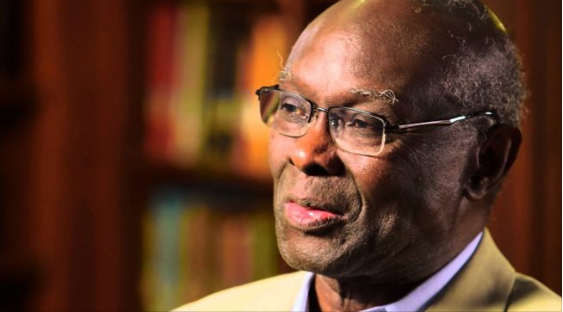

Lamin Sanneh (1942-2019), a foremost African theologian of our time from Gambia in West Africa, was called to great beyond on January 6, 2019, the Feast of Epiphany of our Lord Jesus Christ to the gentile world. Sanneh suffered a stroke and died at the age of 76, in his place of abode, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut in the United States of America. Until his sudden demise last January, Professor Lamin Sanneh was the D. Willis James Professor of Missions and World Christianity at Yale Divinity School and Professor of History at Yale University. Sanneh is internationally, respected and acknowledged as the world’s foremost theologian of World Christianity and Islam.

He was also a co-founder and joint convener of the Yale – Edinburgh Group on the History of Missions and World Christianity. The Group’s annual Conferences, meeting in Yale and Edinburgh alternately, have been an input feature of the academic contribution of this illustrious son of Africa to the world. And as one of the tributes in his honor rightly notes, “the title of Professor Sanneh’s autobiography (“Summoned from the Margin: Homecoming of an African” (2012), appropriately states, Sanneh’s felt “summoned from the margins” in a small island on the Gambian River in West Africa.” From his Gambian environment in Africa, Sanneh was transformed by his Christian faith, embarked upon a distinguished career in the academy, and leaving behind an extraordinary scholarly legacy.

Professor Sanneh also taught at the University of Ghana, Accra, where an Institute, “Sanneh Institute” was established last year in recognition of his illustrious academic career and strive to continue his mission of offering scholarship as a tribute to God with the other within hearing distance. John Azumah, professor of World Christianity and Islam, Colombia Theological Seminary, and director of the Sanneh Institute at the University of Ghana in Accra, shared the following words from Sanneh’s last but one email to him, days before his sudden death last January:

“When I was thwarted in my wish to study theology and be ordained, I went through a terrible period of confusion and doubt. It was like a sickness in which I wondered whether God really wanted me. I started to emerge out of that hole when I saw that I could offer my training and scholarship as a small tribute to the God of Jesus, with Muslims within hearing distance.

Call it a sense of vocation if you like, but I was determined to do the best I could to appeal to Muslims not to dismiss Christians when they give evidence that following Jesus does not mean speaking or thinking ill of others. The resulting proximity should make Christ less a stranger to all of us when his spirit moves in our midst.”

Professor Lamin Sanneh was supposed to present his keynote paper “Themes in Reconciliation and harmony with Reference to Contemporary Africa” at the International Harmony Conference organized by Bishop Prof. Dennis T.W. Ng in Colombo, Sri Lanka, on 7 January 2019. It turns out to be his last paper and was read out at the conference after a moment of silence and prayer.

Tributes have been coming from far-and-wide since the sad news of the demise of this great son of Africa, Professor Lamin Sanneh. Many professional associations, academic institutions, research institutes, libraries, editors of Journals and international Newspapers like New York Times and Washington Post, as well as professionals of all classes have all published in their platforms, tributes of landmarks in honor of this great African scholar of our time. These are colleagues and groups, Professor Lamin Sanneh had in one way or the other interacted with and influenced positively while with us in this mortal world.

As expected, most of these tributes in honor of Professor Sanneh highlighted his contribution to dialogue between World Christianity and Islam, an area he had dedicated much of his life and publication since his conversion from Islam to Christianity as young adult, and all through his university teaching profession.

However, the purpose of our present tribute is to highlight the African dimension of Professor Lamin Sanneh’s writings and theological thought. Although, he worked at the limelight of international stage in the world of academia, Professor Lamin Sanneh had always written and lectured from an African perspective and context. Africa remained the animating spirit and goal of his theological writings and engagements from time immemorial till death snatched him away from us last January.

