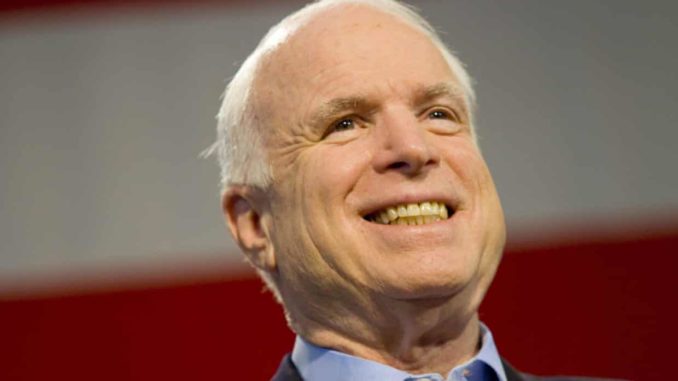

Senator John McCain of Arizona, who has died aged 81 after suffering from brain cancer, was for many Americans an authentic national hero. The son and grandson of admirals, he was a pilot who, shot down over North Vietnam, inspired his fellow prisoners by his courage under savage beatings and torture so severe that to the end of his life he could not lift his arms above his shoulders. He refused offers to be sent home, to deny his captors a propaganda victory, and inspired older and higher-ranking prisoners with his exceptional bravery and leadership in jail.

As a Republican senator and as a candidate for the presidency he combined fierce traditional patriotism with an unpredictable independence of mind. The conservative journalist William Buckley said McCain was “conservative but not a conservative” – conservative, that is, in his instincts and beliefs, but not a member of the conservative movement. Barack Obama, McCain’s victorious rival for the presidency, when he learned that McCain had been diagnosed with cancer, commented: “Cancer doesn’t know what it’s up against.”

Only President Donald Trump, who avoided the draft for Vietnam, refused to acknowledge McCain’s heroic status. “He’s not a war hero,” Trump said. “He’s [called] a war hero because he was captured. I like people that weren’t captured.”

In the Senate, to which he had been elected in 1986, McCain acquired such a reputation as an independent-minded Republican that in 2004, John Kerry, the Democrats’ presidential candidate, asked him to be his vice-presidential running mate. McCain refused, saying he was “a pro-life, deficit hawk, free trade Republican”.

In 2000 he looked for several months the likely winner of the Republican candidacy before he was beaten by George W Bush in one of the dirtiest political campaigns in living memory. In 2008 he came even closer. The previous year he had again been the frontrunner for the Republican nomination, but lost ground because of his support for the war in Iraq. By March 2008 he had won the Republican nomination easily and in August selected the Alaska governor, Sarah Palin, as his running mate. He hung on within a handful of percentage points of Obama until the November election.

He was a stubborn maverick. He backed gun control and voted for liberal positions on immigration, even though they were unpopular in Arizona. Understandably, he was critical of the Bush administration’s torture of “enemy combatants” in the Guantánamo Bay detention camp and elsewhere. But although he insisted that he did not want American troops to remain in Iraq any longer than needed (one of his sons served there as an officer in the Marines), he also said he would support staying there for 100 years if that were necessary to do the job.

In domestic politics, too, once he had emerged as the presidential candidate, he came closer to the Republican mainstream. He came out for tax cuts, which his opponents said favoured the wealthy even more than those advocated by Bush. He proposed policies to reduce drastically the US’s dependence on imported energy. Yet in 2001 he teamed up with the liberal Democratic senator Russ Feingold to push through a major reform of election campaign finances.

McCain was an exceptionally complex man, with a political career that often took him in contradictory directions. He consistently opposed the excessive influence of money and lobbyists in Washington, though Democrats pointed out that many of his advisers were lobbyists.

Despite his courage, both physical and moral, he was far from a saint. Capable of great personal charm, he had a volcanic temper and could be enormously rude, even on occasion to his wife in public. This may have been exacerbated by his sufferings in Hanoi, but he was never a model of conventional virtue. As a young man he was a hard-drinking, hard-partying tearaway who excelled at wrestling and boxing.

