The US’s departure has prompted a national sense of shame and a recognition there will be no victory in the ‘war on terror’

Ben Rhodes was a US deputy national security adviser in the Obama administration

oreign policy, for better or worse, is always an extension of a nation’s domestic politics. The arc of America’s war in Afghanistan is a testament to this reality – the story of a superpower that overreached, slowly came to terms with the limits of its capacity to shape events abroad, and withdrew in the wake of raging dysfunction at home. Viewed through this prism, President Joe Biden’s decisive yet chaotic withdrawal comes into focus.

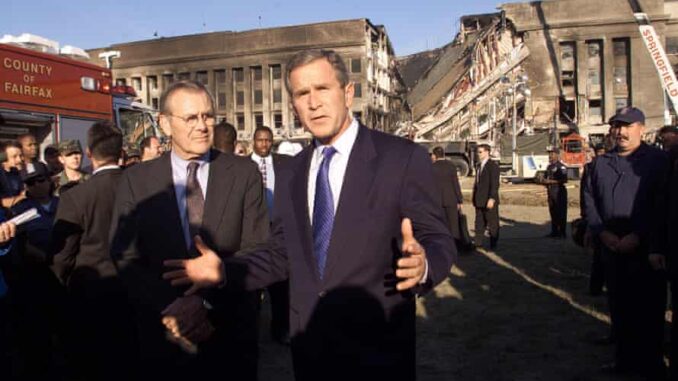

The story begins with trauma and hubris. On September 11 2001, American power was at its high-water mark. The globalisation of open markets, democratic governance, and the US-led international order had shaped the previous decade. The spectre of nuclear war had been lifted, the ideological debates of the 20th century settled. To Americans, mass violence was something that took place along the periphery of the post-cold war world. And then suddenly, the periphery struck the centres of American power, killing thousands.

Advertisement

As a young New Yorker, I saw a plane plough into the World Trade Center and the first tower fall. I smelled the air, acrid from burnt steel and death, for days afterwards. Like most Americans, I assumed my government would retaliate against the people who did this. But President George W Bush’s administration had larger ambitions. Speaking days after 9/11 to an audience that included the US Congress and British prime minister, Tony Blair, Bush declared: “Our war on terror begins with al-Qaida, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped, and defeated.”

Out of this trauma, the American public supported Bush’s declaration of a “war on terror” as a kind of blank slate, with details to be filled in by his administration. Most Americans were afraid, wanted to be protected, and were rooting for their government to succeed. Within weeks, Congress granted Bush open-ended powers to wage war, passed the Patriot Act, and set to work reconstructing the US national security apparatus. But rapidly toppling the Taliban and scattering al-Qaida did not meet the ambitions of Bush, who had likened this conflict to the second world war and the cold war. Instead of wiping out al-Qaida’s leadership (who escaped into Pakistan) and coming home, the Bush administration decided to build a new Afghan government and then promptly shifted its attention to Iraq – while tarring its political opponents as weak and unpatriotic. The die was cast.

The objectives of those early years – to defeat every terrorist group of global reach and also build liberal democracies in Afghanistan and Iraq – appear unfathomable with the distance of 20 years, but they were broadly accepted after September 11, in a climate of American hegemony and post-9/11 fervour. By 2009, when Bush’s presidency ended amid the ruins of Iraq and the wreckage of the global financial crisis, it had become clear that those objectives were unachievable, and that American hegemony itself was receding.

But the US national security establishment had been charged with achieving those objectives, and was therefore both invested in their completion and increasingly detached from shifting public opinion.

US marines at Camp Dwyer in Helmand province, 2009.

‘Paradoxically, the 2009-2011 troops surge in Afghanistan coupled diminished ambitions and increased resources.’ US marines at Camp Dwyer in Helmand province, 2009. Photograph: Manpreet Romana/AFP via Getty Images

The Obama presidency, which I was a part of for eight years, was a gradual reckoning with this reality. Paradoxically, the 2009-2011 troops surge in Afghanistan coupled diminished ambitions and increased resources: the US, Obama concluded, could not defeat the Taliban militarily, but needed to create time and space to defeat al-Qaida and build up an Afghan government to fight the Taliban. This conclusion reflected public opinion: in the politics of post-9/11, post-Iraq, post-financial crisis America, there was zero tolerance for terrorist attacks and zero appetite for nation building. This was the view that Biden, then vice-president, represented in the White House situation room – arguing against the surge on the grounds that we had to understand the limits of what could be achieved in Afghanistan.

By May 2011, the killing of Osama bin Laden removed what many Americans regarded as the original rationale for the war in Afghanistan, just as the surge was approaching its endpoints. At the same time that our counter-terrorism mission achieved its greatest success, the expansive new counter-insurgency campaign was proving far more difficult than promised, suggesting that Biden’s warnings had been prescient. In June 2011, the American drawdown began.

