The significance of KSA’s work as a musician lies in his ability to weave such a diverse array of elements into a distinct form that is immediately recognisable. It unfolds as sequences of improvised vocal and instrumental narratives carefully put together, exploring diverse and free-flowing themes, gracefully embodied, and rendered conversationally with the audience in ways that break social and cultural boundaries.

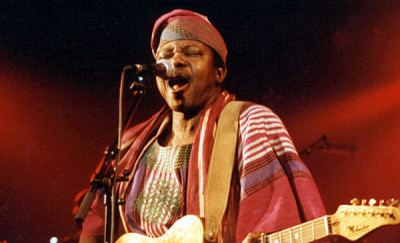

Celebrating King Sunny Ade

King Sunny Ade’s transformation from his Oshogbo/Ondo humble beginnings into global stardom is marked by two recurring attributes: single-mindedness and perseverance. It is a story about a person who knew he had a calling to become a professional musician, and worked resolutely towards achieving his goal. Drawing on the values of self-dignity that his mother had taught him, and relying on his knowledge of indigenous performance, King Sunny Ade (KSA) proceeded to Lagos and began a new phase of his life as a young man. In Lagos, he identified those who would help him achieve his desire. One of them was Moses Olaiya, who offered him an opportunity to apprentice as a musician. The other was Chief Tunde Amuwo, who provided him with a set of musical instruments, as well as a space to perform. KSA, building on the support of these two men and many others, has formed one of Africa’s most successful bands, released over one hundred albums, helped to create PMAN (Performing Musicians Association of Nigeria), resisted the urge by global musical networks to change his style of music, and created a musical genre that, although eclectically sourced, is unique in its projection of African-grounded performance aesthetics.

KSA’s story also reveals an ability to effectively navigate complex contours of human relationships. He encountered problematic recording companies, dealt with protesting band members who decided to walk out on him just when a studio recording was about to begin, and struggled against record pirates bent on undermining his right of financial benefits. Most remarkable however is his ability to create a distinctive juju style that has become a pan-Yoruba musical language and a model for upcoming musicians within and outside Nigeria. KSA’s unique juju style, his àríyá socio-aesthetics, as I want to characterise it, exemplifies a multidimensional performance spectacle in which topical social issues are conveyed through a performance mode that is marked with brilliant musicianship and engaging in its thematic fluidity.

KSA’s recent tour of the United States, forming part of his 70th birthday anniversary, provides an opportunity to reflect on, and celebrate, his career as an outstanding figure in global popular music. As I pondered how to frame my essay, it became clear that making a case for a full integration of popular music studies into the Nigerian music curriculum, especially in the universities, should form an important element of my homage to KSA. My plan in this essay is therefore to celebrate KSA by discussing his music, highlighting the significance of his work as a musician and drawing attention to the pedagogical value of popular music. My methods here are simple: provide a brief ethnographic account of one of his US tour concerts to reveal salient features of his music, review some arguments about the significance of popular music, and make a strong case for the teaching of popular music in African universities. All these are framed within the context of a celebrative essay targeting one of Africa’s greatest musicians.

KSA’s 2016 Performance in Lowell, USA

The notice was quite short. Although I had informed my contact of my intention to conduct an interview with KSA during his US tour, and although I did get an initial nod, the final confirmation did not come until just a few hours before his concert in Lowell on July 30th, 2016. I packed my ethnographic tech equipment, and started the journey to Lowell, just about 80 miles away from my home. Located in Middlesex County, Lowell is the fourth largest city in the state of Massachusetts.

KSA’s concert was part of the annual Lowell Folk Festival, an event that attracts many other musicians, and features culinary and craft displays. Lowell city was, as expected, in a festive mood. Traffic was diverted away from the city centre because many of its open spaces had been converted into demarcated concert arenas. Ethnic foods from various parts of the world were served for a fee in many different kiosks. A country music band was performing at one of the main arenas. But I was more interested in locating the specific venue of KSA’s show, which, as I later found out, was a short distance away from the country music stand. Local residents that I interviewed then informed me that KSA’s show was a special headline performance and therefore reserved for much later in the evening. I seized the opportunity to sample a Vietnamese dish, after which my wife and I made our way to the venue of his concert. It was inside a covered arena with a modest stage, and an audience of about 300 people, mostly white fans, but with a significant number of blacks dominated, as expected, by Nigerians. The age profile of the audience was between the bracket of 30 and 50 years. The audience included new initiates, as well as diehard fans that had followed KSA for years and were always on the lookout for him.