McCain told off-colour stories and memorably once said “Fuck you!” to a fellow senator on the floor of the Senate chamber. The thread that connected all his political instincts was a strong, old-fashioned patriotism. That explained his initially unpopular stance on Iraq. It also explained why he continued to be more sympathetic to immigrants than many Republicans, given that the US was a nation founded on immigration. He was deeply proud of his country but nonetheless felt strongly that much in American public life should be reformed.

McCain’s patriotism was inherited from an originally Confederate family who once owned a 2,000-acre plantation with slaves in Mississippi. His grandfather was an admiral in the US navy during the second world war and was in command at the naval battles of Leyte Gulf and Okinawa. John McCain III was born to John Jr and his wife Roberta (nee Wright) in the Panama canal zone, where the family was stationed at the time. As a child he attended more than 20 schools as his father moved from base to base. When a political opponent once called him a carpetbagger, meaning that he wasn’t a genuine resident of Arizona, he was able to retort that the place he had lived longest was Hanoi.

After attending the Episcopal high school in Alexandria, Virginia, he followed his father and grandfather into the naval academy at Annapolis, Maryland, where he raised a good deal of hell and graduated in 1958 near the bottom of his class. He was sent for flight training, first to Florida, then to Texas, where he was almost killed in an accident.

In July 1967, shortly after arriving in Vietnam, he was at the centre of an even more spectacular incident. His A-4 Skyhawk fighter was preparing for launch when a rocket from an F-4 Phantom was accidentally fired across the deck of his carrier USS Forrestal. It hit the full fuel tank of McCain’s plane and knocked two bombs loose. Before one of the bombs exploded, McCain climbed out of the cockpit, then dropped onto the burning deck, where he tried to free another pilot. The fire caused by the explosion killed 134 sailors, destroyed at least 20 aircraft, and threatened to sink the carrier.

McCain struck up a lifelong friendship with the New York Times reporter RW “Johnny” Apple, who was sent to cover the accident. It was not long before the two of them were carousing together in Saigon. In October 1967 McCain was shot down by a ground-to-air missile and landed in a lake near Hanoi. As he ejected from the plane, he broke both arms and a leg. A mob gathered, stripped him and started kicking him. Then he was taken to the notorious prison known as the “Hanoi Hilton” and tortured almost daily.

When the North Vietnamese found out that his father was commander in chief of the US Pacific command, McCain was offered the chance to go home early. He refused unless his fellow PoWs were freed too. In a nightmare world of smuggled notes, terror and carefully calibrated defiance, he earned the unstinting admiration of his fellow prisoners. He was, they agreed, the bravest of the brave.

After he was finally released in 1973, he returned to naval service. He first commanded a flight training unit called, appropriately, the Hellrazors. Then in 1976 he became the navy’s chief lobbyist with the Senate in Washington, and succeeded in persuading Congress to appropriate funding for a new super-carrier – against the wishes of President Jimmy Carter’s administration. The experience opened his eyes to another field for service.

In 1965 McCain had married Carol Shepp, a model from Philadelphia. He adopted her two sons, Douglas and Andrew, and together they had a daughter, Sidney. While McCain was a prisoner in Vietnam, his wife was badly injured in a car accident.

In 1979 he met Cindy Hensley, the daughter of the wealthy owner of the Anheuser-Busch beer franchise for the rapidly growing city of Phoenix, Arizona, whom he married in 1980, following his divorce from Carol. He went to work for his wife’s father, building a political power base among the influential contacts he made in that state, and decided to run for Congress.

He was first elected to the House of Representatives in 1982, then, in 1986, to the Senate. He replaced Barry Goldwater, the outspoken conservative who was heavily defeated as the Republican candidate in the 1964 presidential election, but who in the process helped to revive conservative politics in the US.

