Editor’s note: The opinions in this article are the author’s, as published by our content partner, and do not represent the views of MSN or Microsoft.

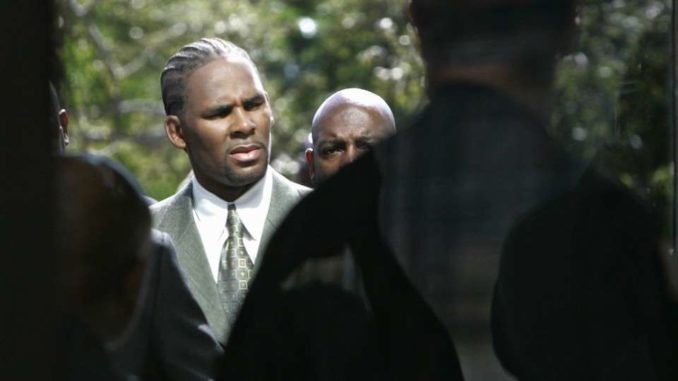

Last week, many viewers watched Surviving R. Kelly in horror as the documentary highlighted old and new sexual-abuse allegations against the singer. The six-part documentary series, which premiered on Lifetime on January 3, featured dozens of testimonials from survivors, activists, police officers, and legal experts, as well as Kelly’s family members and former employees. Their collective accounts paint a picture of a predator of vast proportion and shine a light on the pervasive, insidious culture of sexual violence within the music industry.

Though the exposé has done much to erode the singer’s image (and has spurred an investigation into Kelly by Georgia’s Fulton County district attorney), it has also seemingly bolstered his support. Plays of Kelly’s records spiked on Spotify just after the film aired. And despite the fact that black female activists have successfully campaigned to ban Kelly and his music from several national radio shows and event venues, the artist’s long-standing recording contract with RCA records remains intact. (Kelly has largely denied the allegations against him.)

Further, die-hard fans haven’t skipped a beat in enjoying his music and performances. “I am an R. Kelly fan. I’m here for the music and nothing else,” one woman says in the film. Those who have expressed outrage after seeing Surviving R. Kelly are bewildered about how, despite the preponderance of damning testimonies, Kelly’s support from fans—black fans, in particular—remains largely unscathed.

In the final episode, some of the singer’s black concertgoers are interviewed while lining up for his show. Presumably, they are being asked what they think of the allegations against Kelly, and most offer hollow justifications such as “There are two sides to every story,” “Who are we to judge?” and “He’s been the same for years.” Coming from people who look like they could be the parents of any one of Kelly’s alleged victims, the comments sting. Within them, however, lies a larger issue: Why do sexual predators often get their staunchest support from the very communities they prey on?

In my professorial work on race, masculinity, and rape culture, I explain this problem as racialised rape myths. You may already be familiar with rape myths: narratives about sexual assault that provide false logic about the “nature” of men, women, or sexuality. The idea that women “ask for it,” for example, shifts the blame onto victims, as sexual-assault researchers have noted. And these harmful theories are essential in buttressing a rape culture where sexual assault is more likely to occur and perpetrators are less likely to be held responsible.

Yet in some of the public opinion concerning Kelly’s alleged exploits, these harmful ideas are taken a step further by those who identify reported perpetrators first as belonging to their same racial group. With racialised rape myths, people compound untrue narratives about sexual assault with their own self-interests. For example, some African Americans might think defending Kelly is a way to push back against the history of false rape allegations from white women against black men—allegations that functioned as assaults on black communities, as they were commonly used by whites to justify the lynching of African American men during the Jim Crow era.

But when used in the current-day context of protecting alleged abusers, notions such as They’re just trying to bring a good brother down jeopardise the legitimacy of valid critiques of systemic racial violence and injustice. What’s more, such a conflation ignores that sexual assaults, like nearly all other violent crimes, overwhelmingly happen within a racial group. Kelly’s accusers are almost entirely black: If the criticism of the criminal-justice system is that it is verifiably racist, then wouldn’t that racism also disadvantage black female victims?

