As a creative writer, novelist, poet and literary critic, Isidore Okpewho made reaching for perfection a great reason for being around in any genre or discipline. Always with an inter-disciplinary focus, he refused to follow the herd. Once he made a commitment, he ploughed his own furrow and refused to be distracted by praise or rebuke.

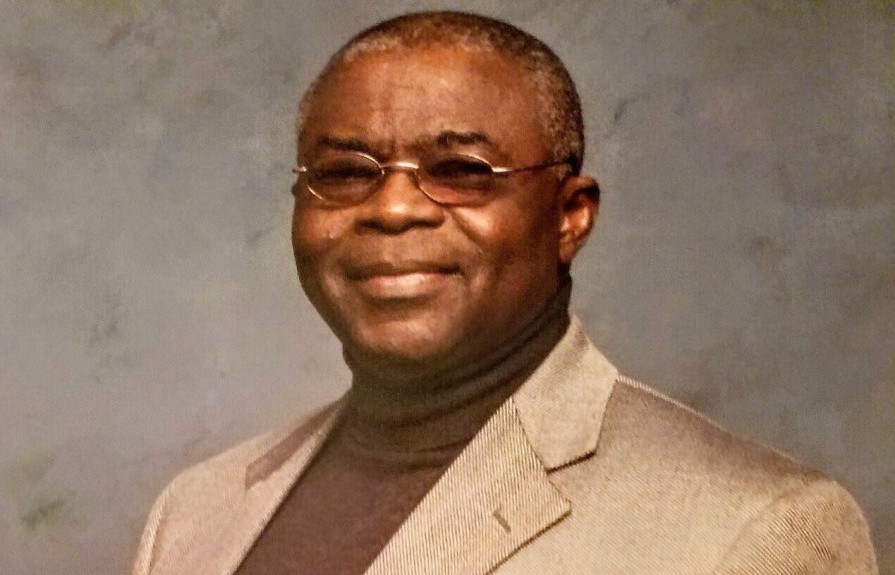

It is truly sad news that Isidore Okpewho, unforgettably warm-hearted, civilised, accommodating and a gentleman without humbug, has passed on at the age of 74. A professor at the State University of New York at Binghamton since 1991, and a President of the International Society for the Oral Literatures of Africa (ISOLA), he is acclaimed, across the world, as a virtuoso performer among authoritative figures in the research, practice and teaching of oral literature. After a First Class Honours degree in Classics from the University of Ibadan, he began his career in publishing at Longmans Nigeria where, as an unpublished poet seeking outlet, I first met him.

Affable, and genuinely serious-minded, Isidore left publishing for the University of Denvers, USA, to get his PhD which he capped with a D.Litt at the University of London. He returned to publishing at Longman publishers but pulled back to academia, teaching for fourteen years at the University of Ibadan, his alma mater, before returning to the United States, where his academic career had started sixteen years earlier at the University of New York at Buffalo (1974-76). A year at Harvard University between 1990 and 91 convinced him to remain in the United States at a time when Nigerian academics under military dictatorship were being sacked for teaching what they were not paid to teach, and were being paid pittance for a take-home that could not take them home.

As a creative writer, novelist, poet and literary critic, Isidore Okpewho made reaching for perfection a great reason for being around in any genre or discipline. Always with an inter-disciplinary focus, he refused to follow the herd. Once he made a commitment, he ploughed his own furrow and refused to be distracted by praise or rebuke. Formidable in every sense, his intellectual prowess always had an intimidating edge that he never flaunted even when lesser mortals over-rated themselves. His output as a writer, a veritable master of cultural literacy, has had few parallels. He was the kind of scholar that other long-standing professors would say: when I grow up, I want to be like him. This was the result of his outstanding performance in two seminal, paradigm-changing works of scholarship The Epic in Africa: Toward a Poetics of the Oral Performance (1979) and Myth in Africa: A Study of Its Aesthetic and Cultural Relevance (1983) which gave him not just a head start as a master in the study of oral literature but a special vantage as an interrogator and formulator of theories of knowledge and humanistic studies that primed Africa as a centre of civilisation in her own right. The works dredged the commonality of human reflexes at the base of aesthetic production between different races and nationalities. Given his knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman Culture, there was a solid substructure upon which he built a highly universalist temper. In a lot of ways, it explains his grasp and forthright engagement of the grand theories of modernist and post-modernist scholarship and consequently, his concern with the interconnectivity of narratives of knowledge systems which proves his quintessential mark as a scholar.

