Border closures have proven to be a practical means to contain and limit the spread of the coronavirus in most countries. However, the restricted movement that results from state and national border closures hinders the effective flow of supply chains and distribution channels.

This is especially relevant in the agricultural sector where market linkages have been broken, leading to higher levels of waste on farms, food shortages and price hikes in the urban markets. National border closures have also reinforced the importance of local production and food security. But how can we ensure that smallholder farmers are able to operate efficiently and effectively to ensure our nation’s food security?

The agriculture industry is as reliant on changing weather patterns and seasons, as it is on free movement- of farmers, inputs and produce. When Oriyomi plants his yams on his farm in Akure in November, he travels from his hometown in Oyo; it often takes him a few weeks to complete the planting. But once this is done, he returns to his family in Oyo. Approximately six months later, the time comes for the harvest, and Oriyomi must return to Akure. Ordinarily, this process would require nothing more than transport fare, and a few days. This straightforward activity is now hindered by closed state borders, police checkpoints, and the increased requirement for Oriyomi to prove that he is a farmer.

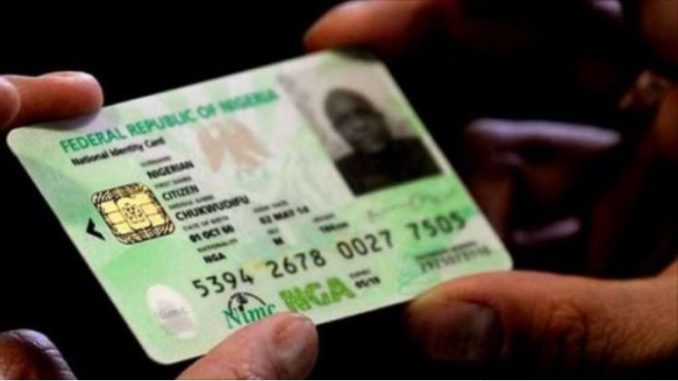

There is no doubt that the smallholder farmer – like food suppliers and distributors – is an essential worker. But without any formal form of identification to prove this, many smallholder farmers are unable to get to and from their farms or markets to distribute their food produce. These breaks in supply chains and their continued operations could be detrimental to our sustained welfare across the country. The difficulties experienced by the smallholder farmer show the far-reaching impact of Nigeria’s lack of progress with regards to identification strategies.

The National Identification System in Nigeria has experienced its fair share of complexities. The challenges stemmed from not having a singular agreed approach to establishing a clear ‘image’ of our citizens. This resulted in multiple systems and offices providing valid forms of identification with varied identification metrics and databases – from telecommunications service providers to electricity distributors to the National Immigration Service, and then the financial institutions.

Ultimately, the system becomes strained by the inability to determine the foundational metric through which to assess identity; and more so, through which to gain access to all the other aspects of an individual’s identity. Thus, the role of the National Identity Management Commission (NIMC) as the harmoniser of all existing identification information, from Ministries, Departments and Agencies, is an invaluable asset.

The 2017 regulations released by NIMC introduced the National Identification Number (NIN) as acceptable identification for a broad base of activities across sectors and industries, including for registration, purchase, applications, licensing, and obtaining passports. Two years later, the Director-General of NIMC further reiterated the Commission’s plans to provide lifelong unique identification to all Nigerians, at home and in the diaspora, leveraging the advancements in digital technology to improve coverage and enhance the sustainability of the approach. The progress has been slow.

In May 2019, NIMC reported that it had achieved approximately 31% of the harmonisation of the Bank Verification Database (BVN) with the National Identity Database. Beyond the delayed rate at which these developments are being made, there is the greater challenge of prioritization. Most marginalized populations struggle with engaging with formal structures and institutions due to the requirement for valid forms of identification; as a result, they remain marginalized and excluded.

The national identity system in India called the ‘Aadhar’ was introduced in 2009, and rolled out in 2010 and was implemented at a far faster pace than in Nigeria. The system leverages biometric information in combination with the harmonisation of previously existing data, and is used to reach marginalized populations as part of social welfare programs. This created a major incentive for the enrollees, as those who sought to receive their welfare disbursements were now required to provide valid identification. The strength of India’s system lies in the country’s ability to leverage technology to track various biometric aspects of user identity, from fingerprint identification to iris scanning.

This provides some flexibility for data capturing, without restricting every single citizen to the same requirements. In 2019, the Identity Management Authority announced that 1.25 billion residents of the country (90% of the total population) had received their national identity card. There are clear lessons to learn from India’s successful implementation which stemmed from a clear understanding of the needs and motivations of their populace, as well as a holistic adoption of technology.

Ghana utilised a vast array of municipalities and district offices to manage its identification onboarding process, allowing it to leverage existing resources and increase its accessibility to more than 25 per cent of its population in under a year.

How can Nigeria capitalise on the learnings from India and Ghana? Can we leverage existing social programs to incentivise uptake like we saw in India or use existing infrastructure and capacity across government agencies and offices like in Ghana? The current pandemic has highlighted the failings in our national identity strategy- and results like never before. Millions of farmers like Oriyomi are stranded and unable to get to the business of feeding the nation and their families.

The power of identity cannot be understated, especially in a country like ours where so many people are vulnerable. Identity management, with its ability to include broad segments of the population, is critical for nation-building, and consequently, the enhancement of socio-economic transformation and growth.

For those at the bottom of the pyramid, with limited access to the necessary collateral to have formed a part of any existing database thus far, the challenge – and the need – is much greater. For basic social service providers to reach these underserved populations, knowing who they are is the critical first step: it affirms their existence, and in so doing, their potential access. For smallholder farmers in particular, who are instrumental to our nation’s food security efforts and ambitions, movement is critical to feeding the populace, which means that their inclusion is critical and deserves immediate action.

Nwuneli is a managing partner at Sahel Consulting.

END

Be the first to comment