Who is Professor Lamin Sanneh?

Professor Lamin Sanneh was born and raised in Jinjanburch, Gambia (West Africa). He descended from the nyanchos, an ancient African royal line. His earliest studies in Gambia were with fellow chiefs’ sons. He was born into and raised in an orthodox Muslim family and grew up practicing Islam as his religion. However, as divine providence would have it, he converted later in life to Christianity. He became first a member of the Methodist Church and later moved into the Catholic Church, where he remained a practicing member until his demise on January 6, 2019.

Lamin Sanneh was married to Sandra Sanneh, who is a Professor of isiZulu at Yale University. They are blessed with a son, Kelefa Sanneh, who writes about culture for “The New Yorker”, and a daughter, Sia Sanneh, who was a Research Scholar in Law, Senior Liman Fellow in Residence, and lecturer in Law at Yale Law School.

Professor Lamin Sanneh was educated in four continents, namely, Africa, America, Asia and Europe. He studied precisely in Gambia his native land, University of Birmingham, The Near East School of Theology, Beirut and University of London.

He went to the United States on a U.S. government scholarship to read history. After graduating, he spent many years studying classical Arabic and Islam, including a stint in the Middle East, and working with churches in Africa and international organizations concerned with inter-faith and cross-cultural issues. He studied classical Arabic and Islam for his M.A. and subsequently received his Ph.D. in African Islamic history at the University of London.

A seasoned scholar, highly busy and committed Professor, Lamin Sanneh was Honorary Research Professor in the School of Oriental Studies, University of London, and a life member of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. He was Chairman of Yale’s Council on African Studies. He was an editor-at-large of the ecumenical weekly “The Christian Century” and a contributing editor of the “International Bulletin of Missionary Research.” He served on the editorial boards of several academic journals and encyclopedias, and was a consultant to the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Professor Lamin Sanneh is listed in “Who’s Who in America.” He was an official consultant at the 1998 Lambeth Conference in London and was a member of the Council of 100 Leaders of the World Economic Forum. In 2004, Pope John Paul II appointed him to the Pontifical Commission for the Historical Sciences, and Pope Benedict XVI appointed him to the Pontifical Commission on Religious Relations with Muslims.

He had received an award as the John W. Kluge Chair in the Cultures and Societies of the South by the Library of Congress. For his academic work, he was made Commandeur de l’Ordre National du Lion, Senegal’s highest national honor, and is a recipient of an honorary doctorate from the University of Edinburgh, Scotland. His other academic awards include: Carneige Trust of the University of Scotland, 1980 and the Pew Scholars Program, University of Notre Dame, 1993.

As a professor, Lamin Sanneh had taught and worked at the University of Ghana, the University of Aberdeen in Scotland, eight years in Harvard University and since 1989 took the position of the D. Willis James Professor of Missions and World Christianity, Professor of History and, also Chair of Yale Council on African Studies at Yale University.

According to the Yale University website, “He was an Honorary Research Professor at the School of Oriental and African Studies in the University of London, and a life member of Clare Hall, Cambridge University. He served on the board of Ethics and Public Policy at Harvard University, and Birmingham Civil Rights Institute in Birmingham, Alabama.”

Professor Lamin Sanneh had delivered a series of lectures in different parts of the world. In fact, Joel A. Carpenter on pages 25-26 of International Bulletin of Missionary Research, vol. 37, no. 1 of January 2013, described him as “one of the most original and influential Christian thinkers of our time … whose “intellectual biography is thus one long tale of his finding occasions to look across the grain of conventional wisdom and come to conclusions. He has enjoyed the combined gifts of a relentless critical curiosity and a very different cultural vantage point from that of most Western scholars. Those gifts prompt him to see things that others do not.”

In all his writings, lectures and inter-personal and communal encounters, Professor Sanneh always brought with him his magnanimous spirit. What is most evident in such encounters is his great contagious humanity, humility and friendship. This is most apparent in all his works and writings, which he always did from an African perspective on the North-South global dialogue. He proved himself really, an authentic ‘African ambassador’ in the world of academia and theological studies.