Generally, not being a nativist, Isidore Okpewho stood with African civilisation without allowing multiple, incongruous, moralities to influence his reception and judgement of other climes. As a classicist, with deep immersion in ancient civilisations, he knew how not to let the bragging propensities that go with all cultural geographies, especially imperial ones, to lay exclusive claims to human values that cut across cultural boundaries. Particularly, in The Epic in Africa, he uncovered for serious engagement the reality that the oral and scribal cultures of the world share common principles of poetic composition in too many respects to warrant the parochial necessity to privilege one civilisation above the other. His Myth in Africa re-drew the map of scholarship in relation to received Western notions that distanced Africa from other cultures on the question of mythologies and mythmaking in general. Based on fieldwork in various parts of Nigeria, especially in the Igbo and Ijaw parts of the Benin Delta, and drawing on researches in other parts of Africa, he formulated an aestheticist theory which invoked performance in the arts as plausible transformers of the way societies behave or change modalities of action.

For an Urhobo whose mother was Asaba, it may well be said that he had to have a keen appreciation of cultural diversities and their interactions as the grit of his vocation. I recall interviewing him about this in Morocco, during an African Literature Association (ALA) conference on his book, Once Upon A Kingdom, which deals with the relationship between the Benin Kingdom and their cultural siblings on the West of the Niger. Even where we differed, I thoroughly enjoyed the ease with which he could immerse himself in local cultures and then link them to universal themes such as the incipient rise and rise of ethnic nationalism. It was after Once Upon a Kingdom that he began to dredge the racial memory of African Americans, addressing and seeking redress for collective psychologies of grandchildren who, in their sub-conscious, were living through ferments in ancestral Africa that even their fathers could not intuit, but they had to resolve before they could tackle the civil rights issues of their day.

Racial memory, as he has threshed it, is not just about what happened to the enslaved through the Middle Passage, the gore after the landing, and the blithe summer of the freeborn without a memory of slavery. This came out quite well in his novel, Call Me By My Rightful Name in which he literally romped through the ancient Ekiti dialect of the Yoruba language and Culture with an effortless pitch that told of the harrowing dislocation which slavery wreaked on both sides of the Atlantic; right into the civil rights movements of O we shall overcome. On this score, it is quite a treat to follow his deep historical and anthropological insights, in full fictional flight, as depicted in this novel. The point, so creatively and poignantly woven into Call Me By My Rightful Name, is that even those in the new world whose parents had no physical contact with Africa could be so implicated in what happened in Africa before Trans-Atlantic enslavement. It simply calls for the tie between homeland and Diaspora to be studiously kept alive in order to have clear perspectives on how to go in a divided world.

…the great pull of Isidore Okpewho’s scholarship into the 21st Century was building up and assessing the dimensions and directions of linkages between Africa and the African Diaspora. It added a twist to his academic interests and a broadening of those interests to accommodate Africans outside Africa in terms of their interaction with the continent.

The beauty of it is that Okpewho’s novels and general literary creativity, while benefitting from so many diverse associations, maintain simple, absorbing touches of empathy. This is even-handedly displayed in the Victims, dealing with the question of polygamy, The Last Duty, on the travails of the civil war outside Biafra, and his penultimate, Tides, which deploys a superb epistolary form to unearth threats of environmental biocide and political insipidity in the face of sheer homicide in Nigeria’s Niger Delta. The novels, with truly folkloric zeal, read like conversations between friends celebrating the resilience of the individual spirit in times of collective disorientation. We meet an author who is at home with the innocence of childhood and the rueful world of the grown up in equally hapless situations.

