To truly do justice to Abiola’s memory and Nigerians, the federal government should release the results of the June 12, 1993 election, acknowledge his victory at the polls and recognise him as president-elect. This is the only way to truly bring closure to what remains a traumatic period of our history.

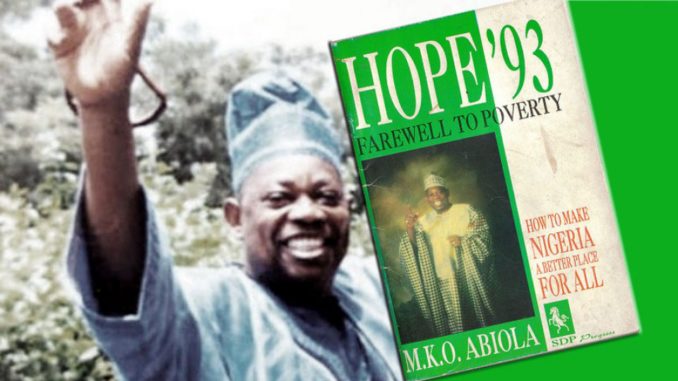

President Muhammadu Buhari’s declaration of June 12 as Democracy Day and his posthumous conferment of the nation’s highest award, the Grand Commander of the Order of the Federal Republic (GCFR) on Moshood Abiola, the winner of the June 12, 1993 election has elicited both applause and controversy. With an election year looming, it is no surprise that every act of the government is interpreted as “politically motivated.” Quite why the phrase “politically motivated” should be used as an epithet in the context of politics is a mystery. Politicians being politically motivated is the natural order of things, especially on the eve of an election. Altruism in politics is the rarest of unicorns.

To place Buhari’s act in perspective, some historical analogies are necessary. In late 1982, President Shehu Shagari granted an unconditional pardon to the former Biafran leader, Emeka Odumegwu Ojukwu to return to Nigeria 12 years after he had fled into exile following the collapse of the Biafran secession in January 1970. Both the presidential pardon and Ojukwu’s return were greeted by jubilation in the South-East. Naturally not everyone was happy. Post-civil war regimes had long cast Ojukwu as the arch villain of that conflict and a former attorney general of Nigeria, Dr. Graham Douglas argued that Ojukwu’s reception gave the impression that rebellion pays. For the Shagari administration, there were political calculations at work beyond the humanitarian value of letting a defeated warlord return home. The ruling National Party of Nigeria was trying to break the stranglehold of the opposition the Nigeria People’s Party led by Nnamdi Azikiwe in the South-East.

In a similar vein, on October 1, 1982, Shagari conferred the nation’s highest honour, the GCFR, on his main opponent, Chief Obafemi Awolowo, not only for services previously rendered as a federal commissioner but undoubtedly with the aim of softening one of his severest critics and defusing partisan animus ahead of the 1983 election. It is the nature of politicians to seek to kill more than one bird with one stone. Their craft, after all, is politics not philanthropy. That a politician’s act is politically motivated does not mean that it cannot be appropriated by the forces of good. Thus, however cynically self-serving its motives are, the Buhari administration’s announcement offers an opportunity for such positive appropriation.

June 12 has always made more sense than May 29 as Democracy Day. If we are going to set aside a day to reflect on our nation’s long march to democratic governance, which is better than June 12, the anniversary of a watershed event in our history? May 29 has always seemed forced and inauthentic, reeling from a poverty of mythological depth and lacking the historical heft of June 12. President Buhari’s consecration of June 12 has righted a symbolic error.

A Reluctant Rebel

On June 12, 1993, the heady sense of hope and exhilaration as Nigerians voted to end eleven straight years of military dictatorship was palpable. In the process, they also dismantled formidable myths and orthodoxies about electoral maps and identity politics by choosing two Muslims – Moshood Abiola and Babagana Kingibe – as their leaders. It was a decision that defied conventional wisdom about what sort of political pairings are electable. It has been argued that rather than representing a post-sectarian leap by the electorate, the election of two Muslims simply represented the wild card move of a people that had grown tired of military rule. This argument is untenable as Nigerians could have simply voted for the opposing ticket – the safer and more straightforward partnership of Bashir Tofa and Sylvester Ugoh. The fact that they opted for the unconventional pairing had as much to do with the people’s readiness to venture into uncharted territory, as it did with the ticket’s popularity. Abiola secured 58 per cent of the votes cast (a higher percentage than what Buhari won in 2015).

