Èèyàn Ò sunwonláàye

Ijo a baku la n di ere.

Humans are not honoured while alive.

The day one dies is when one becomes a statue.

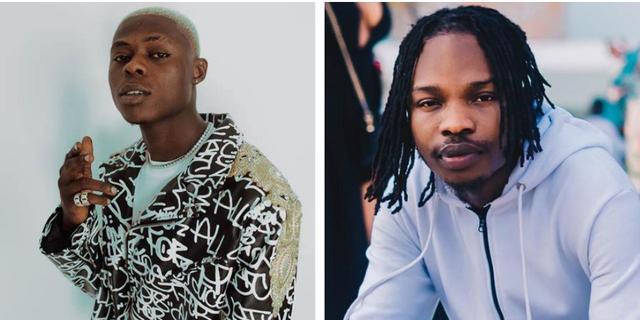

If you are here to read the rumours about the life, times, and death of MohBad, I am sorry to disappoint you. You can go watch some of the numerous skits, blogs, and videos on social media. Dem boku for there! This is not the place for that. The late Promise Irelioluwa Oladimeji Aloba aka MohBad (1996–2023), is dead, and the stories surrounding the circumstances of his death can be found everywhere.

It can be found in the rubbles of his lyrics and music, and it can be found in the tears of his cries for help and his ordeals in the hands of all his handlers, from his parents, immediate families, friends, enemies, his fans, managers, those who hate his lifestyle and music, record labels, the Nigerian Police, the hired thugs, drug dealers, the Nigerian music industry, and the government.

The MohBad to read here is any creative genius that has anything to do with legal contracts, record labels, and laws to protect his, hers, or their intellectual properties. The MohBad that died is merely the messiah, the change agent, and the light (imole) that the Lord has chosen to effect and herald a positive change in the music industry in Nigeria. The MohBad that died is the luminous lamp (imole) and torchlight (imole) chosen to illuminate the opaque, dark, bleak, obscure, occultic, and cultic landscapes and landforms of the Nigerian music, film, and creative industries.

The MohBad that died is the sacrificial lamb whose spilled blood (if properly channeled) may sanitise and purify not only the Nigerian record label industry and the Nigerian music industry but the entire Nigerian creative industries.

The rat race and exploitative relationships between artistes and their agents, managers, and record labels or record companies in Nigeria are not something new. It didn’t start with MohBad and the Marlian Records, and it won’t end with them. It has been like this since the beginning of modern music in Nigeria. The saving grace now is the invention of social media.

At this juncture, it may be appropriate to ask: What is unique and different in this ongoing tragic saga between MohBad and his former record label, Marlian Record? Well, the answers can be found in the misconceptions of the term, record label or record company.

The answers can be found in the rubbles of the changing meanings, forms, roles, and concepts of the term, record label, or record company, particularly in 21st-century Nigeria. The answer can be found in the obsolete policies and lack of guidance by the government, the void filled by sharks and vultures masquerading as entertainment lawyers, and in the lacuna created by recording artistes, professional record labels, and practitioners in the Nigerian music industry.

To simplify the term record label, let’s first understand the meaning of the two words “record” and “label”. A record is any preserved or documented oral or written account, while a label is any sign, symbol, piece of paper, or material that provides information about the object that it is attached to. ‘Record’ is the adjective describing the noun “label”; therefore, a record label can be described as a form of label that records something. It implies a distinguishing emblem that provides information about a record.

The term originates from the paper label glued around the center of a record. However, in business terms, a record label is a business entity or a company whose aim is to preserve, promote, and distribute records on behalf of its artistes.

Its aim is to monetise recorded music and to act as the custodian, adviser, agent, wholesaler, retailer, marketer, financier, producer, and general promoter of an artiste or artistes.

A record label is a service provider with a vested interest in the growth, fame, and financial success of musical artistes and records within its care or custody. Record labels are not charitable organizations. They are not orphanages. They are not correctional service centres. They are not welfare organizations to cater for the artistes and their families. They are business ventures with the sole aim of making profit through the distribution, marketing, and promotion of musical records and artistes. They are neither (public or secret) cult groups nor community or tribal associations.

Prior to the birth of record labels, theaters and churches served as meeting places where people went to listen to music and enjoy general performances. During this period, sheet music was the major means of recording and preserving music. The invention of the piano by Bartolomeo Cristofori (1655–1731) around 1700 increased the popularity of sheet music. However, Thomas Edison’s (1847–1931) invention of the phonograph and Alexander Bell’s (1847–1922) invention of the telephone in the 19th century gave birth to the creation of record labels.

Equally important is the contribution of the Victor Talking Machines Company (1901) in the United States, whose phonographs made it possible to record and duplicate music records at commercial levels. The inventions of radio, television, and other recording instruments and devices in the 19th and 20th centuries provided the platforms for the growth of the record label industry and the music industry in general.

Consequently, six major record label companies emerged during the period: Warner Music Group, EMI, Sony Music, BMG, Universal Music Group, and PolyGram. Due to financial and commercial considerations, some of the six companies merged, leading to the emergence of the Big Four and now the Big Three record label companies, namely Warner, Universal, and Sony. The use of the word “big” to describe these record label companies is due to their structural and financial capacity as well as their control over “more than 5% of the world markets for the sale of records or music videos” (see The Association of Independent Music, https://a2im.org/).

Based on this rule, record labels are divided into major and independent record labels. Independent record labels, or indie labels, do not have the same financial capacity and international influences as the Big Three. However, they have a closer relationship with the artistes, specialized genres, and can be owned by the artists. While independent record labels have no affiliation with the major record labels, there are also record label companies that act as subsidiaries of the major label companies. They are referred to as major label subsidiaries.

The technological advancements of the 21st century are fast changing the landscape of the record label industry. New discoveries on the internet and video-sharing apps have opened more vistas for artistes and made it possible to play more direct roles in the business of record labels. There are now net labels, web labels, digi labels, open-source labels, crowd funded labels, and many imprints. This is perhaps the major contributing factor to the growth of the record label industry in Nigeria.

Prior to these new technologies, the Nigerian record label industry was controlled by major label subsidiaries and independent record labels. Some of these record labels include Knitting Factory Records, African Songs Ltd., EMI Records (now Ivory Records Nigeria), Siky-Oluyole Records, Decca Records, Premier Music, Right Time Records, Olumo Records Limited, Ebenezer Obey Music Company Limited, Ogene(Q)Holdings Ltd., Rogers All Stars, Loveworld Records, and Virgin Records.

To be continued tomorrow

Dr. Otun is of the Department of Comparative Humanities, University of Louisville, Louisville, Kentucky USA.

Be the first to comment