The size of KSA’s band that evening corresponded with the modest size of the stage and audience. Just about 10 performers, made up of four gángan hourglass drummers, a bembe drummer, a bass guitarist, a keyboardist, another guitarist who complemented KSA’s guitar lead, a conga drummer, and another member playing the Western drum set. As usual with KSA’s band, instrumentalists doubled as singers and dancers, with the exception of two members who only sang and danced, forming a close trio with KSA. A loud ovation erupted as KSA came on stage to join the rest of his band. After a short exchange of greetings with the audience, KSA wasted no time in starting the concert, rending many favourite oldies, including “Ori Mi Yeo Ja Fun Mi,” “Ma Lanu Ma Korin Mafi Gbe Oluwa Ga,” and “Kiti kiti Kira Kita,” all treated to skillful dance movements, the types of which have endeared KSA’s juju music to local and global audiences for over fifty years. He paced around the stage, moved his body up and down to his own music, shaking his legs, waist, and shoulders in ways that astonished and captivated the audience.

At one point, a bemused lady standing next to me asked whether this was indeed Sunny Ade. She found it hard to believe that a 70-year old man could dance with such flair and energy. The graceful physicality of KSA’s dance movements simultaneously enchanted and surprised her. The performance arena became increasingly energised as the band continued to generate dense webs of vocal and instrumental phrases intricately woven together. KSA conversed with the audience, made different sections of the audience sing–and then humorously awarded grades based on how each section performed. He indicated clearly that a major objective of his music was to build bridges among peoples, and promote social harmony.

KSA’s Àríyá Socio-aesthetics

The multicultural sources of KSA’ music demonstrate how his music connects peoples and cultures. Yoruba hourglass drums, Afro-Cuban conga drums, European guitars, keyboard and drums all represent vital elements of his soundscape. The varied instrumental, vocal and movement resources of his music resonate with manifold stylistic qualities too: European tonality, Nigerian pentatonic singing, Yoruba dance-drumming language (especially the alujo mode), and Afro-Cuban rumba. Western guitars are organised to simulate the layering technique of Yoruba drum language, while the keyboard generates occasional punctuations and folksy interludes, rather than merely providing harmonic direction.

KSA’s use of Yoruba gángan drums often precludes the distinctive role of the master drummer as obtained with the hierarchic structure of Yoruba drumming. In KSA’s music, gángan drums, save for their occasional improvised melo-rhythmic punctuations, are used mainly to sustain and reinforce the electrifying groove of the music. The vocal component of the performance, led by KSA, is outlined in a series of story-telling, praise-singing phrases, and packaged within a call-responsorial format typical of African performance style.

The significance of KSA’s work as a musician lies in his ability to weave such a diverse array of elements into a distinct form that is immediately recognisable. It unfolds as sequences of improvised vocal and instrumental narratives carefully put together, exploring diverse and free-flowing themes, gracefully embodied, and rendered conversationally with the audience in ways that break social and cultural boundaries.

Popular Music and Music Education

Articulating the significance of KSA’s àríyá style, in terms of both its social topicality and captivating performance, provides the context for reflecting on Nigeria’s system of music education, which presently tends to favour Western classical music and, to a lesser extent, “traditional” African music with precolonial roots. The marginalisation of popular music (the category to which belong the works of musicians like Sunny Ade, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, Osita Osadebey, and P-Square, to mention just a few examples) is a reminder of how educational policies of the British colonial era and the aesthetic preferences of the West have continued to influence what is taught in many African institutions. Eminent Africanist musicologist, Kofi Agawu, emphasises this point in his book, Representing African Music: Postcolonial Notes, Queries, Positions (Routledge 2003) by reflecting on the situation in Ghana, and observing that “while popular music such as highlife served an important social function as dance music, its incorporation into the curriculum was slow to emerge” (p. 120).