Lamin Sanneh was the author of several books and over a hundred articles on religious and historical subjects. He wrote mainly on the relationship between Islam and Christianity and the study of World Christianity as well as Missions. His books include, “Encountering the West: Christianity and the Global Cultural Process: The African Dimension” (1990); The Jakhanke Muslim Clerics: A Religious and Historical Study of Islam in Senegambia (c. 1250-1905)”, (1990); “Religion and the Variety of Culture: A Study in Origin and Practice” (1996); “Piety and Power: Muslims and Christians in West Africa” (1996); “The Changing Face of Christianity: Africa, the West, and the World (co-edited with Joel A. Carpenter”, (2005); “Disciples of All Nations: Pillars of World Christianity” (2008).

Among his first works I read and which made me fall in love with his writings include, his Magnus opus, “Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture” (1989/2009); and his, “Whose Religion Is Christianity? The Gospel Beyond the West” (2003).

Finally, I was glad to read his masterpiece autobiography, “Summoned from the Margin: Homecoming of An African” (2012). It was a parting gift of this great African scholar to the world. There are other countless works of his, too numerous to mention here, all bordering on his favorite subjects, World Christianity, Islam, History and Missions, all of which he discussed always from an African perspective for cross-cultural encounters and inter-faith dialogue.

My first contact with Professor Lamin Sanneh was through his writings. Before then, however, we have admired each other’s academic commitment of African scholarship from long distance. He later invited me to the Yale Divinity School to participate as a resource scholar for that year’s annual “Yale-Edinburgh Conference”, which he organized together with Professor Andrew F. Walls of the Edinburgh University. However, because of pressing academic loads at the time, I could not honor this last professional invitation from Professor Sanneh at the Yale University. He was gracious enough to understand.

Professor Lamin Sanneh had been a great source of inspiration and model scholar to many young African theologians and beyond. My consolation here is that through my suggestion and under my direction, one of my students in Rome, in 2017, wrote his doctoral dissertation on the thoughts of Lamin Sanneh on the theme of “transcultural and translatability of the Gospel in missions.” Again, Sanneh’s life experience, his religious and conversion journey from Islam to Christianity, and from one Christian denomination to the other, had singled him out as a unique figure and man of rare faith.

Sanneh’s Theological Thoughts from an African Perspective

Lamin Sanneh was born, brought-up and studied earlier in life as a Muslim in his native Gambia in West Africa, and from there, converted to Christianity. In Christianity, he was first a Methodist before becoming a Catholic. He studied in four continents and specialized in many fields of studies. He also travelled wide, spoke many languages and interacted with different cultures.

All these experiences put together helped to shape his theological perspective. His theological perspective, reflected in his writings, covers two major areas, namely, the relationship between Christianity and Islam, and the study of World Christianity and Missions. He wrote always from an African perspective, highlighting the place of Africa in the emerging world Christianity and in the increasingly globalizing world.

In this way, Western scholars and Asians as well, were able to identify easily with his writings and recognize him as a theologian of class of all seasons. This is the most distinguishing aspect of him in comparison with some other African theologians that have remained at the level of critical analysis of the activities of the past colonial Christianity in the continent. Professor Sanneh wrote for post-colonial and post-modernity Africa.

In addition, he had an ecumenical and interreligious theological perspective. He was an ardent apostle and advocate for the timely acceptance of cultural plurality. He maintained that cultural plurality is a fact of historical and religious experience of humanity. God created people differently in many ways and as such gave room for cultural plurality. He held strongly that the incarnation is a defining event in human history that showcased the importance of culture in the lives of peoples. He was an advocate of “mutual respect, mutual understanding and co-operative existence between adherents of different religions of the world because all believe and call on the same God who is Creator of all.”

However, Lamin Sanneh’s writings were all African contextualized and homemade, even though, during most of his adult life, he operated from North America and Europe. His writings portray the effort of an African theologian who wanted to show how the two religions, Christianity and Islam, could live side-by-side with the religious traditions and cultures of African people, in spirit of dialogue, respect, mutual enrichment, encounter and tolerance.

