It is with more than a little shame and discomfiture that the state of Lagos, and indeed the country at large, should receive the latest Global Livability Index, which rated Nigeria’s commercial nerve centre as the third worst city in the world for humans to live in. In the 2018 edition of an annual report released by the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), Lagos was ranked 138 out of 140 nations, being only ahead of Dhaka (Bangladesh) and Syria’s war-torn Damascus.

People in certain quarters, taken by a bizarre idea of patriotism that shuns introspection, have attempted to discountenance this report, saying that a group of foreigners should not be telling Nigerians about Nigeria, or Lagosians about Lagos. Although there have always been allegations that western-originated economic and social reports often tend towards the disparagement of the so-called ‘Third World,’ this latest report of the EIU should be taken as a pointer to the myriad of problems that Lagos has been facing. It should also better serve as a nudge to the relevant authorities to recognize the need for the amelioration of the plight of the city’s inhabitants.

For no one can deny that there is a problem. And for the many restless souls who trudge daily through conditions that are indeed unlivable, it matters less who points out the challenges than whether something is done to make life more bearable and truly excellent in that designated ‘Centre of Excellence’.

The parametres used for evaluation are unquestionably critical to true development, ranging from stability and healthcare to education, environment and infrastructure. Despite the activity of the state government towards a general improvement, Lagos, it must be said, still falls terribly short in the delivery of these key services.

This suggests that a new approach is altogether necessary, one of which reexamines notions of development and redefines its standards. Infrastructure, for example, is more than the mere construction of highways through slums, or the erection of mega buildings on sand-filled land for the exclusive consumption of the rich and powerful; it also has to do with the systems and amenities (such as electricity, security, pipe-borne water, effective waste disposal, and smart transportation) that keep a city running from day to day.

These, indeed, are the things that operate beneath the physical structures to which the very term “infra-structure” should properly apply. And it is instructive that the high-flying cities in the earlier and latest reports of the EIC are places where these things are not in deficit.

Japan’s Osaka, for example, moved up six places to third position and only a fraction of a percentage point away from Melbourne, which has just ceded the prime position to Vienna, and this impressive leap is credited to the city’s “improvement in scores for quality and availability of public transportation, as well as a consistent decline in crime rates.”

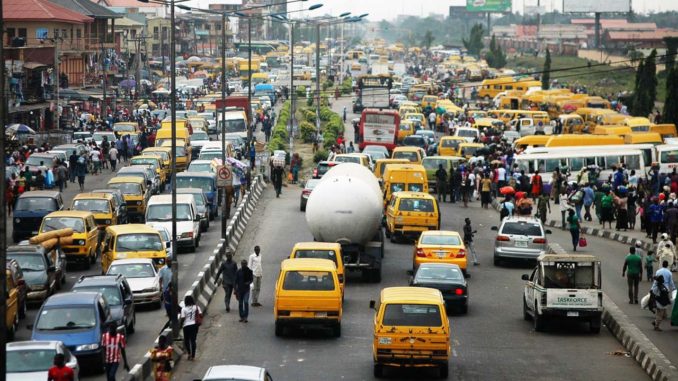

Lagos, by contrast, sports everywhere the objectionable scene of commuters stranded at bus stops or walking en masse along highway curbstones, disappointed time and again by the non-flow of the metropolis. Even the home, for many, is no haven. Housing is one of the great quandaries that the Lagos section of humanity continues to grapple with, and the grappling continues precisely because government is not handling it well. How landlords are allowed, for example, to keep building substandard facilities and renting them out at exorbitant rates is still a source of great wonder to many of the city’s residents and regular visitors. But perhaps it should not be such an enigma, since even the government’s own projects do not appear to give much more hope, and many “low-cost housing estates” have turned out only to be lowly and costly.

The most fundamental thing that needs to be done is for leadership to redefine itself, and rather than playing politics with governance or playing to the gallery, government should be with vision and purpose. Rather than building an urban, concrete and asphalt jungle where although opportunities abound the cost of harnessing them is high and often cavalier, leadership should take responsibility for the processes (mentioned earlier) that are essential to keeping a city alive.

While the state government does have an obvious responsibility towards the development and organization of Lagos, the Federal Government also owes the commercial capital of the nation, which houses among many other things its income-raking ports, a degree of conscionable debt. It should therefore honour its obligation to the state. After all, on 3rd February 1976, the then Head of State, General Murtala Mohammed while proclaiming Abuja as the nation’s new capital, specifically pledged federal government’s continued commitment to Lagos he designated as a ‘Special Area’. Besides, military leader then promised to work Lagos into the 1979 constitution then in the works. This covenant on Lagos has never been fulfilled.

Perhaps a good place to start is to treat the state with a legally binding acknowledgement of its special status. The shame of Lagos is the shame of Nigeria, after all.

END

Be the first to comment