In this moment of what may seem like supreme honour for Abiola, there is a risk that by appropriating June 12, the establishment will also seek to water down its significance and obscure its true meaning. On this point, vigilance is necessary. June 12 is about the unsung legions that risked life, limb and livelihood and challenged a despotic regime.

One is keenly aware that Abiola’s pedigree as a crony of military regimes and sponsor of coups made him the unlikeliest standard bearer of democratic values and not a few people felt that the nullification of his victory was his karmic comeuppance. Abiola was, in many respects, part of Nigeria’s problematic elite. He was, in the words of Adebayo Williams, “the reluctant and ill-qualified champion of popular grievances.” It is a measure of how comfortable he was with the military elites that Abiola was more amenable to relying on Abacha and a clique within the military to dislodge the interim government headed by Ernest Shonekan rather than on a mass protest by the activists of the Campaign for Democracy. By the time he and others realised Abacha’s capacity for Machiavellian mendacity, it was too late.

History has come full circle. Abiola sponsored the coup that overthrew Buhari when he was Head of State in 1985 and ushered in Ibrahim Babangida. Buhari would later become a member of the Abacha regime which incarcerated Abiola and now two decades after as president, is seeking to rehabilitate him.

Beyond Abiola

But June 12 is about more than just Abiola. As Arthur Nwankwo once observed, “History, in a deeper sense, is the unfolding of trends, and not just the eccentricities of individual players.” Consequently, June 12 is also about the events that followed that historic election. Its annulment by the Babangida regime marked the demystification of the armed forces as messianic interventionists and the exposure of the venality of the military ruling caste. June 12 exposed the complicity of civil society in the ascendancy of military dictators, a complicity rooted in a longstanding misbegotten belief in the redemptive potential of benevolent tyrants. It was this belief that led figures in the pro-democracy movement, ranging from Gani Fawehinmi and Beko Ransome-Kuti to Bolaji Akinyemi and even the iconic anti-establishment troubadour, Fela Anikulapo-Kuti, to back Abacha’s coup on the implausible premise that he was going to restore Abiola’s mandate.

This dalliance with Abacha eventually created a schism within the Campaign for Democracy between Beko’s faction, which sought a pragmatic alliance with the military and Chima Ubani’s faction which argued that no good, let alone democracy, could possibly emerge from such an alliance. Their differences proved irreconcilable and terminally splintered the CD. June 12 also revealed the grand perfidies of the political class which, possessed by individual, partisan, sectional and egotistical lusts, betrayed its calling to lead the Third Republic and aborted what ought to have been a critical juncture in Nigerian history. June 12 is also about the bitter lessons learnt during the dark age of dictatorship at the colossal expense of much innocent blood, the devaluation of human life and the casual liquidation of real and imagined adversaries by regime death squads. Until Abacha, Nigerians had always reveled in the illusion that the Kafkaesque monstrousities of Idi Amin and Mobutu could never manifest on their shores. The events that followed the annulment of June 12 stripped us of such self-deceiving notions.

In this moment of what may seem like supreme honour for Abiola, there is a risk that by appropriating June 12, the establishment will also seek to water down its significance and obscure its true meaning. On this point, vigilance is necessary. June 12 is about the unsung legions that risked life, limb and livelihood and challenged a despotic regime. It calls for a rededication to democratic values, the rule of law and human rights, which under the current administration have all too often been in abeyance. It carries a reminder that the struggle for democracy is far from over.

June 12 can be claimed by sectional irredentists and counter-claimed by democrats. What a date means in the national consciousness is determined by the conviction and clarity of those who appropriate it. There is no peace with justice and no justice with memory. Nigeria is a nation at loggerheads with its past.

One of the sadder consequences of the annulment was the tragic collapse of the national electoral consensus that produced the June 12 victory and the deepening of tribal trenches around the struggle to reclaim that mandate. The belief runs deep that Abiola was denied the presidency by northern martial elites because of his ethnicity. The reality was more nuanced. The Babangida era had promoted the delusion that army officers were uniquely endowed with the aptitude for statecraft and it is likely that even if Tofa had won the election, rival cliques in the army, having acquired such an uncontrollable taste for Aso Rock, would still have annulled the polls and seized power. In the end, even Babangida became hostage to the overambitious soldiers that had been the spear and shield of his regime and opted to leave office as a survivor rather than a dead hero.

