Balmoral: “Located in Royal Deeside,” we learn from the royal family website, this gigantic granite folly is “one of two personal and private residences owned by The Royal Family, unlike the Royal Palaces, that belong to the Crown”. So, other than exceptionally cold, according to Cherie Blair – and described by one royal biographer as “gruesome, ugly and dull” – perfect for any member of that family in need of complete privacy.

As for a royal who might require a personal and private residence in which to avoid, for instance, being served with papers alleging the royal sexual abuse of a trafficked US minor, it’s hard to imagine anywhere better.

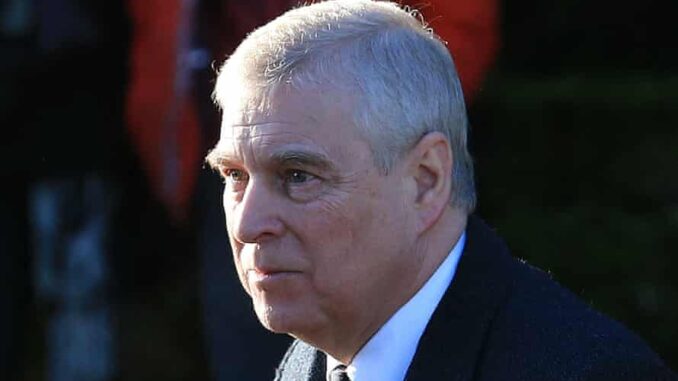

What is Prince Andrew up to inside Balmoral? Thanks to The Crown and various memorable accounts and photographs – one shows David Cameron almost succeeding in his bid to re-roof the place at a competitive rate – we can easily picture him huddled by a two-bar fire, struggling with a jigsaw puzzle or killing one of the symbolic wounded stags with which this vast estate abounds. At one time, you might even, in the picturesquely swirling mists, bump into an as-yet unprosecuted child sex predator; the late Jeffrey Epstein, Prince Andrew’s friend, was reportedly a guest there in 1999. Perhaps he felt at home with the dead animal heads and antlers, his own Manhattan home being, as Julie K Brown writes in Perversion of Justice, her impressive account of exposing Epstein’s crimes, “dark and ominous”. The interior featured individually framed glass eyeballs, with one room he called “the leather room” and another the “dungeon”.

It remains obscure, however, why the prince enjoyed staying with this charmless and sinister – even if you never spotted a succession of young girls – financial adviser who, when not being massaged, liked to share his dream of seeding a master race with his DNA. Although Epstein’s mysteriously acquired wealth was convenient when, in 2010 (after he had been jailed for soliciting sex with minors), Fergie needed a loan.

As for Balmoral today, even with attractions including his ex-wife and thousands of doomed grouse, Andrew surely can’t hide there for ever or not without addressing the civil lawsuit launched last week by Virginia Roberts Giuffre. The most recognisable alleged victim of Epstein’s sexual assaults and trafficking, she says she was sexually abused by the prince in 2001. After escaping a miserable home, foster and institutional care and imprisonment by a trafficker, Giuffre appears to have been the sort of isolated “character”, as Prince Charles calls struggling teenagers, that some of the best known royal charities were set up to support. Epstein liked to pose as a benefactor, varying threats and intimidation with promises to pay for college or to set up his victims with modelling careers.

Prince Charles makes it known that for Andrew, whose endurance of “slings and arrows” elicits his sympathy, there is now no return to public life. Since royal family life is routinely public, that could mean anything. Andrew is welcome, his name uncleared, at the semi-public retreat to Balmoral and presumably afterwards in his subsidised mansion on a crown estate. You wonder what he’d have to do to forfeit these signifiers of royal approval. Trade in horsemeat? Because a family brand so invested in children’s charities and whose image relies deeply on this connection is unlikely to escape contamination, as more details emerge, from Andrew’s closeness to a prolific paedophile and to that paedophile’s associate, Ghislaine Maxwell. Her trial, on charges of procuring girls for Epstein, is due this autumn.

Are they aware inside Balmoral of what Epstein, their former party guest, did to girls? Or just, as it increasingly appears, indifferent? In the United States, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology finally apologised, with resignations, for its shameful association with Epstein, and MIT had not, at least, formerly advertised itself as the saviour of the young and dispossessed: his prey.

From at least the time of Prince Philip, British royals have identified themselves as, especially, protectors of children and young people: an apolitical, attractive, largely amenable demographic that might grow up to feel loyal. If Diana is often portrayed, as with the new statue and the Diana award, as having a special vocation, the Duke of Edinburgh awards preceded her, followed by Charles’s Prince’s Trust, Prince Harry’s Sentebale, the Cambridges’ Place2be, Kate’s early childhood foundation and, according to her mythology, Sarah Ferguson’s work as a “philanthropist for children”. The Queen is patron of the Scouts and Princess Anne of Save the Children, which fights child trafficking. Charles last year appointed Katy Perry a British Asian Trust ambassador against the same crime. Were it not for the Giuffre lawsuit, there might last week have been more coverage of William’s support for another child-focused royal scheme, Future Forward, to “unlock the potential of young people”.

His uncle has previously dismissed, despite the photograph of him holding her side, Giuffre’s account of being trafficked to him when she was 17 – actually on the old side for Epstein. His preference, Brown reports, was for “waif-like prepubescent girls from troubled backgrounds who needed money and had little or no sexual experience”. Giuffre looked old enough to get into, for instance, Tramp, where the prince, in his catastrophic interview with Emily Maitlis, denied accompanying her.

Absurd as they were, Andrew’s assorted excuses and pizza alibi offered the royal family and its supporters an exculpatory narrative, to the point of allowing Harry to replace him – “recollections may vary” – as the official blood fabulist, bent on spoiling the Queen’s forthcoming jubilee. Andrew, in contrast, was restored to us this year, eulogising his father: “We’ve lost almost the grandfather of the nation.” Which makes him – what – the nation’s creepy uncle? Or worse?

The longer Andrew is silent on the Giuffre lawsuit, the more his immediate family may want to review, if only for consistency’s sake, its traditional concern for marginalised young people. Maybe old ones would be less trouble.

Catherine Bennett is an Observer columnist

END

Be the first to comment