As Peter Manuel has observed in his book, Popular Musics of the Non-Western World: An Introductory Survey (Oxford University Press, 1988), the initial denigration of popular music in Europe rested on two main ideological planks. Conservative elitism saw in popular music a cultural expression that threatened the canonical status of Western classical music, as well as the social values that the music designates. In addition, neo-Marxist scholars, like Theodore Adorno of the Frankfurt School, tended to characterise popular music as banal, standardised, and a cultural opium imposed by the elite on the masses as a ploy to divert their (the masses’) attention away from social inequalities and economic exploitations of which they are victims. I must note that these two broad views do not account for the various nuanced ways in which popular music has been discussed by scholars. It is also important to state that these negative stereotypes about popular music have now faded significantly. Popular music studies have become a more visible academic subject in European and American universities over the past thirty years or so. But this is yet to be the case in Nigeria, in spite of the efforts by some music departments in the country’s universities to promote the teaching of popular music.

It is essential to draw attention to the many positive qualities of popular music, notably, its capability to facilitate interaction amongst a socially and culturally broad group of people as demonstrated in my discussion of KSA’s Lowell concert earlier. The democratic qualities of popular music are highlighted in its proclivity toward social topicality and the cultivation of musical styles that are accessible, yet profound. It is furthermore noteworthy that, KSA, like many Nigerian and African musicians, has effectively configured a platform for showcasing African musical heritage across the globe and sustaining important African social values and cultural practices. This is remarkable, given the competitive global world in which we live and where Africans have to struggle to maintain their identities. It is because of these qualities that African popular music represents an important socio-musical context for imparting crucial musical and extra-musical knowledge. In addition, musical genres like highlife, afro-beat, juju, afro-rap, and afro-beats all provide an invaluable frame for students and scholars seeking to understand African principles of musical form and composition, instrumentation, improvisation, and stage presentation, to mention but a few.

I should clarify that I am not in any way discouraging the teaching of Western classical music in African universities. Not at all. It is a great tradition that has a lot to offer to students. My argument is that we should complement our emphasis on classical music and traditional music with an organic approach to the teaching of popular music. Reflecting on my own undergraduate studies in the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, I recall how we focused mainly on European classical music, along with a tokenistic attention given to indigenous African music. Popular music was completely absent in the curriculum. That experience would later condition my research to focus on the works of African composers of art music and, later, indigenous music traditions. I have however recently realised the need for an academic shift that accords recognition to the works of musicians like KSA, a decision that has resulted in a modest list of publications, including my Popular Music In Western Nigeria (IFRA 2014), which explores the relationship between social themes, musical style and social patronage in western Nigeria. Many other scholars, including Christopher Waterman, Michael Veal, Tejumola Olaniyan, Olusoji Stephens, Ijeoma Forchu, Albert Oikelome, to mention just a few, also have been active in the study of Nigerian popular music. Waterman’s groundbreaking book (Juju: a Social History and Ethnography of an African Popular Music, University of Chicago Press, 1990) is particularly significant in pioneering a serious study of Nigerian popular music. Also commendable is Professor Onye Nwankpa’s current effort at promoting and studying the music of Rex Lawson at the University of Port Harcourt.

Appreciating KSA’s Àríyá Socio-Aesthetics

Sunny Ade’s music provides the context for understanding the social, aesthetic and pedagogical value of popular music. It draws attention to how popular music provides a space for social participation and reflection, promotes cultural identity, and connects communities. Like those of his colleagues in the popular music profession, KSA’s skills in music composition and performance, his management skills as a bandleader, his marketing strategies in the music business, should all form an invaluable part of the music curriculum.

Finally, it is significant to note that the success of KSA as a musician of global status emanates from certain core elements of his personality: being amiable, and strong-willed; hardworking, yet playful; successful, yet humble. He is a no-nonsense executive with a strong passion for excellence.

As we celebrate KSA’s seventieth birthday, I pray for God to grant him many more years of active and productive musicianship and service to humanity, great health, and abundant blessings. AMEN!

Bode Omojola, a Five College Professor of Music, teaching at Mount Holyoke College, was the founding secretary of the Musicological Society of Nigeria, now Association of Nigerian Musicologists (ANIM).

END

Be the first to comment