crime against humanity. The best thing to do therefore is to discuss it in the open with a view of finding lasting solution to it.

Moreover, with the prevalent narrative of deceit, lies and denials in Nigeria’s governance culture that sustains such anti-Igbo policy and hate, it is obvious, overcoming it won’t be easy even for many religious leaders, including pastors, priests and religious from other ethnic-groups, trapped into it. Again, overcoming ant-Igbo policy and hate as well as resentment in Nigeria under the present dispensation of a notorious lopsided federal government, is a herculean task. It may require sustained prayers and public conscientization, which I am sure, no Nigerian government will be prepared to buy into.

In other words, it may be very difficult for those other Nigerians who have been fed all these years with a false narrative of the Nigeria-Biafra war to appreciate the way Easterners feel about the happenings in Nigeria today. And especially, how a typically Igbo feels about the inability of the Nigerian State to acknowledge the atrocities of the Nigeria-Biafra War, especially the genocide committed against the Igbo. That over 3.5 million killed during the Biafran pogroms and Nigeria-Biafra genocidal war itself have not been accorded State Burial and annual Remembrance Day celebration by the Nigerian State, the way it pains an average Igbo may be difficult for most Nigerians on the other side to comprehend.

In fact, those Nigerians who want the victims and survivors of the Biafran pogroms to forget all about it and move on without addressing those historical wrongs and evils in the land, certainly will find it difficult appreciating the present worries of some conscientious Nigerians about the current happenings in the country. There is a debt, you owe to your dead ones, especially, those violently and unjustly killed and massacred for no fault of theirs by the state and evil men.

Methinks that those who express those worries and point to the unhealed historical wrongs of the Biafran pogroms have really, therefore have genuine concerns, born out of true patriotism for the fatherland. Suppression of our historical memory – Nigeria’s most tragic past, is not a patriotic act. For any well-meaning Nigerian, history of Biafran pogroms committed by the Nigerian state, far outweighed the usual ‘conspiracy’ reference to Rwanda by some uninformed and docile Nigerians.

The question we need to ask is this: ‘Why is it that Nigerian state, unlike Rwanda, has continued to suppress any talk on the Biafra pogroms and genocide (1967-1970)?’ And why is it that Nigeria, unlike Rwanda is yet to honour or rather institute an annual Remembrance Day in Honour of the victims of the Biafran pogroms and the genocidal war?

Again, why is it that, unlike Rwanda, Nigeria is yet to understand that its’ future as a nation state, rests squarely, on how it treats the victims of state sponsored genocides and ethnic-cleansings? Does it worry us that after Biafra pogroms, we still experience in Nigeria today, ethnic-cleansings in the Middle Belt and Southern Kaduna, among others? What lessons have we as a nation learned from the Biafran pogroms of the ’60s? Perhaps, nothing. And yet people are talking of going to Rwanda to learn while we have not studied dispassionately our own Biafra pogroms and genocide, and learn from its’ history? In my estimation, this is the problem with Nigeria.

As Wole Soyinka once said, ‘until Nigeria acknowledges the wrongs it has done to the Igbo’, the country will continue to live in denial and wallow in darkness. The prevalent narrative of deceit and denials is the monster, Nigerian state has to fight and defeat if it wants to make any headway in the 21st century.

At least, the country could begin from here to address its’ problems. Otherwise, some people, for no fault of theirs other than wrong narrative they have been fed with all these years, will continue to blame the victims and survivors of genocides in Nigeria as the architects of their own fate. And be accusing our intellectuals who discuss most of those issues from the point of view of our ‘suppressed history’, as playing to the gallery of ‘blame game.’

Such an unmitigated accusation, for me, is a flight to avoid digesting the real problem with Nigeria, a denial of our sad and pathetic history, a sad history of Nigeria that we have to battle with and defeat if as a nation state, Nigeria must make some positive progress today. That is, if we mean to overcome our present predicament as a nation, which is to help one another to begin to see clearly that we had all the years been fed with false narrative. And that there is need to free ourselves from it and begin to fight against those evil things and bad leadership in the land that have all these years been deceiving the Nigerian people, maligning them against the victims of one of the most horrendous crimes against humanity ever committed in modern history.

