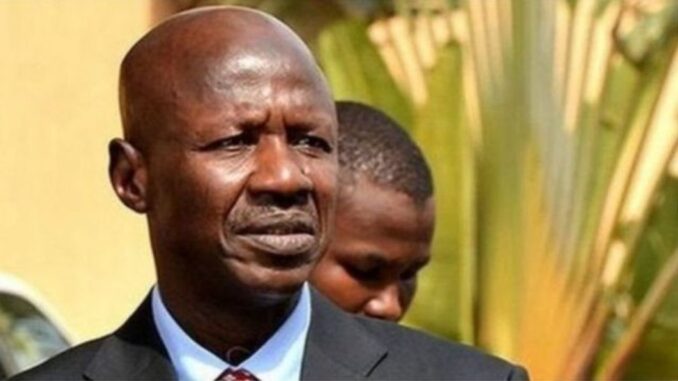

The table turned, as it often does in a world programmed to constantly remind us that the only certainty in the life of man and nations is uncertainty. You should find nothing unusual in Ibrahim Magu, now not respectfully referred to as former chairman of the anti-graft body, EFCC, who, for some five years hunted men and women on whose fingers he suspected smears of palm oil and who, given the colour of ink in their bank accounts had bank managers ministering to their every need, becoming the hunted.

Naturally, there is great rejoicing among the men and women whose fate, until now, was in Magu’s hands. They believe his debacle charts the path to their freedom, the freedom to enjoy their loot at our expense and thumb their noses at those who seek to wear their morality on their sleeves.

But this is a messy situation, not just for Magu, but more importantly for President Muhammadu Buhari, his anti-graft war and the country. However it ends, the president will have a rotten egg on his face; the integrity of the anti-corruption war would sway in the wind of public scepticism; the rest of the world would snicker at the anti-corruption war because if the anti-graft war leader is tainted, the integrity of the war is tainted. Magu would not return and indeed, he might be made to drop his police uniform and head home in a whimper and hang his trophy on his wall as the first anti-graft chief to be so wretchedly defeated by graft; and EFCC as an institution would become one more fine national banner with unsightly stains.

However, I would imagine that the president’s men would be gleeful about citing Magu’s travails as evidence that the anti-graft war is no respecter of persons and that dealing with the former chairman this way amounts to incontrovertible and credible evidence that the president is sincere and committed to the prosecution of the anti-corruption war without let or hindrance. Rationalisation lends itself as a crutch when turning the negative into the positive in this sort of a slippery challenge. So, the president and his anti-graft war win, right? You bet.

Magu stepped into that office in 2016 with question marks on his personal and professional integrity. At his confirmation hearing in the senate, the Directorate of State Security submitted a report on him indicating that given his record of service in the police, the president would do well to look for someone else for that high-profile office. The president, firm in his wisdom that his choice of Magu could not be assailed, twice ignored the senate’s rejection of Magu on the basis of that report. And because the senate refused to confirm him and Buhari would accept no other man, Magu set the record as the longest serving acting chairman of the commission. Now that you-know-what has hit the fan, giving no credit to the president’s rigidity in ignoring all objections to Magu, there is trouble in the political kingdom.

The immediate cause of Magu’s travail is the 12-point allegations levelled against him by Abubakar Malami, attorney-general and minister of justice. They forced the president to act by suspending Magu and investigating the allegations against him. The investigators are still at work but an impatient public baying for the blood of the big man has already found him guilty as charged. If the panel investigating Magu has reasons to believe that even if Magu is not as clean as the whistle, his problem with the attorney-general has less to do with his alleged corruption and more to do with his losing the simmering war of attrition between the two powerful men, he would still be the loser.

I have read the allegations and in my view, they do not amount to a hill of beans. They are, to be charitable, evidence of alleged incompetence on the part of the chairman. More ominously, they point to a dirty power play among the president’s men. This is common in every government; some lose and some survive in a better shape. I am sure a similar thing is going on among the president’s men too in the ministries and parastatals. Power play is inevitable but if it is not properly handled, it could make an administration dysfunctional.

If you discount the first two allegations by the AGF, to wit, “alleged discrepancies in the reconciliation records of the EFCC and the Federal Ministry of Finance on recovered funds (and) declaration of N539 billion as recovered funds, instead of N504 billion earlier claimed,” you would see that there is nothing really that serious in the allegations to warrant the man’s wretched humiliation in the manner that seriously calls the integrity of the institution he headed into question.

Magu has put out a stout defence of the allegations by the AGF but no matter how strongly he may protest his innocence, he has lost his office because he has lost out in the power play between him and Malami. Most of the allegations against him, such as insubordination, could have been sorted out administratively with a query. But Malami wanted a pound of flesh. This, then, is not about protecting the institution or enhancing the anti-graft war; it is about the acting chairman who did not feel himself beholden to the AGF as his boss from whom he must take daily instructions in how to do his work.

The tone of the allegations by the AGF suggests that his problems with Magu must have its genesis in his assuming the right to dictate to the former acting chairman. For instance, he accused him of “insubordination to the office of the AGF.” Insubordination is not a crime and in the civil service, it is usually resolved through a query and apology. I chuckled when I read Malami’s allegation that Magu did not respect “court order to unfreeze a N7 billion judgement…” Does the AGF have interest in the case or is he trying to enforce the rule of law? As President Obasanjo would say, I dey laugh o. I recall that at his senate confirmation hearing, the AGF said he reserved the right to pick and choose which court orders to obey or ignore. In a serious nation, that should have denied him his return to his exalted office because no attorney general has that right or liberty.

Perhaps, it is time for the government to pause and re-examine how the anti-graft war has been prosecuted and see if a change in tactics would not give us better results such that our country would earn an acceptably lower score in the annual report of Transparency International. The anti-graft war was intended to clean up the murky image our country acquired over the years and set the nation on the path of probity, integrity and honour at home and in the comity of nation. It was never intended, I would like to believe, to make that image murkier and make our country and its citizens give off offensive smells associated with Ajegunle gutters.

This now seems to be the objective of the war, hence the bells and whistles in its prosecution. The louder the anti-graft war rages, the higher the index of corruption cases rises. It suggests that while it is important for the commanders and the foot soldiers in the war to receive constant public applause, that alone is not evidence that the commission is winning the war. The zealousness in the prosecution of the war has left all our public institutions and our public officers badly tainted. The midnight raid on our senior judges and justices still leaves ashes in our mouths. All our public officers are ab initio, to be lawyerly for a change, guilty of corruption until each can prove otherwise. This was how Buhari fought the war as military head of state.

If the bells and whistles approach is less than stellar, then something has to give. Whatever the president chooses to do or not do, my plea is that he should protect the integrity of EFCC by resisting the temptation to disgrace its chairman out of office. If the integrity of the commission is destroyed, the anti-graft war would, to use my favourite expression, blow in the wind. And one legacy for which he has staked his honour and integrity would elude him.

END

Be the first to comment