Obama’s downsized ambitions for the “war on terror” triggered harsh reactions from both the jingoistic right and the US national security establishment. For prominent military leaders, congressional hawks, and thinktank warriors who had set out to achieve these impossible objectives, Obama was insufficiently committed to the missions. To admit otherwise, you would have to accept that the mission itself was flawed – and that was a bridge too far for national security elites shaped by post-1989 American exceptionalism. For the Republican party, which had promised great victories in Iraq and Afghanistan, it was impossible to acknowledge there were any limits to our power; instead, it was easier to shift focus to other perceived threats to the US and American identity, which now came not just from “radical Islam”, but from any available Other – be it a black president or immigrants at the southern border.

As president, Donald Trump waged war against a shifting cast of enemies at home with far more gusto than he approached Afghanistan. For a time, he maintained an awkward detente with hawkish elements of the US establishment, signing off on a small surge in Afghanistan. His disregard for the Afghan people was initially manifest through increased civilian casualties. After he removed national security advisers like HR McMaster and John Bolton, it morphed into a deal with the Taliban that cut out the Afghan government and set a timeline to withdraw American troops. To the right, national security was tied up with white identity politics at home. To the left, terrorism was more evident in the Capitol insurrection than in distant lands. Trump’s withdrawal barely registered in US politics.

In this context, there was no way Biden was going to cancel Trump’s deal and extend America’s presence in Afghanistan. Having long doubted the capacity of the US military to reshape other countries, he was not going to continue a policy premised on that assumption. Given the existential threat to American democracy that clouded his transition into power, Biden presumably felt that the purpose of his presidency was to pursue policies responsive to restive public opinion – from a sweeping domestic agenda to a foreign policy for the middle class.

Biden’s decision, and the haste with which he carried it out, provoked a firestorm among much of the US national security establishment for several reasons. First, because Biden’s logic carried a rebuke of the more expansive aims of the post-9/11 project that had shaped the service, careers, and commentary of so many people. Second, because unlike Trump, Biden is a part of that establishment – the former chairman of the Senate foreign relations committee, a Washington fixture for decades. Biden’s top aides also come from that establishment. These are not illiberal isolationists. Instead, Biden and his team saw the war in Afghanistan as an impediment to dealing with other external threats: from a Russia waging an asymmetric war on western democracy, to a Chinese Communist party aiming to supplant it.

Most importantly, the abandonment of Afghans to the Taliban, and Biden’s occasionally callous rhetoric laying the blame on Afghan security forces, who had fought on the frontlines for years, evoked a sense of national shame – even if that emotion should apply to the entirety of the war, and not simply its end. Indeed, in the chaotic days of withdrawal, the predominant concerns in US politics often had little to do with Afghans. The evacuation of Americans, the danger of Islamic State Khorasan Province, and the loss of US service members eclipsed the gargantuan Afghan suffering. Overwhelming public support for Biden’s decision, though undercut by dissatisfaction with the process of withdrawal, confirmed Biden’s core instinct: the thing most Americans agree upon is that we went to Afghanistan to take out the people who did 9/11 and prevent further attacks, and it was past time to abandon the broader aims of post-9/11 foreign policy, no matter the subsequent humanitarian cost.

In short, Biden’s decision exposed the cavernous gap between the national security establishment and the public, and forced a recognition that there is going to be no victory in a “war on terror” too infused with the trauma and triumphalism of the immediate post-9/11 moment. Like many Americans, I found myself simultaneously supporting the core decision to withdraw and shuddering at its execution and consequences. As someone who worked in national security, I have to recognise the limits of how the US can shape other countries through military intervention. As someone who has participated in American politics, I have to acknowledge that a country confronting virulent ethno-nationalism at home is ill-suited to build nations abroad. But as a human being, I have to confront how we let the Afghan people down, and how allies like Britain, who stood by us after 9/11, must feel in seeing how it all ended.

It is a cruel irony that this is the second time the US has lost interest in Afghanistan. The first time was in the 1990s, after much of the mujahideen we supported to defeat the Soviets evolved into dangerous extremists, plunged the country into civil war, and led to Taliban rule.

The final verdict on Biden’s decision will depend on whether the US can truly end the era that began with 9/11 – including the mindset that measures our credibility through the use of military force and pursues security through partnerships with autocrats. Can we learn from our history and forge a new approach to the rest of the world – one that is sustainable, consistent, and responsive to the people we set out to help; that prioritises existential issues like the fight against the climate crisis and genuine advocacy for the universal values America claims to support?

A good place to start would be fighting at home to strengthen our multiracial and multi-ethnic democracy, which must be the foundation of America’s global influence. That effort must include welcoming as many Afghan refugees as we can. What the US needs at the end of the 9/11 era – more than any particular policy, or assertion that “America is back” – is to pursue the kind of politics that makes us a country that cares more about the lives of other human beings like the Afghans we left behind, and expresses that concern in ways other than waging war.

Ben Rhodes is author of After the Fall: Being American in the World We Made. He served as a deputy national security adviser for Barack Obama from 2009-2017

END

Be the first to comment