This is a challenge not only to the so-called politicians, but to everyone of this age, including pastors and bishops, indeed all religious leaders (priests and religious included). We all need to set our priority right, especially to avoid false piety and wrong interpretation of Nigeria’s problem. Otherwise, a good number of our pastors, priests and religious may be playing innocently, into the traps of corrupt politicians without knowing it.

Moreover, participating in socio-political debate of one’s country should not be confused with the Church’s teaching that counsels priests and religious not to participate in partisan politics. These are different things. By the way, the political theories, disciplines and the social setup of modern European society, came principal from the writings and works of their priests and religious, especially from the Medieval times, but more importantly, during the Enlightenment or Renaissance Europe. Important Euro-American universities, e.g., Oxford, Soborne, Harvard, La Sapentia (Rome), Cambridge, and many others in the German world, and elsewhere, were all founded by the Church and used as universities from where priests and religious became the pillars that gave Europe it’s socio-political theories that gave rise to the social setup we see and admire today in the West.

In fact, in our African case, one may say that with the vocations boom in the continent today, and rise of Christianity also, perhaps, African priests and religious are challenged to play a similar role in their context, to be part of ushering in a new political system and social setup in our various countries.

Defending a failed structure or leadership, and asking priests and religious who voice out their frustrations against same to shut up their mouth, I think, leaves much to be desired. The right thing, one would suggest, is that priests and religious must be part of the debate, condemn the evil leadership in their country, and proffer a way out towards creating an equitable and just society.

This has been the history of priest-scholars and theologians in the church down the ages. This was what gave rise to Augustine’s “City of God“, his critique of the corrupt ancient city of Rome vis-a-vis his call for a New City of God in Christ to be championed by the persecuted Christians of the then Roman Empire. The same tendency we found in Thomas Aquinas’ “Summa Theologiae.” Aquinas chose to baptize the pagan Greek City state politics, whose influence had refused to leave even the ‘Christian Europe.’

German philosophers, majority of whom were priests, did the same for Europe during the Enlightenment Era, between 18th and 19th centuries. In our time, Latin American priests and religious, no doubt, were a force to reckon with in the fight against dictatorship and communist regimes in that part of the world in the late 20th century. Indian priests and religious are equally a force to reckon with in the emerging Indian egalitarian society.

Unfortunately, it is only in Africa that people still see priests and religious as Sacristy artisans, whose only mission apart from liturgical celebrations, is to say nice things about their political leaders, even when the politicians are proven dictators, corrupt leaders and tyrants of first order. Not even in the medieval times is such a thing contemplated. This is the tragedy of Africa, not only of Nigeria. May God enlighten us as a people!

Conclusion

Central to Nigeria’s historical memory today, is the Nigeria-Biafra War, especially, the pogroms committed against the Igbo by the Nigerian State. It is from that historical reality and experience we must learn to drink water from as a nation and people in addressing the current political imbroglio besetting the country. It is also the ‘wells of water to drink’, from which as concerned citizens, we offer our criticisms and proffer solutions to the country’s present socio-political problems.

Criticising Nigeria’s long years of neglect of this historical memory today, for me, is a way of trying to help the country return to the drawing board, if it really wants to fix its shattered house as a nation state. This is a patriotic act, which is not the preserve of politicians, neither is it a ‘no go area’ for priests and religious. Rather, it is a godly thing for every conscientious citizen to do for the sake of one’s own country and people.

This is the core message and idea of Gutierrez’s book, “We Drink from Our Own Wells”, with which we started this article. “We Drink from Our Own Wells” means been immersed in the daily experience of one’s own people and in their concrete historical reality and struggle for liberation through faith in Jesus Christ.

As Nigerians, we must learn to ‘drink from our own wells’, from our own concrete reality and historical memory as a people and nation. Nigerians are invited to learn to ‘drink from their own wells.’ This is recognition of the relevance of the historical memory of our country in nation-building and in tackling the country’s present problems and search for a new vision as a nation state.

END

Be the first to comment