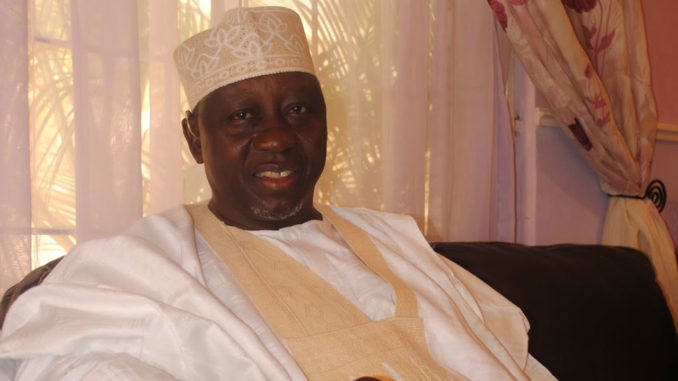

As Lassa fever scourge continues to rear its ugly head in the country, it is important to follow the exemplary attitude of Governor Tanko Al-Makura of Nasarawa State who was once afflicted but has turned the health challenge into an opportunity to deal decisively with the uncommon nut avoidable disease.

The annual resurgence of Lassa fever in the country should be a major source of worry; and should be treated as an emergency, particularly as it is spreading, to avoid needless morbidity and mortality in Nigeria.Lassa fever is an acute febrile illness, with bleeding and death in severe cases. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), it is an acute viral haemorrhagic illness of 21 days duration that occurs in West Africa. Descriptions of the disease date from the 1950s, but the virus was first described in 1969 from a case in the town Lassa, in Borno State, Nigeria. The virus is zoonotic, or animal-borne. Again, WHO states that the reservoir or host of the Lassa virus is the “multimammate rat” called mastomys natalensis, which has many breasts and lives in the bush and around residential areas. So, it is mostly spread by rats!

The virus is shed in the urine and faeces of the rats hence can be transmitted to humans via direct contact, touching objects or eating food contaminated with these materials or through cuts or sores. Person-to-person infections and laboratory transmission can also occur, particularly in hospitals lacking adequate infection prevention and control measures. Persons at greatest risk are those living in rural areas where mastomys are usually found, especially in communities with poor sanitation or crowded living conditions.

About 80 per cent of human infections are without symptoms; the remaining cases have severe multiple organ disease, where the virus affects several organs in the body, such as the liver, spleen and kidneys. According to the WHO, the onset of the disease, when it is symptomatic, is usually gradual, starting with fever, general weakness, muscle and joint pains, prostration and malaise. After a few days, headache, sore throat, muscle pain, chest pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, cough, and abdominal pain may follow. In severe cases facial swelling, fluid in the lung cavity, bleeding from the mouth, nose, vagina or gastrointestinal tract and low blood pressure may develop. Shock, seizures, tremor, disorientation, and coma may be seen in the later stages.

Lassa fever is known to be endemic in Benin, Ghana, Guinea, Liberia, Mali, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, but probably exists in other West African countries as well. While Benin, Burkina Faso, Sierra Leone, and Togo experienced outbreaks in 2017, that have since been controlled; Nigeria is still one of several West African countries in which Lassa fever is endemic, with seasonal outbreaks occurring annually between December and June.

In 2016, the country reported 273 suspected cases and 149 deaths (case fatality rate 55 per cent) from 23 states. According to Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC), during the 2017 outbreak, nineteen (19) States (Ogun, Bauchi, Plateau, Ebonyi, Ondo, Edo, Taraba, Nasarawa, Rivers, Kaduna, Gombe, Cross-River, Borno, Kano, Kogi, Enugu, Anambra, Lagos and Kwara) reported at least one confirmed case.

As at November 2017, the outbreak was active in five states – Ondo, Edo, Plateau Bauchi and Kaduna. Again, on January 14, 2018, four cases of Lassa fever among health care workers in Ebonyi State were reported at the NCDC. Three of the four cases – two medical doctors and a nurse subsequently passed away, despite efforts to save their lives. According to the University Graduates of Nursing Science Association (UGONSA), more than 40 health workers died as a result of Lassa fever in Ebonyi alone in the past 13 years. As at March, 2018, the NCDC said that Lassa fever had claimed 43 lives in Nigeria with a total of 615 cases reported across 17 states.

Currently, the latest National Centre for Diseases Control (NCDC) Situation Report (SitRep) released on January 20, reveal that from January 1 to 20, 2019, a total of 377 suspected cases of Lassa fever had been reported from nine states. Of these, 136 were confirmed positive and 240 negative; and since the onset of the 2019 outbreak, there have been 31 deaths. As at the time of the SitRep, 81 patients were being managed – Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital (ISTH) treatment Centre, 30; and Federal Medical Centres in Owo, Bauchi, Plateau, Taraba, and Ebonyi States are managing 25, 9, 8, 3 and 6 respectively.

So, it is obvious that Lassa fever has become a recurring decimal in the Nigerian health ‘scene’, and in some cases, affected several persons in families across class. Drawing from the statement of the Governor of Nasarawa State, Umaru Tanko Al-Makura, at the first international conference on Lassa fever; the disease, which he contracted in 1990, made him deaf for 20 years before he had a cochlear implant. He also revealed that he lost his first son to Lassa fever nine years after marriage, the second son survived but with the burden of the side effects of the virus, neurological problems, especially hearing loss.

Obviously, Lassa fever is a health deficit in Nigeria that cuts across class, which requires practical and strategic credits to nil the account! Attempts at containing Lassa fever have thrown up different issues just as viral diseases have different strains. Some of the issues range from poor access to preventive care and management, to prohibitive cost of treatment engendering high morbidity and mortality. According to experts, the high cost of managing Lassa fever, as well as, late presentation, slow identification and poor management of cases, range top among reasons for the morbidity and mortality rates recorded over the years.

Practically, the Lassa fever national multi-partner, multi-agency Technical Working Group (TWG) continues to coordinate response activities at all levels; as such the current reported cases do not call for panic as early supportive care are already being given to 81 patients, who are being managed at different health facilities.

Notwithstanding, the affected State Ministries of Health and the Federal Ministry of Health, while responding to contain the current Lassa fever outbreak should not rest on their oars. They should continue to mobilise human and material resources to trace the sources and extent of the disease, follow up on potential contacts, identify early and test suspected cases, since it is a known fact that the annual outbreak occurs between January and June.

Furthermore, although the treatment of Lassa fever is expensive, as it costs at least N500,000 to treat a patient of Lassa fever with the drug-of-choice, Ribavirin, the NCDC should ensure that every state in Nigeria has an emergency stock of Ribavirin and other response commodities available to manage cases to avoid needless loss of lives. Strategically, since there is currently no vaccine that protects against Lassa fever, containing Lassa fever lies in prevention.

The prevention of Lassa fever relies on scientific interventions; and societal and individual behavioural change hinged on good hygiene practices that will prevent rodents from entering homes. Individuals should adopt preventive practices by storing grain and other foodstuffs in rodent-proof containers, disposing of garbage far from the home and maintaining clean households.

While Lassa fever endemic states should rise up to the occasion and follow the footstep of Al-Makura, who is building a comprehensive diagnostic centre in Lafia, in the attempt to eradicate Lassa fever and other infectious diseases; existing centres such as the South-East virology centre built by Ebonyi Government three years ago should be made to function maximally.

END

Be the first to comment