Never to be down-graded is that Isidore Okpewho was, first and foremost, a teacher. On this counterpane, his ground setter for the study of Oral literature was his 1992 book, African Oral Literature: Background, Character, and Continuity (Indiana University Presss). Quite an ambitious take, after it, was the elevating concern that yielded the grand collaboration with Ali Mazrui and Carol Boyce Davies in editing the path-breaking and incomparable book The African Diaspora: African Origins and New World Identities (Indiana University Press, (1999). Consequently, the great pull of Isidore Okpewho’s scholarship into the 21st Century was building up and assessing the dimensions and directions of linkages between Africa and the African Diaspora. It added a twist to his academic interests and a broadening of those interests to accommodate Africans outside Africa in terms of their interaction with the continent.

May I note that, sad as it is to miss him, I am more like wanting to raise a shout for a man who was dogged in always doing things so right that whatever one remembers of him brings out vintage heartiness. He was a classicist and anthropologist, always able to put his knowledge of ancient and modern times to good account without being fazed by the new fangled theories of modernism and post-modernism. Forever on top of aesthetic seepages and values that help in configuring national and cross-national identities, he gave the arts their due not as passive but active elements in how people perceive social and cultural spaces. For him, it was ever about knowledge and its shared valuation. As G.G. Darah reminded us in his tribute, Isidore Okpewho’s passing away hits home with Hampate Ba’s appreciation of how it is like a whole library burnt down when an old man dies. It is a tragedy spelt at the level of the knowledge industry. This is especially the case when one considers that the critical mass of intellect that was driven out of the country in the eighties into the nineties, is thinning out, and continues to haunt us with sheer opportunity costs and, worst of all, terminal cases of loss.

Irony of ironies, it makes it imperative to celebrate the fact that, but for his relocation to the United States, his chance of surviving up to the age of 74 and with the high level of intellectual production that has accompanied his artistic and academic odyssey, would have been so much less prodigious. This touches the issue of how much greater Nigeria would have been in the comity of knowledge-driven nations if all those Nigerian masters of the Word in the United states were all at home and producing. To think of it! One realises how our society never creates good opportunities to celebrate the real avatars in our midst until too late. It rankles because, in a country without regular literary journals and the necessary soirees that give contemporary arts their great moments, yes, in a society in which those who ruined the economy and the university system are still having a great showing in the public space as if waiting to be given laurels for their destructive engagements, whole armies of our best minds are still being driven off-shore. It makes past encounters that were of little moment, when they first occurred, to begin to spring wider associations.

Surely, one such moment I cant forget was during the burial of Isidore Okpewho’s mother at Asaba. It was like a convergence of the Nigerian literati in solidarity with him. Dancing through the streets with the ritual carriage on his head, he was acknowledging our toasting of his scion-ship in ceremonial fashion. Suddenly, he veered off and brought the funeral throng in a virtual stampede to where I stood on the other side of the road. Stomping around me, he lunged, without preambles, into an argument, about an opinion I had just expressed, that weekend, in my The Guardian review of his book, Myth in Africa. It was a review, now part of my book, A House of Many Mansions, which Stanley Macebuh and Yemi Ogunbiyi had thrust upon me as a test of intellectual nerve. Coming face to face with the author on the streets of Asaba, I found I had to step obligingly to the beat of the ceremonial drums, while we entered this intense argument about his aestheticist theory of myth.

The great part is that, as a creative writer and scholar, Isidore Okpewho, wrote his hands black and left so much that can save many lifetimes, many generations to come, from the wastage that would have hounded their endeavours but for the humungous scholarship that he has left as guard and guide. He was always the great mind, who moved from oceanic dimensions to brooks without losing his swimmingly authoritative stride and stature.

