Never forget where you come from. It is something that fighters, in particular, know too well. It is what gives them courage to fight, and it is where they draw strength from in moments of crisis.

Like almost no other sportspeople, a fighter’s background defines them – from Mexicans compelled to live up to their country’s famous traditions, to Gennadiy Golovkin who was marched around war-torn Kazakhstan as a boy by his military brothers to fight fully grown men, to Tyson Fury who has Traveller blood coursing through his veins.

Anthony Joshua is no different. Africa is emblazoned on his bicep and that is why, at his lowest ebb and desperate to seek solace, he journeyed to Nigeria for the first time in 17 years in a spiritual trip that re-lit his fire to regain the world heavyweight championship that was lost to Andy Ruiz Jr.

Makoko is a floating slum in the Lagos lagoon, a city built on stilts but struggling to stay afloat.

It is easily within view of visitors to Lagos but only if you know where to look – the estimated population of up to 300,000 people were not counted in the most recent census, and there is no official record of their existence.

“We went into the back, back, back streets,” Joshua exclusively tells Sky Sports about venturing to Makoko. “They say politicians don’t even go there.”

There have been demolition attempts in 2012 and again in 2016, when an estimated 30,000 were made homeless. But still Makoko will not drown beneath the sludge and slime upon which is it built.

It is a place, for all its difficulties, that puts a wide smile on Joshua’s face at a time when he is being questioned and doubted like never before.

“What’s it like? Ok…

“Nigeria has a massive population – the mega-rich, the poor, and not much in between. Makoko is at the lower end. It is overpopulated.

“The transportation is on boats.”

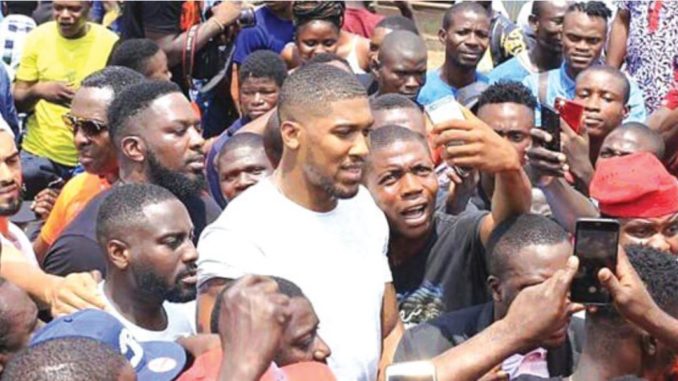

World heavyweight champions arriving unannounced in deprived areas is not new – Muhammad Ali mixed with the impoverished people nearby his Miami training camp and, more recently and closer to home, Mike Tyson popped up in Brixton, south London, where the adoring masses forced him to be rushed into the town hall for safety then evacuated in the back of a police car.

But Joshua’s visit to Makoko was different.

Humbled by a first defeat and the relinquishing of his world titles, he was stripped back to being a young man seeking inspiration.

“People were baffled that we went there,” Joshua smiled. “It is the ghetto. It is quite dangerous.”

There must have been a few ropey moments?

“Kind of.

“Let’s say a space that could hold 500 people had 2,000 people in it. Imagine trying to walk. We were shoulder to shoulder.”

Did they all recognise Joshua as the famous boxer of Nigerian heritage?

“Even if they didn’t know who I was, they understood that there was something happening in the air that they wanted to know about. They didn’t want to let us go.”

There is a reason that privileged people do not ordinarily go to the Makoko slum. But with Joshua? There is mutual respect, a sort of kindred spirit. They sing his name.

“We went to the Fela Kuti Shrine,” he said. “It has become a social club where they can all watch my fights.

“They told me, ‘Make sure you go get those belts back’. That is massively inspiring.

“I could win 10 titles, land at Heathrow, and have nobody waiting for me except for my mum and my cousin. When I landed at the airport there?”

Joshua, the man mountain, briefly has to stop talking and look away.

Anthony Oluwafemi Olaseni Joshua was born in Britain to Nigerian immigrant parents. He spent six months at boarding school in Nigeria when he was 12, but had not returned since, until his visit to the Makoko slum.

His heritage has always been a source of pride and, recently, the green and white of the Nigerian flag has waved alongside the Union Jack behind Joshua as he prepares for battle. He has reconnected to the country of his ancestry and found strength from it.

Has it made his family proud?

“Yes. It is important, really important.

“It’s important for kids to know that they are in a position where they have water, electricity, NHS, education. They have to use that to their advantage.

“What’s their motivation? To buy an iced-out watch? Is that success? That is only feeding into capitalism.

“If you are blessed enough to be from a country that provides these things, you need to think about people who are dying. There are people travelling across seas and deserts to get (to the UK). And the kids already here, instead of creating unity in the community, are stabbing and fighting each other. That is such a shame to see.”

Thinking of the people he met in Nigeria, the message Joshua wanted to get across is this: “I wish anyone reading this who can help would reach out. I just need to know how to help more.”

Joshua gleans desire from other uber-successful people, those who know what it’s like to strive against the odds then face the scrutiny of publicity. Upon his return from Makoko earlier this year he was empowered by Barack Obama, the former president of the United States.

“He is an inspirational man who dealt with a lot of criticism,” Joshua said. “He inherited his presidency at a tough time in America. He dealt with a lot.

“He didn’t put a foot wrong. He’s a married man with kids, and no scandals. He inherited when we were coming out of a global (financial) crisis, and did two terms. He was the first black president and they said he wasn’t even from America – they asked to see his birth certificate. African heritage.

“When I met Obama I asked myself: ‘what type of person do I want to be?’”

“Listening to Obama, you can tell that he is a powerful man but very low-key.”

Joshua’s fire has been re-lit ahead of his rematch on December 7 for the IBF, WBA and WBO titles with Ruiz Jr. When the bell rings and his career and reputation dangle precariously, the lessons learned from the Makoko slum will be where he draws strength from, knowing he is finally fighting for something far bigger.

Courtesy: Skysports

END

Be the first to comment