In the Senate his mentor was John Tower, the hawkish Republican from Texas. But he also worked closely with the liberal Democrat John Kerry, trying to find out whether Americans were still being held prisoner in Vietnam. He got into trouble in 1989 as one of five legislators who appeared to be protecting a corrupt savings and loan company promoter. He annoyed many of his colleagues by his rejection of what is known as pork barrel politics, especially the habit of allowing senators and congressmen to “earmark” large sums for pet projects in their states or districts.

McCain was exonerated by the Senate ethics committee, but the episode left him with a distaste for the influence of money in politics, and no doubt also with a desire to demonstrate his own honesty. What annoyed them more was that McCain and his wife were now rich even by the standards of Capitol Hill. She was worth more than $100m, and he once forgot how many houses he owned.

In 1999, he announced himself as a candidate for the 2000 presidential election. He defeated Bush in the New Hampshire primary, and seemed to be the favourite going into the South Carolina primary. He was beaten there by a particularly nasty dirty trick. Voters were asked what they would feel if they learned that McCain had a daughter by a black mistress. The McCains had in fact adopted Bridget, a Bangladeshi girl, from one of Mother Teresa’s hostels. “I believe that there is a special place in hell,” said McCain, for the Republicans who had concocted this smear.

With the 9/11 attacks, McCain’s old-fashioned patriotism kicked in. He became one of the strongest supporters both of Bush’s homeland security legislation and in due course, of the invasion of Afghanistan and the second Iraq war. “It’s a fight,” he said of the war at the 2004 Republican convention, “between right and wrong, good and evil.”

His continued support for the war ordered by a president he neither liked nor trusted was the background to the collapse of his bid for the presidency in 2007. But by the end of that year he was back in the race and challenging for the lead.

Throughout 2008 he displayed his usual tenacity and more than usual self-control. He continued to attack Obama as a celebrity candidate with too little experience, especially in national security matters.

There was a double irony about McCain’s political fortunes. A man whose career was founded on military virtues and old-fashioned patriotism was trapped by his loyalty to an unpopular war. A politician whose appeal derived from his spontaneous human responses was brought down when he tried to behave like any other professional politician. After Trump was elected president, McCain was one of the few Republicans to challenge the new president openly at a time when only his party could restrain Trump’s irrational policies.

As the new chair of the powerful Senate armed services committee he became one of the most important men in Congress. He had already let it be known that what he wanted on his gravestone was, “He served his country.”

At the end of July 2017 he returned to the Senate after an operation to remove a cancerous tumour from his brain, above his left eye, and made his frustrations clear by calling for co-operation and compromise: “Our deliberations can still be important and useful, but I think we’d all agree they haven’t been overburdened by greatness lately … We’re getting nothing done.”

He made his own push for a bipartisan approach to healthcare reform as one of three Republican senators to vote against the repeal of Obama’s Affordable Care Act. The Senate Democratic leader, Chuck Schumer, observed, “I have not seen a senator who speaks truth to power as strongly, as well and as frequently as John McCain.” In September McCain maintained his position, rejecting a Republican-only solution and calling on both parties “to arrive at a compromise solution that is acceptable to most of us, and serves the interests of Americans as best we can”.

Illness then kept him away from Washington, but in his memoir The Restless Wave, published last May, he called for a return to old-fashioned Republican values, pointed to the danger of the information onslaught being waged by Russia, and described how in December 2016 he had passed on the dossier compiled by Christopher Steele alleging that Moscow held compromising material on Trump to the FBI. Both in the book and in an HBO documentary, John McCain: For Whom the Bell Tolls, he expressed regret that he had not chosen his friend and former Democrat senator Joe Lieberman as his 2008 running partner rather than Palin.

This month Trump failed to mention the senator when signing the defence spending bill named after him. McCain’s death came the day after his family announced that he had decided to to discontinue further medical treatment.

He is survived by Cindy, their children, Meghan, John, James and Bridget, and the three children of his first marriage.

• John Sidney McCain III, politician, born 29 August 1936; died 25 August 2018

• This article was amended on 26 August 2018. The Steele dossier was passed on to the FBI in December 2016 rather than December 2017.

END

Be the first to comment