There is no evidence that President Buhari’s antipathy towards the free market and multilateral development institutions has changed. There is also no evidence that Professor Ibrahim Gambari, unlike the late Mr. Abba Kyari, shares these views. Will the new chief of staff therefore seek to lessen the influence of his principal’s worldview, which has had ghastly consequences, on economic policy?

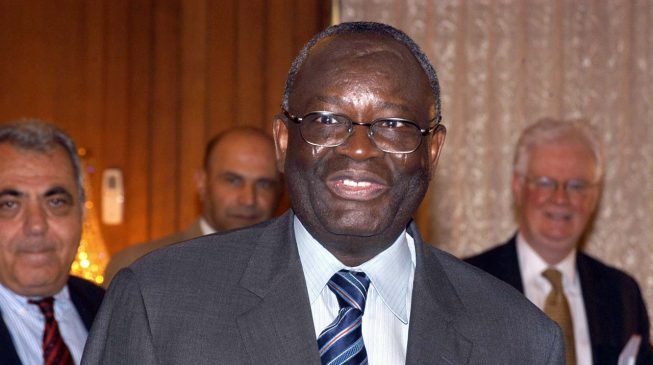

On May 12,President Muhammadu Buhari appointed Professor Ibrahim Agboola Gambari as his chief of staff, replacing Abba Kyari, who passed away on April 17. Professor Gambari’s predecessor, described by the newspaper, Daily Trust, as “de facto head of government”, was widely vilified. He was believed to have usurped the powers of a reticent and frail president and was held responsible for the real and perceived crimes of the administration, from human rights abuses to fostering an agenda of sectional domination. The late Abba Kyari definitely had a big impact on shaping economic policy; his daughter’s public tribute unwittingly reveals how he overrode the legally-backed and exclusive powers of the Nigerian Electricity Regulatory Commission (NERC) to influence electricity tariffs. The new chief of staff will wield enormous influence, given President Buhari’s well-known preference to delegate power. How will Professor Gambari use these powers in the sphere of economic policy making and what is the appropriate role of a chief of staff regarding economic policy-making in a Presidency?

“Who Is the Presidency?”

The question above should have been what is the role of the Presidency in policy development, had a former secretary to the government not posed the now famous question: “Who is the Presidency?”

His question confirmed to many Nigerians that in the Buhari Presidency, power is dispersed; the president is not always the unquestionable source of presidential orders. Rather than actively leading the coordination of ministers and the vast bureaucracies under them, President Buhari has, as a result of a mix of old age, personal preference and frailty, ceded the control of government to aides who only have to report to him. There has been a great latitude in determining the content, if not the overall direction of policy.

This will not change. The new chief of staff has been appointed to coordinate government for the president. This is why the role could be given only to an old ally that the president can really trust and who is deemed, in the estimation of President Buhari and his closest advisers, to have the required intellectual heft (preferably far in excess of the collective brainpower of the federal cabinet).

The Presidential Gate Under Gambari’s Watch: A Wider Funnel?

The expectation was that if someone like the Minister of Education, Adamu Adamu got the chief of staff job, the policy making process would have become more collegiate, with ministers and heads of agencies having more input. The late Abba Kyari, whom friends have invariably described as cerebral, despite very scant evidence, fancied himself a development policy guru. He had a great incentive to centralise policymaking. The late chief of staff had decidedly antiquated leftist economic views, which aligned with President Buhari’s perspective but contrasted completely with the more pragmatic views of ministers who understood and agreed to some of the reforms Nigeria had to implement to attract foreign exchange and investment in sectors such as power. The ministers understood where power laid and adjusted their views to the statist policy directives from Aso Rock to keep their jobs. A chief of staff less convinced of his own genius, would communicate and seek to clear collective viewpoints with President Buhari. At the very least, the President would be made aware of diverse viewpoints and the discretion over policy design and execution used more to advance collegiate viewpoints.

Considering that the professor has had a career in which negotiation and persuading others on the basis of evidence is a requisite skill, he could be more open to evaluating the evidence and advice presented by economists, specialists and expert advisers. He could be a wider funnel, collating these evidence and expert information and in turn presenting these to the president.

There is no evidence that President Buhari’s antipathy towards the free market and multilateral development institutions has changed. There is also no evidence that Professor Ibrahim Gambari, unlike the late Mr. Abba Kyari, shares these views. Will the new chief of staff therefore seek to lessen the influence of his principal’s worldview, which has had ghastly consequences, on economic policy?

A genuine academic, rather than a presumptuous dabbler and ideologue, the professor could be more conscious of the limits of his specialisation. Considering that the professor has had a career in which negotiation and persuading others on the basis of evidence is a requisite skill, he could be more open to evaluating the evidence and advice presented by economists, specialists and expert advisers. He could be a wider funnel, collating these evidence and expert information and in turn presenting these to the president.

But Professor Gambari could also choose not to be the adviser who presents unwanted evidence, seeing his job as strictly supporting and executing President Buhari’s views on policy. Afterall, some of the bold decisions that need to be taken, such as floating the naira or trimming the nation’s civil service, are reforms which will meet with public opposition. Those who seek power like Professor Gambari, a former lecturer who since the early 1980s has gotten a series of government appointments, are also keen to preserve it. Professor Gambari defended the annulment of the June 12, 1993 presidential election and the human rights abuses of the late General Abacha enthusiastically and perhaps a little beyond the call of duty, as the Nigerian ambassador to the United Nations.

The Urgent Need for a More Centralised and Professional Cabal

Professor Gambari can promote economic reforms and keep his job. He may even end up achieving the highly unlikely – securing for President Buhari a legacy of economic policy achievement. He may solve a problem, which the late Abba Kyari’s critics have neither recognised nor acknowledged – the extreme weakness of policy development, coordination and execution capacity of the Nigerian Presidency. Ministers, especially under former President Goodluck Jonathan, have been too free to carry on as they pleased. TO BE CONTINUED.

Arbiterz is a digital business magazine.

This article is originally published in full by Arbiterz.

END

Be the first to comment