In an attempt to show that she is still on course to win large numbers of seats from Labour in the north of England, Theresa May arrived in her Tory battlebus at an industrial park in South Kirkby, near Pontefract, last Thursday afternoon. This part of West Yorkshire is regarded as rock-solid Labour territory. A few miles down the road is Frickley and South Elmsall colliery, closed under a Conservative government in 1992. The bitterness lingers.

At the 2015 general election Labour won the Hemsworth constituency by a country mile. The message from May’s visit was supposed to encapsulate a sense of confidence and ambition that, from now on, the Tories represent the best future for these parts.

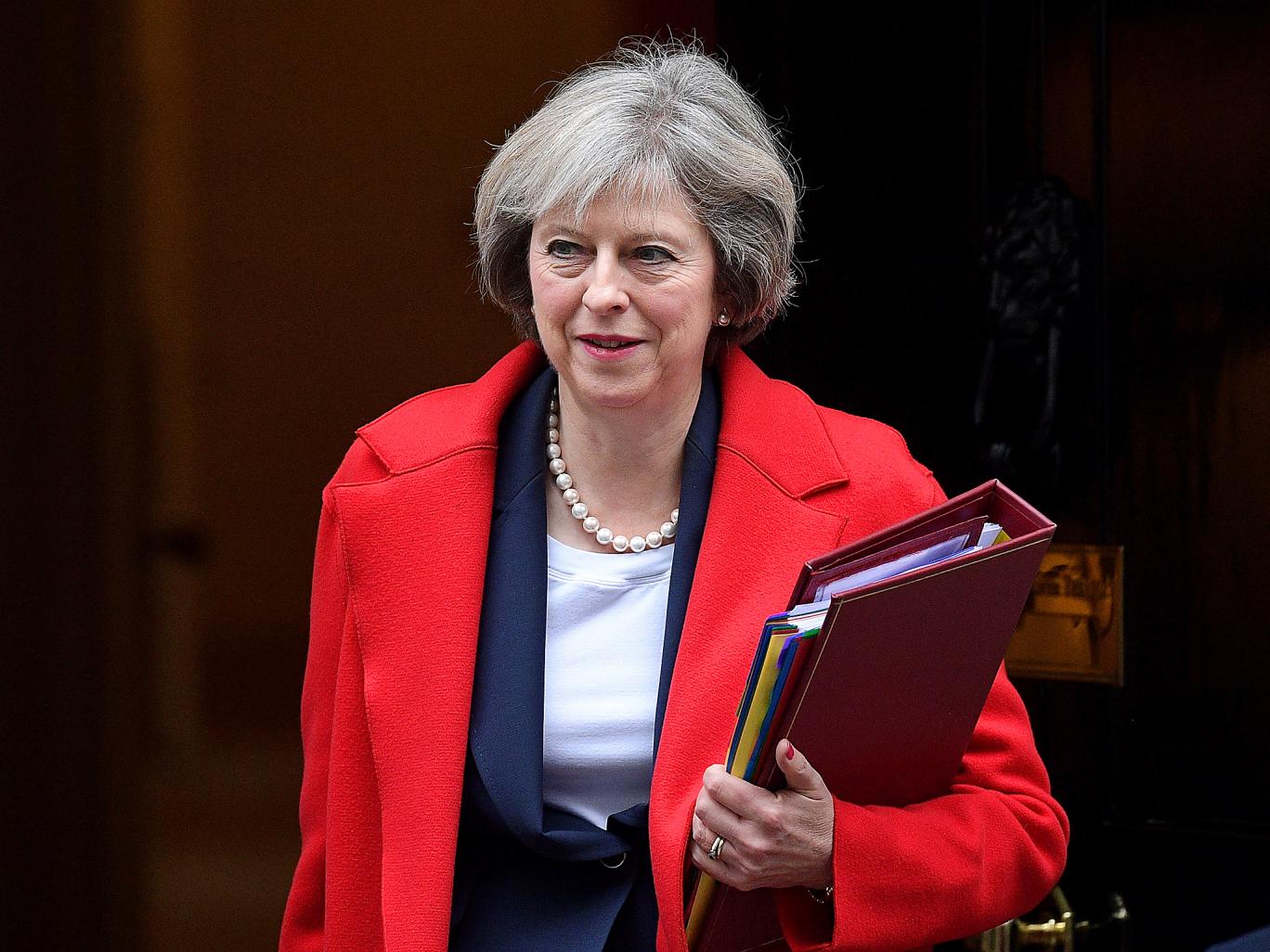

As the prime minister emerged from the bus which bears her name in giant letters, and was greeted by staff from a kitchen furniture factory called Ultima, a crowd outside its gates struck up an angry chorus just a few yards away. “Let’s make June the end of May!” they shouted. Labour banners were held aloft. It was not exactly the picture opportunity that the dozen or so Tory staff and spin doctors who had travelled north with the prime minister had wanted to create. Journalists and TV cameramen were ushered quickly inside.

But then nothing much has gone according to plan for Team May in the past fortnight. A campaign that started back in April with huge confidence – focused on the need for May’s strong leadership as the country approached Brexit negotiations – looked like it could turn into a coronation. The main questions were how big the Tory landslide, and the resulting humiliation for the hapless Jeremy Corbyn, would be. Then a policy U-turn on social care set in train a shift in the polls in favour of Labour, which has outperformed expectations, and the whole story has changed.

The May sheen has dulled as Corbyn has advanced in public esteem. The impression of competence and clarity of purpose that clung to the Tory leader has faded. The polls have tightened. One analysis by YouGov last week even predicted a hung parliament. If that is the outcome on 9 June, then May’s decision to hold a snap election will result in her going down in history as the shortestserving prime minister since Andrew Bonar Law in the early 1920s.

