In our series of letters from African journalists, film-maker and columnist Farai Sevenzo considers whether the best way to empower women could be to let them make their own decisions about their bodies.

Zimbabwe’s President Robert Mugabe recently left the stage as chairman of the African Union (AU) to a standing ovation from his fellow heads of state.

For nearly an hour he had railed against the lack of UN Security Council reform to allow African representation.

He then discussed the key theme of the summit: “Women’s Empowerment and Development towards Agenda 2063.”

Agenda 2063 is the African Union’s 50-year plan to keep on track the most significant development aims for a fast changing continent, to be reviewed when the AU turns 100, in 2063.

President Mugabe went on to give a history lesson in his own inimitable style.

“Who can ever forget the indomitable and fighting spirit of such legends as Yaa Asantewaa, Queen Mother of the Asante Kingdom? Who, when confronted by the British and British imperialism said to her people: ‘If you men of Asante will not go forward then we will. I shall call upon my fellow women and we will fight the white man. We will fight until the last of us falls in the battlefield,'” he said.

And the 91 year-old observed: “That must have put us to shame, we men. We men are not women. Is there a man who can say: ‘I’m not born of a woman?’ No. They are a special breed, these people.”

Quoting the events of 1900 in Ghana is all well and good, as is pining for his own mother, and he will find more fighting African women in the history books – even his former Vice-President Joice Mujuru, whom he sacked in 2014 after accusing her of plotting to oust him, would be in these pages.

But where will the issue of women’s empowerment be, come 2063?

Africa has been grappling with gender equality since our nations came into being, yet it is plain to see that the corridors of executive power within the UN, AU and African boardrooms have been steadily filling up with women. The optimists among us would see this as miraculous and encouraging, compared to, for instance, some places in the Middle East.

Before we reel off the numbers of female African presidents and women chief executive officers in African business, we should remember that the lot of ordinary women in the farming fields and in market places, in townships and villages, in churches and in mosques, is still deeply aligned to a kind of ancient African patriarchal conservatism which perpetuates their powerlessness and binds them to the will of men.

“Men in general tend not to vomit every morning during their wives’ pregnancy; they do not miscarry and decisions over abortions do not affect their lives, their mental state or their bodies in the same way”

Last December the Sierra Leonean parliament largely agreed to amend their colonial Offences against the Person Act of 1861, which prohibited abortion.

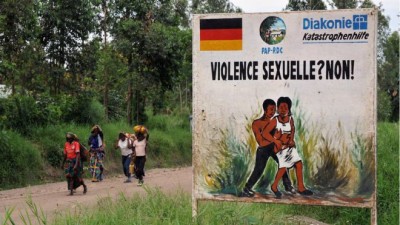

Sierra Leone has the highest maternal mortality rates in Africa and increasing cases of rape, incest and sexual violence against women and young girls have seen illegal abortions rise, along with the tragic consequences of more deaths.

There are over six million illegal and unsafe abortions conducted in Africa every year, according to the World Health Organization. The African Commission on Human and People’s Rights recently launched a campaign to decriminalise abortion across the continent.

We learn that the Sierra Leone health system is straining under the financial weight of corrective obstetrician surgery, which often comes too late to save women’s lives after botched and unprofessional procedures.

When ruling party lawmaker Isatu Kabia tabled the Safe Abortion Act 2015 in the capital, Freetown, last December, it was hoped this might open a new chapter in women’s health and rights.

However, representatives of the Inter Religious Council of Sierra Leone, a powerful body representing faith and conservative morality, had grave doubts and told President Ernest Bai Koroma that they were strongly opposed to such a bill.

Mr Koroma then sent the bill back to parliament without signing it, urging his lawmakers to take another look. The Sierra Leone parliament should be commended for passing the bill in the first place given its gender balance – 106 men and 15 women make up its lawmakers – but will they support it now that the men of faith have objected and the president is wavering?

Now where, you may wonder, were the ordinary views of a “special breed of people” with wombs in all this?

Conservatism in women’s rights seems forever rooted in the views of men. Such views are given prominence by religions and traditions whose leaders are either committed celibates or patriarchal polygamists, and there does not yet appear to be a middle road.

When a new child is expected, there is a tendency in the modern age for some men to say: “My wife and I are pregnant” when it is plain to see that they’re not and cannot be pregnant.

Men in general tend not to vomit every morning during their wives’ pregnancy; they do not miscarry and decisions over abortions do not affect their lives, their mental state or their bodies in the same way.

On this, Mr Mugabe got it right – “We men are not women”. The sooner we leave women’s issues of such a personal nature in the hands of those in the know, the quicker women’s empowerment can come about.

Be the first to comment