Intra-racial sexual-assault cases also tend to shift some black people’s commonly accepted notions about the fairness of the court system. Kelly was fully exonerated of his child-pornography charges, even with the smoking-gun evidence of the grotesque home video in which he allegedly appears. His fans often point to this verdict as proof of his innocence—a surprising about-face for a group that knows intimately the miscarriages of justice in many police-shooting acquittals, for instance. The George Zimmerman not-guilty verdict and the Darren Wilson grand-jury non-indictment did not convince masses of African Americans of Zimmerman’s and Wilson’s respective innocence. They mainly fuelled the protests against what huge swaths of people perceived as gross legal injustices.

This logic-bending as a means to protect black men has an explanation in black feminist theory. In her 1990 book, Yearning: Race, Gender, and Cultural Politics, the scholar bell hooks writes, “Many of us were raised in homes where black mothers excused and explained male anger, irritability, and violence by calling attention to the pressures black men face in a racist society … Assumptions that racism is more oppressive to black men than black women, then and now, are fundamentally based on acceptance of patriarchal notions of masculinity.”

Upholding this idea leads to a culture of shielding black men that consequently injures black women and girls. Common tropes used to excuse predatory behaviour, such as “These little girls are fast,” are victim blaming on the surface but, as sociologists such as Patricia Hill Collins note, are layered with centuries of stereotypes about black-female promiscuity.

In 2005’s Black Sexual Politics, Hill Collins explains that justifying the racial hierarchy in America’s founding required “ideas of pure White womanhood” that could only be created in juxtaposition with sexual stereotypes about Native and African women: “In this context, Black women became icons of hypersexuality.” The legacy of these stereotypes, according to the historian Deborah Gray White, was also used to explain why black women and girls were subject to rape by white men during slavery and Jim Crow.

Racialised rape myths are as universal as rape itself, and they occur within nonblack communities as well. When the former Republican Senate candidate Roy Moore faced several allegations of sexual misconduct with minors, support in the politician’s home state of Alabama remained strong with the majority of white voters (some 63 percent of white women stuck with Moore). Although the record turnout among African Americans would help elect Moore’s Democratic opponent, Doug Jones, many couldn’t understand why Moore’s campaign wasn’t more damaged by the allegations (Jones skated by with only a two-point lead). In one focus group, white voters aligned with Moore mostly absolved him of the allegations, offering defenses such as “Nobody’s perfect” and “Forty years ago in Alabama, people could get married at 13 and 14 years old.”

Similar sentiments are found in the “Boys will be boys” attitudes from some white men and women that cropped up during Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearing. These myths present violence as inherent to masculinity. They also downplay the role of white privilege in the impunity often afforded white men—which in turn benefits white women, whose advantages in the American social hierarchy are derived primarily from race, not gender. “We saw our brothers, husbands, dads, friends, and sons, and we’re determined not to live in a world in which good men are ruined by unsubstantiated allegations,” a female Kavanaugh supporter told The Washington Times. Holding white men accountable with regard to sexual assault would potentially jeopardise white women’s proximity to power.

In Surviving R. Kelly’s opening episode, viewers are reminded of Kelly’s compelling biography: rising from public housing in Chicago to become one of the most famous artists of his generation and an icon of black R&B’s crossover success. For many African Americans, the individual successes of celebrity talents are worn as badges of accomplishment for the race as a whole. When the Grammy Award–winning singer Erykah Badu introduced R. Kelly at the 2015 Soul Train Awards—a show that draws mostly black audiences and celebrates mostly black performers—she lauded him, saying that Kelly “has done more for black people than anyone.” Badu struck at the heart of one of the most injurious racialised rape myths of all: that representing one’s race in the mainstream by achieving individual, odds-defying success absolves people from harm they have perpetrated against other members of the race.

These ideas don’t need to be endorsed by all or even the majority of people within a racial group to be effective rationalisations for excusing sexual violence. They serve a purpose for men who see themselves as competing to achieve a higher social standing and for other men who see themselves as trying to maintain their current social standing. The myths also validate the self-defeating views of women who see their status as primarily linked to their male counterparts, whereby men’s interests and protections stand in for the interests and protections of the race writ large. The survivors in these respective groups, however, continue to suffer the consequences.

END

Be the first to comment