One of those outside Ultima’s gates was 33-year-old local truck driver Andrew Wilson, who voted Remain in the Brexit referendum. Across the constituency of Hemsworth there was a big majority for Leave, so Wilson is not one who simply follows the crowd. “The only reason people round here would have looked at May,” he said, “was because she was banging the Brexit drum. But despite that she won’t win round here. No chance. This is a place with roots.”

He declared himself “gobsmacked” that she came to Hemsworth at all, and said the parties’ manifestos showed where their respective priorities lie and who they care about. “If 50% of the Labour manifesto were implemented, it would be better than 100% of the Tory one. They offer nothing, nothing to working people. And then there was that dementia tax, all about people losing their homes to pay for care. That was terrible.”

The Tories are keen to give the impression that their strategy remains unchanged from day one of the campaign, while in reality it is being substantially rethought by the day. Only three-and-a-half weeks ago, May headed to the north-east claiming that she led the real party of working people by promoting a brazenly Red Tory message peppered with fierce anti-Corbyn rhetoric. “Across the country today, traditional Labour supporters are increasingly looking at what Jeremy Corbyn believes in and are appalled,” she said then. She would intervene in the market to protect working people by capping energy bills and guarding workers and their pensions from “unscrupulous bosses”. In policy terms, the party appeared to be moving left. In a presentational sense, the strategy focused around May herself (strong where Corbyn was painted as weak) to the point where local candidates, MPs and even senior ministers hardly got a look in when she visited their areas.

The Conservative party name was barely visible on much party literature and the battlebus, as if the prime minister wanted to persuade people to vote for her without clocking that it was for the Tories. For a time, it appeared to be working. But the May momentum seemed to go into reverse following the social care fiasco and, remarkably, the prime minister has found herself involved in a damage-limitation exercise rather than a victory procession.

Before she headed down the A1 to Pontefract on Thursday, the prime minister made a speech at a factory which makes mechanical diggers near Middlesbrough. There were signs, obvious and subtle, that campaign chief Lynton Crosby had ripped up the old hymn sheet and was effectively relaunching the whole show. May spoke to a handpicked audience and seemed to be aiming her message primarily at Ukip voters rather than traditional Labour ones. The target had changed. A prime minister who had backed Remain now described Brexit as something close to a panacea if it was handled right – as a “great national mission”, no less. She spoke of representing that “national spirit” necessary to deliver a good deal at a “great turning point in our national story”. There were no Red Tory themes, but instead a ramping up of patriotic anti-EU feeling, as she spelled out a vision of the country “set free from the shackles” of Brussels at last. Behind her on stage was a new campaign logo. Rather than “Theresa May. Strong and stable leadership”, it was “Theresa May and the Conservatives. A Brexit deal for a Bright Future”.

Yesterday there were signs of something approaching panic in Tory strategy when Sir Michael Fallon, the defence secretary, appeared to abandon his party’s previously non-committal line on tax for high-earners, saying this group would not be asked to pay more income tax if the Conservatives won. Within hours, May was insisting that nothing had changed.

The trick for Crosby in the campaign’s later stages is to recalibrate without being seen to do so too obviously. Internal party criticism of the campaign – not least for what some view as its anti-business tone – has grown behind the scenes. There is also a need to rebuild, somehow, the personal appeal of the prime minister. Where only a week or two ago she looked confident and competent, now she seems nervy and uncertain.

Advertisement

After May was outmanoeuvred on Wednesday by Corbyn, when he suddenly agreed to appear in a BBC debate with the other party leaders (which May had vowed not to take part in), she faced inevitable criticism that she was “running scared”, treating voters with contempt in an election she herself had called. The day after that difficult evening, her spin doctors ensured she was unusually available for journalists’ questions. On the battlebus she offered herself for short, on-the-record chats. But given a chance to offer voters more insight into who the real Theresa May was and how she thought, she gave little more than stock responses and evasion. When asked how this campaign “wobble” compared to previous ones she had known, she said: “Campaigns are all the same. You just work at them throughout the whole campaign. That’s what I do. I never predict election results.”

But why was Corbyn going down well with some voters? “I just get out there and campaign with my message,” was the unenlightening response.

For the prime minister and her team, these could not be more anxious days. Today’s Opinium/Observer poll puts the Tory lead at six points, down from 19 in mid-April. That is still, in all probability, enough to deliver the kind of majority that would vindicate May’s decision to go to the country. She and her party still enjoy a substantial lead on issues such as security and handling of both the economy and Brexit. May is also still favoured by more voters over Corbyn when it comes to who would make the best PM.

Polls in recent times have tended to overstate Labour strength, which offers some reassurance to the Tories as they narrow. But this is not going to be the triumphal coronation some envisaged. During the campaign, May has lost support among the public while Corbyn’s reputation has been enhanced. Opinium’s latest findings show 38% of voters view May more negatively than at the start of the campaign, against 21% who have a more positive view of her. When asked about Corbyn, 40% say their opinion of the Labour leader is more positive against 16% who say it is more negative.

In South Kirkby on Thursday, opinion had clearly swung decisively against her, even among one-time Conservative voters. Charles Elliott, 64, who used to vote Tory, said May held no appeal for him because her claim to be on the side of working people failed to convince. “She has soundbites, but no insight into how people work in places like this. OK, she is a vicar’s daughter. I am a vicar’s son, but she doesn’t have the feel of someone who understands other people.”

Jonathan Pile, a businessman, said she backtracks on everything, even the issue she says is the most important of all. “She is a liar on Brexit. How can you relate to someone who has U-turned like that?”

For Theresa May, a hoped-for smooth progress towards her own mandate has become a hair-raising rollercoaster ride.

END

Be the first to comment