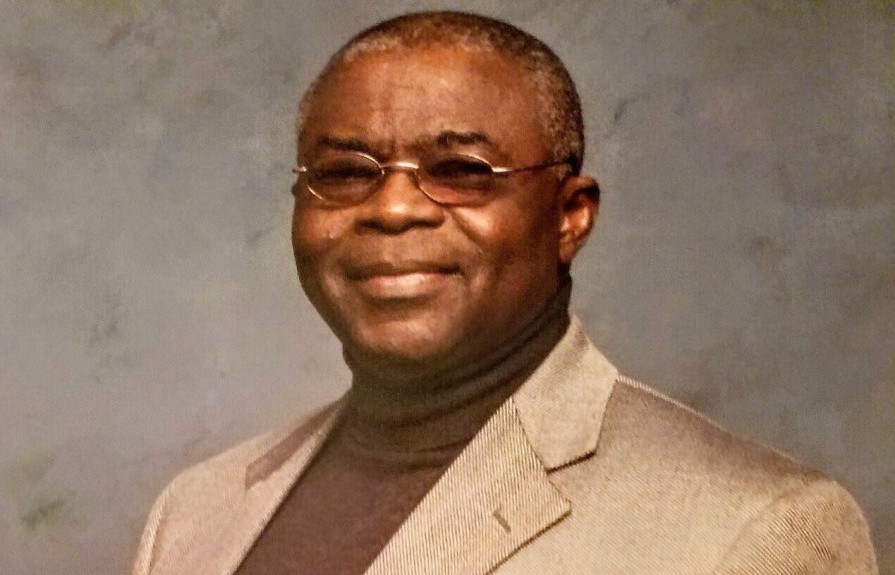

…until his illness in 2011, Professor Okpewho was one of the few senior scholars of African humanities with whom I had very close intellectual dealings.

“Using language with style,” the teacher mutters, looking away, “the Bible would say ‘Adam knew Eve.’” Wait! Does the fleeting demurral come out of a sense of rectitude, of decorum to match the nuance appropriate to the topic at hand? Does the professor imagine that his students have no notion of the original sin as a bodily act? But, then, this is a class on the use of language, “ENG 206: Language and Style.” No prior familiarity with the Bible is assumed, although declaration of knowledge of figures of speech ought to come with the registration.

This lecturer has no affectations. No histrionics. No distractions. No false affability, calculated to court undergraduate following. Just competent, deeply informative, punctual attitude to the material at hand. Undergrads love that. No unexcused absence at weekly tutorials, and no late submission of assignments, most definitely.

At the University of Ibadan in the 1980s, Professor Isidore Okpewho’s ENG 206 was one of those “Dugbe” courses (so-called after the largest market in Ibadan, because of the size of the enrollment) in which it was hardly possible for professors to know students by name. Chances were that you would make an impression if you spoke up during tutorials, usually with fewer than twenty participants. I took this course, attended tutorials when my involvements in the theatre allowed it, and said what I thought, but escaped his attention largely because I was not an English major. Outside of classroom, my most memorable encounters with him were seeing him play tennis at the Staff Club (sporting his Mike Tyson hairstyle), and seeing him at the Arts Theatre in October 1988 to observe rehearsals for Wole Soyinka’s Opera Wonyosi, in his capacity as the chairman of the Organising Committee for the UI@40 celebrations, for which a production of the play, directed by the late Dapo Adelugba, was commissioned.

All of that changed after I enrolled in the doctoral program at Cornell University. Somehow, Professor Okpewho found out that I had a major interest in cinema, an area with which he was hoping to become familiar. When he and art historian Nkiru Nzegwu planned for another volume in the African diaspora series (following the groundbreaking one he co-edited with Ali Mazrui and Carole Boyce Davies in 1999), he invited my participation in the symposium held at the SUNY Binghamton in April 2006. The volume that came out of that symposium was titled The New African Diaspora, published by Indiana University Press in 2009.

Before the symposium, I had occasion to meet him at another conference. He was no longer the formal, aloof professor using stylised language in a high-seriousness tone, but a lively, somewhat avuncular senior colleague, tickled by a former student’s recollection of his demeanour in the lecture room. In early summer of 2005, he received a fellowship to spend a semester at the Smithsonian Institution, and he needed someone to teach his courses for the fall. He reached out to me, proposing some enticing offers that I considered flattering; I had however accepted a tenure-track position at Indiana University, and regretfully declined.

Over the next half decade, until his illness in 2011, Professor Okpewho was one of the few senior scholars of African humanities with whom I had very close intellectual dealings. While the New African Diaspora volume was still in press, I guest-edited a special issue of Farafina, the new literary journal published in Lagos by Muhtar Bakare. Looking for writings suitable for the theme “Home and Exile,” I came across Okpewho’s presidential address at an annual conference of the International Society for Oral Literature in Africa, and decided to include an excerpt of it in the issue. It was his turn to be flattered: as someone who began his career in publishing, Okpewho was keenly interested in the promotion of creative writing. (Classics of Nigerian literature like Sonala Olumhense’s No Second Chance and Lekan Oyegoke’s Cowrie Tears were written for his Creative Writing class at Ibadan in the late 1970s.) With his current status as a foremost, much-prized scholar of oral literature, he could not really keep abreast of trends in publishing initiatives. He hadn’t known of Farafina, and in this new initiative he saw an opportunity for a Nigerian edition of his latest novel, Call Me By My Rightful Name. I played a mediator in this process also, although the publication did not materialise for reasons I can now no longer recall.

In those days, when he reflected on the fact of being edited and published by a former student, a student who learnt the use of figurative language under his tutelage, he would laughingly cite the African proverb that says “When a rodent attains old age, she is suckled by her offspring.” His humility in this respect was far-and-away outstanding. Wanting to initiate a new course on African cinema, he sought my advice, and I enthusiastically prepared a synoptic idea of the thematics in the field, sending this alongside a list of titles that I thought would make a good introductory course. We jointly reviewed his proposed syllabus and discussed mechanisms for teaching films with running time longer than the duration of a class session. Video-streaming was still a new phenomenon for teaching purposes, and to add this to upper-level undergraduate instruction in a vibrant area of screen media would be ordinarily daunting.

Professor Okpewho more than rose to the occasion, and his email at the end of the semester was sufficient testimony: “My class on African cinema went VERY well this semester, and I definitely intend to make it a yearly offering. Even our Cinema department has crosslisted it. I just returned the portfolio of reviews put together by each of the 43 students.”

Politically, he did not evince the fiery advocacy of a Biodun Jeyifo or the earnest passion of a Niyi Osundare. Call him a liberal, but I was startled and embarrassed by a statement in the speech he gave during dinner at the Binghamton symposium, which suggested that new African immigrants in the US might just want to concern themselves more with self-improvement and less with political activism. Late in his career, however, and especially in writings modulated in a rather public voice, he appeared as becoming more mindful of global black creativity as operating in irreducible adversarial contexts, to use Guyanese writer Wilson Harris’ timeless phrase.

We will miss you, Prof.

Akin Adesokan teaches in the Department of Comparative Literature, Indiana University, Bloomington, USA.

END

Be the first to comment