The kind of influence that the likes of Lamidi Adedibu wielded is a metaphor for the character and level of Nigerian politics. Godfathers still exist in today’s politics and the new godfathers are just as messianic and as arrogant as their predecessors were. Violence also remains an instrument of persuasion and enforcement…

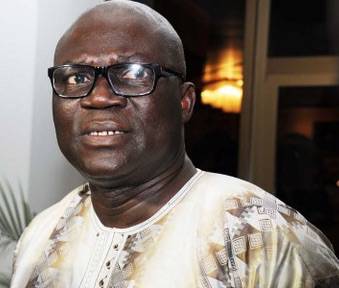

It has been ten years since the self-styled “strong man of Ibadan politics”, Chief Lamidi Ariyibi Akanji Adedibu, died. He died on June 11, 2008. I do not recall seeing many tributes or advertisements in the newspapers or other media commemorating his life and legacy. There was no public lecture or any important statement from those who were his protégés. That this is so is a useful lesson to today’s political Godfathers and henchmen in Nigerian politics who behave as if history has already assigned to them an immortal space on its pages.

Lamidi Adedibu was a colossal presence in the politics of Ibadan, and Oyo State for more than 50 years. Ibadan has a tradition of colourful politicians who wielded enormous influence: Adegoke Adelabu, the brilliant orator and intellectually gifted personality who authored Africa in Ebullition, and whose use of the phrase “peculiar mess” got transliterated by his illiterate audience as “penkelemesi”; Chief Mojeed Mobolanle Agbaje, the first Ibadan man to become a lawyer, and son of Alhaji Salami Agbaje of Ayeye, Ibadan who was the richest man in Ibadan in his time and the first to ride a car (1915) and build a house with cement. Also, Chief Meredith Adisa Akinloye, an alumnus of the London School of Economics (LSE), founder of the Ibadan People’s Party (IPP), chairman of Ibadan City Council and in the Second Republic, chairman of the National Party of Nigeria (NPN); and Alhaji Busari Adelakun, the “Eruobodo” (“the river fears no one”) of Ibadan politics. There is hardly any other Ibadan indigene, apart from these gentlemen, who has been more influential in shaping the tone and shape of Ibadan politics and by extension, the politics of Oyo State. Local Ibadan politics is a combination of thuggery, populism, inconsistency, clientelism and intellectual opportunism, with service to the people thrown in as a lower measure.

Lamidi Adedibu lacked the intellectual gifts of Adelabu, Agbaje, and Akinloye, or the oratory of Adelabu – he was much closer to Busari Adelakun, who was his mentor. In an instructive book titled What I saw in the Politics of Ibadanland, Adedibu has already given his own eye-witness account from his beginning days with the Ibadan People’s Party and the Action Group, and later the National Party of Nigeria during the Second Republic, but he truly came into his own as the main godfather of Ibadan politics with the ascendancy of the Peoples Democratic Party in 1999 and especially in 2003 when he was recruited by President Olusegun Obasanjo for his second term bid. He filled the vacuum created by the exit of Alhaji Busari Adelakun, and in that aspect, he established himself as a master of the game, using violence, mass appeal, and philanthropy to determine political outcomes. During the Second Republic, Alhaji Busari Adelakun was credited with having helped Chief Bola Ige of the Unity Party of Nigeria (UPN) to become governor.

The main task of that branch of Ibadan politics represented by Adelakun and his followers, was to help deliver the votes, by any means possible. Adelakun would go from one polling booth to the other, and ensure that his clients won the vote. He was later rewarded with the position of a commissioner (first, Local Government and Chieftaincy Affairs and later, Health) in the Bola Ige government. Both men would soon fall out, and Busari Adelakun resigned in anger. He famously swore that nobody could ever occupy a position that he, Adelakun, left in anger. It then happened that his immediate successor in the Ministry of Local Government and Chieftaincy died in the hands of his own sibling. He was beheaded. Adelakun’s successor in the Ministry of Health also suffered stroke. He, on account of this, became a mythical figure. He would later defect to the National Party of Nigeria (NPN) with the threat that he would get Bola Ige removed as governor. He supported Chief Victor Omololu Olunloyo, who eventually became governor. His word came to pass. But the Olunloyo government was short-lived. General Buhari struck in December 1983 and Adelakun and other NPN chieftains were herded into detention. He took ill in jail and died subsequently.

