EVEN before I had sat in the same classroom with Professor Biodun Jeyifo (BJ to his legion of friends and admirers), I regarded him as my teacher. He had been instrumental to my arrival at Cornell in 2001 to fulfil my long-nourished dream of taking a degree in literature-in-English. With a background in law, my best bet was to apply for a Master of Fine Art in poetry, having already published a collection of poems, finished the first draft of another, and freshly become a fellow of the Iowa International Writing Programme. All I needed were excellent letters of recommendation and statement of purpose.

BJ revised my draft statement into a document sure to be noticed among the mountain of entries, followed by an enthusiastic letter of recommendation. Boosted by an equally hearty recommendation from one Wole Soyinka (you know him?), he opened the road to my pursuit of post-graduate studies, starting with an MFA and ending with a Ph.D in literary and cultural studies that culminated in a dissertation published in 2013 by Palgrave Macmillan as History, Trauma, and Healing in Postcolonial Narratives: Reconstructing Identities.

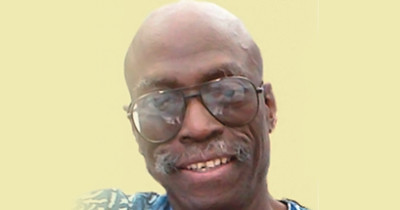

When BJ turned 60,I became his student in the strict sense by enrolling in his seminar “Broken English: English Studies in Post colonial, Post modern Frame,” just before Harvard lured him away. I paid tribute to this exemplary man with a narrative essay entitled “For BJ at 60: A Student’s Random Recollections in Lieu of a Tribute” (West Africa Review, http://www.africaknowledgeproject.org/index.php/war/article/view/275). I would like to add one more word of homage, the man being so accomplished his praise song must be long.

BJ’s name spells R-I-G-O-U-R and E-R-U-D-I-T-I-O-N, as Aretha Franklin had us spell R-E-S-P-E-C-T. His vast body of scholarly articles, books, monographs, edited volumes, and journalistic essays, attest to this universally acknowledged fact among his peers and students. If in doubt, see Wole Soyinka: Poetics, Politics, and Postcolonialism (Cambridge University Press, 2004), his acclaimed study of Soyinka’s oeuvre, a task I need tell you is not for the intellectual feather-weight or faint-hearted! During the two-day conference last week at the Obafemi Awolowo University—where he taught for 11 years before the desecration of our universities led him to the United States in search of intellectual succour for “two years in the first instance”—this reputation set the stage for proceedings.

To BJ, no human problem is quite as simple as it may appear. Thus, we must always probe beneath the surface of ideas and things to apprehend their truer meanings. An ideological task that requires mental agility served by erudition and a constant scrutiny of extant knowledge. In short, epistemological vigilance, intellectual inquiry being a complex matter ab initio: for you see, O le gaani o! The Yoruba rendering summed up the testimony of Tejumola Olaniyan, a distinguished ex-student of BJ’s at Ife and Cornell and now the Louise Durham Mead Professor of English, University of Wisconsin-Madison. There is an American version of BJ’s motto of mental sophistication. After several meetings at which the reading list grew successively longer and the angles of inquiry ever more abstruse, an African-American doctoral student of his exclaimed, “Ah, that brother is tough!”

And now my own testimony. As chair (later co-chair on leaving for Harvard) of my dissertation committee, BJ posed the toughest question at my candidacy exam. I had proposed the theoretical framework of post-positivist realism developed as a counterweight to the growing insidiousness of post-structuralism/post-modernism in the humanities by a community of scholars in which he was active. Naturally, there remained several questions to be answered by this theory. Sensing that I had addressed myself insufficiently to complexity, he asked, “So, Ogaga, how would your framework respond to (primary) texts that are resistant to realist readings?”

O le gaani o! His “unfriendly” question was, however, a major impetus towards the integration of a psychoanalytical approach into my post-positivist realist paradigm.

It led me to recall Frantz Fanon’s famous prescription in Black Skin, White Masks that “only a psychoanalytical interpretation of the black problem can lay bare the anomalies of affect that are responsible for the structure of the complex.” Fanon and Freud would be, then, my guides in grappling with texts that resist realist or simple readings. For if colonialism was nothing but a historical catastrophe, could it have inflicted only material damage and spared the psyche of the colonised? What, then, would it mean to read postcolonial narratives under the prism of trauma? A hard taskmaster had led me to derive new insights into the postcolonial predicament.

That is the teacher and scholar. There is also BJ theunrepentant Marxist and humanist every reader of his newspaper contributions towards progressive change knows.

What many might not know is that 40 years ago, he resigned from the University of Ibadan and withdrew with a few comrades to a commune in Ode Omu, Osun State, to prepare for a socialist revolution. It was after the dissolution of the commune a year after that BJ returned to academia. At 70, his passion for change burns at even greater wattage than his commune days, though perhaps without the same zealfor revolutionary vanguardism. He will soon be back for good from his long sojourn abroad, he announced at Ife last week. All of progressive Nigeria should be counting the days to this homecoming. I wish my teacher and mentor many more fruitful years in health and happiness.

VANGUARD

END

Be the first to comment