The singular act of the annulment and how it was interpreted in the years that followed has sown a profound mistrust in our politics that makes it nearly impossible to imagine a pairing of candidates that is as defiant of identity politics as that which won the 1993 election. It is this mistrust that has led some to erroneously see the recognition of June 12 as a Yoruba sentimentality, rather than a national milestone and has engendered ill-feeling instead of empathy.

Memory, Symbols and Justice

The politics of symbolic days is not unique to Nigeria. When President Ronald Reagan created a national holiday in memory of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1983, it ended the campaign for such an honour for the civil rights advocate that began immediately after his assassination in 1968. Not all Americans were enthused and there were those who saw King as a communist sympathiser and anti-American subversive. And like any good politician, Reagan, who was initially not supportive of the idea of a national holiday for King, was not oblivious to the impact his decision might have among African-Americans and moderate white voters. His decision, in a sense, was politically motivated.

Part of a nation’s ongoing conversation with itself is a contestation of memory and meaning. Symbolic dates and days can be claimed and counter-claimed by disparate interests. Thus, the declaration of May 29 as Democracy Day irked some who remembered it as the anniversary of the declaration of the Republic of Biafra in 1967 – a sacred day for Biafran separatists. January 15 is Remembrance Day, a day on which we commemorate the sacrifices of the armed forces and those that have fallen in the line of duty. But to some, it is the anniversary of Nigeria’s first coup d’etat or the “revolution” which ended the First Republic in 1966. That event itself is defined either as a murderous mutiny or an idealistic revolution by different constituencies. January 15 is also the anniversary of the surrender of Biafra to federal forces in 1970.

The posthumous conferment of Nigeria’s highest honour on Abiola deserves interrogation. While it is understandable that many would rather express gratitude for the belated recognition of a figure that has been officially marginalised in the two decades since his death, we must look this gift horse in the mouth.

To some polemicists, these disparate and contradictory interpretations of dates and events indicate Nigeria’s profound internal incoherence. But such contestation is necessary before consensus can emerge. June 12 can be claimed by sectional irredentists and counter-claimed by democrats. What a date means in the national consciousness is determined by the conviction and clarity of those who appropriate it. There is no peace with justice and no justice with memory. Nigeria is a nation at loggerheads with its past. The reclamation of history and the construction of national memory which are necessary for healing are tasks for progressives. A shared recollection of events is also useful for national mobilisation.

One of the great debilities of civil society is the inability of Nigerians to find solidarity in their suffering, despite the amply democratised woes inflicted upon them by rogue elites. This deficiency subsists because each constituency believes that its claim to victimhood is superior to the claims of others. Armed with such arrogance and insensitivity, various groups simply suffer in their ethnic and sectarian silos rather than make common cause. The inability to articulate the various instances of victimhood as one broad tapestry of tribulation, despite the universality of marginalisation, is arguably the greatest failure of contemporary Nigerian politicians and civil society in general. June 12 is a reminder of a historic injustice, so universal in its affliction, that all progressive Nigerians can rally round it.

As Arthur Nwankwo once wrote, while Yakubu Gowon’s prompt general amnesty to Biafrans after the war “prevented a social wound from becoming cancerous,” Shagari’s pardon of Ojukwu was “a balm that will dry up that social wound.” He also described Ojukwu’s return as an event that was “to individual Igbos, the symbolic release of their chained half, the concluding paragraph in the general amnesty essay.” The Buhari administration’s efforts to rehabilitate Abiola can be as socio-politically cathartic as these other measures. But it must go further.

The posthumous conferment of Nigeria’s highest honour on Abiola deserves interrogation. While it is understandable that many would rather express gratitude for the belated recognition of a figure that has been officially marginalised in the two decades since his death, we must look this gift horse in the mouth. Symbolism matters a great deal in statecraft and the administration is clearly betting heavily on the symbolic weight of June 12 and the GCFR award. However, what is worth doing is worth doing well and there is a thin line between symbolism and cosmetic superficiality. These measures still fall short righting a historic wrong. To truly do justice to Abiola’s memory and Nigerians, the federal government should release the results of the June 12, 1993 election, acknowledge his victory at the polls and recognise him as president-elect. This is the only way to truly bring closure to what remains a traumatic period of our history.

Chris Ngwodo is a writer, analyst and consultant.

END

Be the first to comment