He held court and juggled the balls from his extensive home in Molete, Ibadan. That was where he held court. He was Ashipa Olubadan but he had his own palace – where he decided the political fortunes of politicians who came to him for help, or persons seeking political appointments. It was not for nothing that he was known as “Alaafin of Molete”.

It was Lamidi Adedibu who sustained this tradition of prominent Ibadan politicians playing the role of the godfather, and masters of the politics of clientelism. Unlike Adelakun, he didn’t have to follow the able-bodied boys, masquerading as members of the National Union of Road Transport Workers (NURTW), who snatched ballot boxes in those days and stuffed them. He had the entire city under his control in a manner nobody else before him did. Every major thug in the town reported to him, and he used them against the opponents, but he also, at the same time, took very good care of the ordinary people who delivered the votes to ensure victory for his clients and friends. Lamidi Adedibu, with the failure of the Alliance for Democracy in the 2003 election in Oyo State, became effectively the most influential politician in Ibadan politics, Oyo State politics, and one of the leading lights of the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). He held court and juggled the balls from his extensive home in Molete, Ibadan. That was where he held court. He was Ashipa Olubadan but he had his own palace – where he decided the political fortunes of politicians who came to him for help, or persons seeking political appointments. It was not for nothing that he was known as “Alaafin of Molete”.

His home was a palace unto itself. He was also the exponent of “Amala politics” – what is now known as the politics of stomach infrastructure. Every day, Adedibu kept his home open for the ordinary people of Ibadan. Whoever was hungry knew that if they went to Adedibu’s home, they would get a good plate of piping hot amala and a drink to wash it down. Ordinary people who could not pay school fees or hospital bills or rent went to him in his palace to ask for help. He supported them willingly. He was not a herdsman but he had a mini-ranch in his home, at any time, there were more than a dozen cows waiting to be slaughtered to feed the people, goats also, and rams and pigeons. Everyday in the Adedibu home was like a festival. He reportedly kept more than 100 vehicles, to be mobilised at short notice to pursue any political cause. The whole of Ibadan city came to regard Adedibu as the real government: He ran a government of his own. It wasn’t long before he became a national figure of real importance.

Prominent politicians visited him at home, and as they did, they brought bags of money, which in any case, Adedibu shared to the electorate. The politicians who took him as their godfather expected him to help them deliver the votes on election day and the people who went to his house to eat and collect money waited on him to tell them how they should vote in every election. He would soon become so influential that the then chairman of the PDP, Dr. Ahmadu Ali described him, at a point, as the “garrison commander of Ibadan politics.” President Olusegun Obasanjo also visited him at home once, welcomed by a cavalcade of drums and pageantry, and he ended up describing him as the “father of the PDP”. Even politicians from other parts of the country, who may not have needed him in their own constituencies, patronised him all the same. In his own immediate political constituency, his boys did as they wished. They unleashed violence on political opponents, while the state authorities looked the other way. Adedibu was above the law. He was the ultimate godfather. He once quipped: “…Let me tell you, constitution or law, that is for you men. God has his own law.” There was no one like that before him, and there has been no other like that after him. He projected himself as a Robin Hood, but he didn’t really like the poor, he used them for his own relevance.

