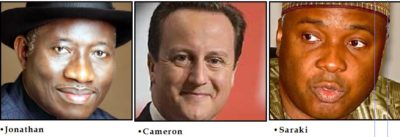

Can you for a moment imagine what Nigeria would be going through now if Dr Goodluck Jonathan had not gone down to defeat in last year’s Presidential election – defeat so heavy that he could not refuse to concede?

For one thing, the massive looting of public resources that we must now regard as a fundamental objective and directive principle of state policy in his time would never have come to light, or would have done so when it no longer mattered. Or again, it would have been portrayed as the contrivance of the usual detractors too far gone in their malevolence or envy to perceive, much less appreciate, the great transformation occurring all round them.

But even his most unyielding detractor will have to concede that Dr Jonathan, whom no one has ever accused of possessing a fine sense of discrimination despite his advanced training in ichthyology, was right on this one. What took place was stealing pure and simple, unworthy of being dignified as corruption, even though in Dr Jonathan’s book, the latter was the greater crime, the former apparently rating no higher than third-degree malfeasance.

Just when you think you have heard the ultimate revelation, the next day brings forth disclosures that make the totality of what had been reported stolen earlier seem benign, almost edifying even. By some conservative reckoning, as much as one half of the GDP may have been stolen during each year Dr Jonathan held office.

But you cannot blame Dr Jonathan for that.

“My approach to corruption,” (read “stealing”) “was don’t make any money available to anyone to touch,” he told Bloomberg TV New York, after a speech at Bloomberg Studios in London and reported in The Guardian (Lagos).

There you have it.

Jonathan fought corruption by simply refusing to make money “available to anyone to touch,” persuaded that if you can’t touch it, you can’t steal it. In the digital age, it is indeed true that a great deal of stealing occurs in cyberspace, with the touch of a button on a computer keypad or the swiping of an electronic card.

But much of the thieving that occurred under Jonathan’s administration was of the old-fashioned kind, like officials presenting handwritten notes at the Central Bank and driving off with billions of dollars stashed in cartons, or having one-half of the payroll for an entire agency delivered to their homes every month for several years, or burying millions of dollars in make-believe septic tanks in their homes.

According to the best authorities, if Dr Jonathan had not pursued the tight-money policy that made money unavailable for touching, Nigeria’s entire GDP, plus some, will have been stolen each year he was in office.

And there would have been nothing left to execute his Transformation Agenda, the fruits of which are all around us, not least the glut in food production and the millions of new farm jobs he talked about in the Bloomberg interview, thanks to the electronic wallet scheme that delivered fertilisers directly to farmers even in the most remote villages, cutting out the massive corruption that had paralysed the distribution chain.

I am in a position to announce that, in the years ahead, Dr Jonathan will be giving the world the benefit of his unique approach to fighting corruption — just don’t make money available for anyone to touch – by way of a Distinguished Lecture Series he has graciously agreed to teach online, under the auspices of The Goodluck Ebele Azikiwe Jonathan School of Public Management and Finance at the Federal University of Otuoke, where he is set to be named the Dame Patience Faka Jonathan Distinguished Professor of Public Service.

Be sure to tell prospective enrollees that you first learned about the programme from this column.

Prime Minster David Cameron must be ruing the day he promised to organise a referendum to determine, once and for all, whether the UK should remain in the European Union or quit. He didn’t do it on a whim; he calculated that a “yes” vote would silence all the sniping on the Tory back bench and unite the party behind him.

In the event, the Brexiteers won a narrow victory – a plurality of less than 2 percent, with 30 million subjects or roughly 70 percent of the population voting. But it is a victory with likely consequences so far-reaching that we can only glimpse their hazy out lines now. It may well go down as the day when everything changed for the residents of those sceptred isles.

A week later, the “United Kingdom” seems anything but united and not much of a kingdom. Those who “won” seem only slightly less confused than those who “lost.” There is no great rejoicing in the streets. It is almost as if the people had sleepwalked through the whole thing

But trust the Brits. They will muddle through this one, as they have always done. It is not for nothing that they invented the science of muddling through.

Every major development elsewhere has a way of turning Nigerians into more than detached observers and leading them to draw parallels with their homeland. The Brexit referendum was no exception.

A Nigerian election or referendum in which winner and loser are separated by less than two percentage points would most certainly have been declared “inconclusive.” Even a poll won by a far higher margin would still have been declared inconclusive if the authorities chose not to proclaim the results. And there would have been no shortage of arguments to support the claim that it was incurably inconclusive.

I am reminded again of the June 12, 1993 presidential election in which the Social Democratic Party (SDP) and the National Republican Convention (NRC) were the contestants. The winner of the poll, so said a front-page editorial in the New Nigerian, the fully-funded official mouthpiece of the Northern Establishment and whichever among its factions was running the country, was Arthur Nzeribe’s misbegotten Association for a Better Nigeria (ABN), which was not even a party to the election.

How so?

Because, said the New Nigerian, ABN’s phantom registered membership of 25 million which had stayed home on Election Day as instructed by Nzeribe, outnumbered almost 2:1 those registered electors who had voted for the SDP and the NRC.

And that was by no means the most trifling argument that led a large swathe of the public to accept that the election was indeed inconclusive.

Finally, at the risk of sounding boorish, I have to ask again whether Senate President Bukola Saraki cares about anybody or anything other than Saraki, and whether he knows the difference between statesmanship and careerism.

That he has been standing trial charged with perjury is scandal enough. Now, based on a police report, he has been charged with complicity in the forgery of documents that created the path through which he and Deputy Senate President Ike Ekweremadu carried out their hostile takeover of the institution.

Saraki is praying the court to stand the letter proceedings down, on the ground that simultaneous prosecution will imperil his right to a fair trial and the performance of his constitutional duties.

Our laws presume .an individual innocent until he or she is proven guilty. But in other climes whose traditions and usages Saraki claims to embrace, that presumption always yields to the far higher principle of noblesse oblige.

Saraki can still earn himself an honourable place in Nigeria’s history by bowing to this hallowed principle instead of clinging desperately to his career – such as it is – through employing the tawdriest contrivances e’er devised by the best lawyers that money can buy.

NATION

END

I SINCERELY AGREE WITH U.CUS SARAKI NEED TO HONOUR AND WRITE A GOOD HISTORY FOR HIMSELF BY STEPING DOWN.