He wrote extensively about the translatability of the Gospel into African culture. Sanneh contends that the translatability of the Gospel into local cultures, different contexts and languages, is something very unique to Christianity, among the other world religions. This can’t be found in Islam since only in Arabic it was believed, Allah spoke to Mohammed. Therefore, translations of Quran into other languages and cultures, is considered anachronistic in Islam.

Sanneh used this argument to explain why Christianity made more inroads in those places in Africa where traditional religion was strongest but very little progress where Islam had been planted during the Arab invasions of the continent:

“Africans best responded to Christianity where the indigenous religions were strongest, not weakest, suggesting a degree of indigenous compatibility with the gospel, and an implicit conflict with colonial priorities… Muslim expansion and growth, which occurred, were most impressive in areas where the indigenous religions, particularly as organized cults, had been vanquished or else subjugated, and where local populations had either lost or vaguely remembered their name for God. For this reason colonialism as a secularizing force helped to advance Muslim gains in Africa. The end of colonial rule inhibited the expansion of Islam in Africa, whereas the opposite seems to have happened with Christianity.” (Lamin Sanneh’s “Whose Religion Is Christianity: The Gospel beyond the West” (2003, 18-19).

Speaking further on the importance of African local languages in spreading the Gospel, he writes that:

“Christianity has felt so congenial in English, Italian, German, French, Spanish, Russian, and so on, that we forget it wasn’t always so, or we inexcusably deny that the religion might feel equally congenial in other languages, such as Amharic, Geez, Arabic, Coptic, Tamil, Korean, Chinese, Swahili, Shona, Twi, Igbo, Wolof, Yoruba, and Zulu. Our cultural chauvinism makes us overlook Christianity’s vernacular character.” (Lamin Sanneh’s “Whose Religion Is Christianity” (2003, 105). See also chapter three of his “Translating the Message: The Missionary Impact on Culture” (1989).

Furthermore, Professor Sanneh advances the argument of the significance of Africa of the new southward shift in Christian landscape. In this context, he argues that the significance of Africa of the new southward “shift” must be located within the global transformation of the Christian landscape by the new centers of Christianity in the southern continents. He adds that the growth of Christianity in the southern continents does not mean a displacement of the “old centers” of the faith. It does not also mean a redefinition of the missionary concept or goal. Rather it is a confirmation of the history of Christian mission that faith travels through the missionary movement of believing community:

“When the Christian faith first traveled from Jerusalem to Athens, North Africa and then to Rome, none of the previous centers was displaced by the new ones. And none of the new centers was considered inferior to the “old centers” of Christianity. Each encounter was, rather, a manifestation of how the evangelizing church was fulfilling its mission in the world.” Indeed each encounter was a demonstration of Christianity’s universal appeal. Moreover, none of the centers, “old” or “new”, considers itself the sole bearers of the Christian mission. Each center sees itself as a full participant in the evangelizing mission of the church. (cf. Lamin Sanneh’s “Whose Religion Is Christianity”, 36ff.).

Seen from this perspective, the new southward shift in Christianity is not a matter of worries but the triumph of its universal expansion and adaptability to all peoples of the world. Sanneh adds that the history of Christian expansion and adaptability enabled Christianity itself to break the cultural barriers of its former domestication in the Northern hemisphere to create missionary resurgence and renewal that transformed the religion into a world faith. He opines that there is much to be gained by respecting this historical missionary paradigm. Modern African Christianity provides us with an indispensable example of what is at stake.

In this context, Sanneh presents an argument about the limitations of the concept of mission as one-way traffic, from the West to the rest of the world. In fact, his critique of the idea of Christendom advanced at the Edinburgh 1910 Missionary Conference. He makes the case most forcefully in connection to African experience:

“African Christianity has not been a bitterly fought religion: there have been no ecclesiastical courts condemning unbelievers, heretics, and witches to death, no bloody battles of doctrine and polity, no territorial aggrandizement by churches; no jihads against infidels, no fatwas against women, no amputations, lynchings, ostracism, penalties, or public condemnation of doctrinal differences or dissent. The lines of Christian profession have not been etched in the blood of enemies. To that extent, at least African Christianity has diverged strikingly from sixteenth and seventeenth-century Christendom.” (Lamin Sanneh, “Whose Religion Is Christianity” (39).