In 2003, he had reportedly helped to install Senator Rasheed Adewolu Ladoja as governor of Oyo State. He himself said so. That is what people like him do – they would help to install a client in a position of political authority. They would then afterwards collect rent in the form of cash and appointive positions and exercise influence over public policy. Adedibu and Ladoja soon fell out. Adedibu told the public that he had a prior agreement with Ladoja that he must pay to him, every month, 50 per cent of the state’s security vote, which was at the time about N30 million. Ladoja reneged, insisting that the security vote was meant for security. The godfather became angry – he retorted that he was the main security of the state and did Ladoja realise that money was spent to get him into office? He swore to get Ladoja removed. And indeed he did. Eighteen out of the 32 members of the state House of Assembly, acting on Adedibu’s instructions, met and impeached Ladoja. His deputy, who was also an Adedibu protégé, was immediately installed as governor. After taking the oath of office, one of Christopher Adebayo Alao-Akala’s first assignments was to go straight to Adedibu’s home to pay homage. He went down on all fours to say, “thank you.” Ladoja would later be reinstated by court order 11 months later, but the godfather had made his point.

Our politicians have learnt to exploit the people’s poverty. Political godfathers capitalise on this and turn it into a strategy. When the people are rescued from the poverty trap, they would be less susceptible to the greed and exploitation of politicians. Institutions also have to be built and strengthened to check the menace of godfathers…

The kind of influence that the likes of Lamidi Adedibu wielded is a metaphor for the character and level of Nigerian politics. Godfathers still exist in today’s politics and the new godfathers are just as messianic and as arrogant as their predecessors were. Violence also remains an instrument of persuasion and enforcement, even if since Adedibu’s exit, the level of violence in Ibadan politics has progressively reduced, across the country, many politicians routinely patronise thugs and enforcers. “Amala politics” still exists in the form of “stomach infrastructure” – even when some politicians do not turn their homes into a public kitchen and abattoir, they patronise the people by bribing them with motorcycles or boreholes. In Benue State, Governor Samuel Ortom distributed wheel barrows with the inscription: “Gov. Ortom for you”. In another state, a serving APC senator donated an electric pole to a community as constituency project and took photographs; in Kano state, Gov. Abdullahi Ganduje bought noodles, eggs, and beverages to empower tea hawkers. Now that we are in an election season, some other politicians will distribute cooked food, bags of rice or photograph themselves eating at amala joints or buying roasted corn by the roadside.

Our politicians have learnt to exploit the people’s poverty. Political godfathers capitalise on this and turn it into a strategy. When the people are rescued from the poverty trap, they would be less susceptible to the greed and exploitation of politicians. Institutions also have to be built and strengthened to check the menace of godfathers and their boys who decide electoral choices on the people’s behalf and by so doing, frustrate democratic expression.

As a human being, Adedibu was obviously a strong grassroots mobiliser. He was also a strong religious and community leader – he built 18 mosques – but his legacy of stomach infrastructure and political manipulation could not endure in the long run. One week after his burial, his political acolytes returned hoping that his family would sustain the feast. They were turned back. The pots and pans used for cooking had been packed aside. Over 90 mattresses used by the army of boys that thronged the “palace” had been packed together in a heap to be disposed off. The amala-seeking crowd went over to the home of Alhaji Azeez Arisekola-Alao, an Ibadan politician and entrepreneur, hoping he would provide “amala”. Arisekola was a prominent philanthropist but he wasn’t running a public kitchen in his home. One of Adedibu’s sons, ended up in politics and became a senator, but he did not follow in his father’s footsteps. Another son reportedly described the late politician as a “dishonest politician.”

Today, the Molete palace is desolate. The in-house ranch has disappeared. The Nigerian electorate, should be reminded that when a politician offers them food in exchange for their votes, that food will soon digest and end up in the toilet, and you’d need to eat again. When the politician dies, or leaves politics or no longer needs you, you’d still have to eat. It is always better to vote wisely and focus on the need to build and strengthen public institutions for the people’s benefit.

Reuben Abati, a former presidential spokesperson, writes from Lagos.

END

Be the first to comment