New research presented at this year’s European Congress of Clinical Microbiology & Infectious Diseases (ECCMID) in Amsterdam, Netherlands (April 13-16) showed that the geographical range of vector-borne diseases such as chikungunya, dengue fever, leishmaniasis, and tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is expanding rapidly.

Spurred on by climate change and international travel and trade, vector-borne disease outbreaks are set to increase across much of Europe over the next few decades—and not just in the temperate countries around the Mediterranean.

Even previously unaffected areas in higher latitudes and altitudes, including some parts of northern Europe, could see an increase in outbreaks unless action is taken to improve surveillance and data sharing, and to monitor environmental and climatic precursors to outbreaks, alongside other preventive measures.

“Climate change is not the only or even the main factor driving the increase in vector-borne diseases across Europe, but it is one of many factors alongside globalisation, socioeconomic development, urbanisation, and widespread land-use change which need to be addressed to limit the importation and spread of these diseases”, said Professor Jan Semenza from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, Stockholm, Sweden.

“The stark reality is that longer hot seasons will enlarge the seasonal window for the potential spread of vector-borne diseases and favour larger outbreaks”, said Dr. Giovanni Rezza, Director of the Department of Infectious Diseases at the Istituto Superiore di Sanitá in Rome, Italy. “We must be prepared to deal with these tropical infections. Lessons from recent outbreaks of West Nile virus in North America and chikungunya in the Caribbean and Italy highlight the importance of assessing future vector-borne disease risks and preparing contingencies for future outbreaks.”

However, the authors caution, that given the complicated interplay between multiple drivers (example, warming temperatures and international travel), weather sensitive pathogens, and climate-change adaption, projecting the future burden of disease is difficult.

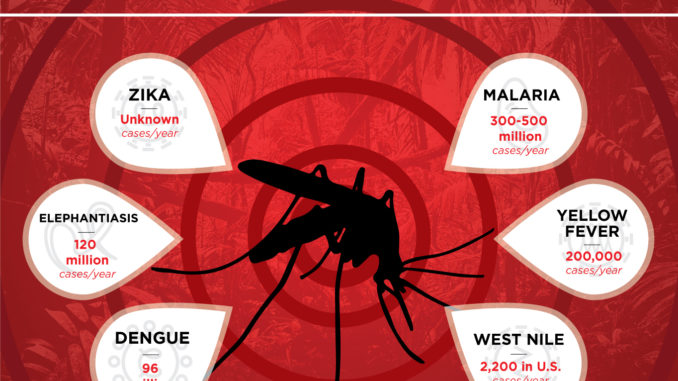

Global warming has allowed mosquitoes, ticks and other disease-carrying insects to proliferate, adapt to different seasons, and invade new territories across Europe over the past decade—with accompanying outbreaks of dengue in France and Croatia, malaria in Greece, West Nile Fever in Southeast Europe, and chikungunya virus in Italy and France.

Worryingly, the authors say, this might only be the tip of the iceberg. “Mediterranean Europe is now a part-time tropical region, where competent vectors like the Tiger mosquito are already established”, said Rezza.

Hotter and wetter weather could provide ideal conditions for the Asian tiger mosquito (Aedes albopictus), which spreads the viruses that cause dengue and chikungunya, to breed and expand across large parts of Europe including the south and east of the United Kingdom (U.K.) and central Europe.

Previously dengue transmission was largely confined to tropical and subtropical regions because freezing temperatures kill the mosquito’s larvae and eggs, but longer hot seasons could enable A. albopictus to survive and spread across much of Europe within decades, researchers say.

The European climate is already suitable for the transmission of Lyme borreliosis and tick-borne encephalitis which are spread by ticks (primarily Ixodes ricinus)—with an estimated 65,000 cases of Lyme borreliosis a year in the European Union, and a 400 per cent rise in reported cases of TBE in European endemic areas over the past 30 years (partly due to enhanced surveillance and diagnosis).

Also, another new research presented at ECCMID identified a novel association between antibiotic resistance and climate change. The study was conducted at the Institute of Infection Control and Infectious Diseases, University Medical Center Göttingen (UMG), Germany, in collaboration with the Hannover Medical School (MHH), Germany. The lead author is Professor Simone Scheithauer of UMG.

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a threat across Europe with burdens mainly peaking around the Mediterranean Basin. Recently, the association of AMR with climate gained increased attention, since resistance increased with increasing local temperatures in the USA.

This new research investigated whether the explanatory strength of climate variables holds true in a region with diverse healthcare systems and societies and whether a climate change dimension can be identified, using Europe as a case region.

The researchers conducted a 30-country observational study across Europe (see below for list of countries). The six-year prevalence of carbapenem resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa (CRPA), Klebsiella pneumoniae (CRKP), multi-resistant Escherichia coli (MREC), and Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) was determined based on data published by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC).

Statistical analysis and computer modelling were performed to identify associations between AMR and seasonal temperature, including potential socioeconomic and health system related confounders. The team found significant associations of CRKP, MREC and MRSA with the warm-season mean temperature, which had a higher contribution to MRSA variance than outpatient antimicrobial drug use.

Furthermore, CRPA was significantly associated with the warm-season change in temperature. The authors also used their models to estimate AMR in four other countries, not included in the database used (Belarus, Serbia, Switzerland and Turkey). The results displayed varying degrees of accuracy compared to empirical data, with comparatively good matches for CRPA in all countries except Belarus.

The authors conclude: “Our study identified a novel association between AMR and climatic factors in Europe. These results reveal two aspects: climatic factors significantly contribute to the prediction of AMR in different types of healthcare systems and societies, while climate change might increase AMR transmission, in particular carbapenem resistance.”

They added: “While these results remain hypothetical as it is unknown if any causal association exists, future analysis of AMR and climatic developments is necessary to determine whether potential climate change effects on AMR become stronger.”

END

Be the first to comment