This is the perspective from which Sanneh advances his basic argument on intercultural process in the history of Christian mission. In the first place, he acknowledges that statistical weight has moved Africa firmly into the Christian orbit, and that happened only a few years ago, which is why the notion “Africa is a Christian continent” is so novel and dramatic. But we should bear in mind that Christianity from its origins was marked by serial retreat and advance as an intercultural process. Bethlehem and Jerusalem were superseded by Antioch and Athens, while Egypt and Carthage soon gave place to Rome. Rival centers multiplied the chances of further contraction and expansion. Then it was the turn of the North Atlantic world to inherit the mantle before the next momentous phase brought the religion to the southern hemisphere, with Africa representing the most recent continental shift. Sanneh writes:

“These developments went beyond merely adding more names to the book; they had to do with cultural shifts, with changing the books themselves. This serial feature of the history of Christianity is largely hidden from people in the West now living in a post-Christian culture. Even in Africa itself the churches were caught unprepared, and are scarcely able to cope with the elementary issue of absorbing new members, let alone with deeper issues of formation and training” (“Whose Religion Is Christianity” (36-37).

The point here is that the concept of Christendom (“mission as one way-traffic”) imprisons the study of non-Western Christianity within a Western theological framework and thus impoverishes understanding of its nature and significance. It entrenches the notion of Christian missionary movement as “one-way traffic”, as a movement from the “old Christendom” (the West) to the so-called “non-Christian land” (or “mission land”).

The missionary significance as well as the real Christian identity of Christians from the former “non-Christian land” or (“mission land” – southern continents), is thus suppressed by the concept of “Christendom” – mission as one-way-traffic. Moreover, the experience of Christendom perhaps predisposes Westerners to think of religious phenomena in terms of permanent centers and structures of unilateral control.

These were some of the strands in contemporary missiological thinking, Lamin Sanneh, masterly discussed in his writings from an African perspective. They all constitute the strength of his scholarship and contribution to mission studies, World Christianity and Islam.

Conclusion

In Professor Lamin Sanneh’s religious itinerary, life experience and scholarship, whether as a Muslim or Christian, we meet an example, a model of what a typical African scholar is likely to undergo. That is, whenever he comes to grips with the religious and cultural layers that underpin our African cosmology and religious worldview amidst other world religions and cultures in our increasingly pluralistic and globalizing world.

His, was the effort of an African scholar, struggling to reclaim his colonial dispossessed cultural and religious identity, and contribute to African renaissance in theological and missiological scholarship. It was an effort aimed at overcoming the crisis of cultural and religious identity of African people, and rediscovering the riches of African religious and cultural traditions after over five-hundred years of colonialism, the Western and Arab conquest of the Black continent.

Professor Lamin Sanneh had been on international scene for most part of his adult life and scholarship itinerary. It is not surprising therefore, that most of the colleagues evaluated his scholarly contribution to World Christianity, Islam and Missions, sometimes with the lens of Western scholarship other than African that it truly was.

However, as we have tried to demonstrate in this tribute in his honor, the fact remains that, beneath Professor Sanneh’s writings, is the effort of an African scholar. His was an effort of a former African Muslim, now converted to Christianity, doing a dialogue with his African reality and background. From that baggage of his religious experience and itinerary, he grappled with the question of the place of his people in the increasingly globalizing pluralistic world of different religions, cultures and philosophy of life. In his scholarship of dialogue with religions and cultures, World Christianity and Islam, his African experience, always loomed large.

Over his 30-year at Yale Divinity School as well as stints at the University of London and two Pontifical Commissions, Sanneh brought World Christianity and African presence to the forefront, drawing a global network of scholars and friends around his scholarship in the fields of study and research.

My condolences to his widow, Sandra Sanneh, their son Kelefa, and daughter Sia, as well as to his numerous friends and students in the world of academia and sciences. With the demise of Lamin Sanneh, Africa has lost one of his greatest scholars and theologians of our time. May God receive his good soul and strengthen the family he left behind. Adieu Professor Lamin Sanneh!

Francis Anekwe Oborji

(Professor Ordinarius of contextual theology and inculturation at the Pontifical Urbaniana University, Rome).

END

Be the first to comment