The drums and gongs were pounding away. Around us, the women sang and danced and stomped along with us, as we punched the air from one leg of the argument to the other. But the man of ideas was intent on slugging it out over my insistence that a myth without ritual becomes mere metaphor. As ever, full of erudition, he conceded the point but refused to accept the implication I drew from it. Using one example after another, he kept reiterating the view that I missed the point he was making in his book.

I still can’t stop laughing each time I recall that some people thought our argument, which the drums were contesting, and his dancing around me, were part of the funeral ritual. He made it look that way to justify his moving the funeral throng off its course. With some embarrassment, I kept nudging him about my not wanting to disrupt the ceremony. He shrugged it off. It was his ken to lead the funeral throng to where it had to go. So we argued some more before I literally had to run from the scene because I was beginning to enjoy the arguments. Surely, it was an incident that we were not going to run away from or let become a mere metaphor. We had to re-enact it again, and gave it ritual content when, some years later, once upon a visit to the United states, I grey-hounded a night bus journey from New York to Cornel and then to Binghamton, to see him.

We, sure, had another, but more conversational jig, after attending a lecture by Amiri Baraka, who was the visiting lecturer at a University event on that day. We talked about projects and tasks confronting African writers and scholars, a subject on which he never stopped reminding me of Professor Abiola Irele one of the few great legends of his standing, whose passion on the subject of pooling knowledge for Africa, rises from romance to sheer myth in the face of a society at home that seems too far gone. Assuredly, in fine intellectual fettle, still talking like a Senior Boy from St. Patricks Asaba, where he had his secondary school education, Isidore had the assurance of someone with so much work still to be done. Although he was recuperating from an illness, also because his wife, Obiageli, was away to see one or other of their four children Ediru, Ugo, Afigo, and Onome, we could talk a little far into the night. It was our last meeting.

I had promised to return to Binghamton again when I would be able to meet the whole family and if need be re-enact the jig. But as such promises go, time disposed otherwise. Here we are. On September 4, 2016, he was gone.

The great part is that, as a creative writer and scholar, Isidore Okpewho, wrote his hands black and left so much that can save many lifetimes, many generations to come, from the wastage that would have hounded their endeavours but for the humungous scholarship that he has left as guard and guide. He was always the great mind, who moved from oceanic dimensions to brooks without losing his swimmingly authoritative stride and stature. He won the 1976 African Arts Prize for Literature and, in 1993, the Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for Best Book Africa. His prestigious fellowships in the humanities included “the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (1982), Alexander von Humboldt Foundation (1982), Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford (1988), the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute at Harvard (1990), National Humanities Center in North Carolina (1997), and the Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation (2003). He was also elected Folklore Fellow International by the Finnish Academy of the Sciences in Helsinki (1993).” Not forgetting that he was a Fellow of the Nigerian Academy of Letters and a recipient of the Nigerian National Merit Award, it is such a good feeling to know that he was honoured while he was at it; and especially, that hereafter, his life’s work remains secured. His essays, a gargantuan production, will not just remain scattered in journals across the world. They have entered the stream of production by Professor Toyin Falola, assessor per excellence, one of the greatest minds that Nigeria has ever produced, who has promised to take the job in hand. Blood on the Tides: The Ozidi Saga and Oral Epic Narratology has just been published through his auspices by the University of Rochester Press to be followed by his collected essays. Although the marvellous literary and academic productions by Nigerians abroad hardly manage to enter this country that lacks a respectable bookshop and library culture, it is good to know that when, someday, we catch up with the rest of the world, the work done by Isidore Okpewho and others forced into expatriation in the years of the locust, still in place, will be there as quite a harvest awaiting all of us. Incidentally, how we could catch up was always part of Professor Isidore Okpewho’s unending concern. For his immeasurable contributions to that quest, certainly, he has earned his rest. May his soul rest in perfect peace.

Odia Ofeimun, a poet, essayist, political and cultural historian, writes from Lagos. He is author of the acclaimed The Poet Lied, several other collections of poetry, dance dramas, and the book of essays Taking Nigeria Seriously, among others.

PemiumTimes

END

Be the first to comment