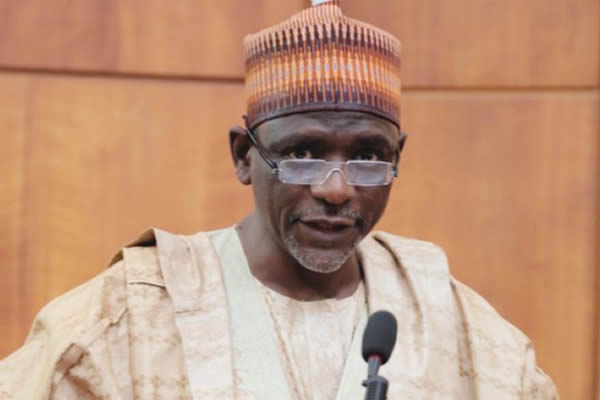

Recently, the Minister of Education, Mallam Adamu Adamu, disclosed that the number of out-of-school children (OOSC) in the country had dropped from 10.5 million to 8.6 million in the last three years. According to him, “When President Muhammadu Buhari came into power in 2015, UNICEF said out-of-school children in Nigeria were about 10.5 million. But I want to tell Nigerians that with the effort of this president, especially with the school feeding programme, it dropped from 10.5 million to 8.6 million as at last year.” While the difference in figures is understandable, there is nothing to cheer in a single Nigerian child, not to talk of millions of children, being out of school. The current government may have brought the figure down but the disgrace remains monumental.

The problem of OOSC is global as UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS 2014) stated that worldwide, nearly 58 million children of primary school age were not enrolled in school despite global initiatives dedicated to achieving universal primary education. Among these world’s OOSC, over two-thirds are in Sub-Saharan Africa and South and West Asia.

In finding solutions, experts diagnosed the problems leading to OOSC and attribute the prevalence in Sub-Saharan Africa to a variety of supply and demand side barriers. They argue that children’s poor access to education may be occasioned by inadequate number of qualified teachers, materials and schools, particularly for children in remote areas, children living with disabilities, children in IDP camps and ethno-linguistic minorities. On the demand side, they opine that poor demand for education leading to exclusion from school may be driven by misperceptions about the benefits of schooling and or poor quality of education

Even so, the assertion of Adamu is doubtful because the source of the figures and their veracity were not made known. The claimed improvement in Nigeria, attributed mainly to the school feeding programme, discounts the efforts of the various states and local governments to promote children education and, therefore, renders the figure even more suspect. For instance, the administration of Governor Emmanuel Uduaghan changed the face of education in Delta State through some educational policies and one of such policies was the Delta Education Marshals (DEM) which has been replicated in some states of the federation.

The DEM policy was formulated by the state government then to eradicate ‘street culture’ and create what was called ‘learning culture’. The educational policy was enunciated to support the development of learning in young people of school age in the state. The EduMarshals were given specific mandates which included the detection and prevention of truancy among students; the apprehension of school age child hawking or selling in stores or shops during school hours; maintenance of school hours surveillance and arrest, detention and investigation and/or returning or registering any person of school age found outside school premises during school hours. Other functions of the EduMarshals are the provision of intelligence to relevant ministries, police and stakeholders on any matters relating to a child, to make a child under 18 years of age to attend school or learn a trade (skills acquisition) and to ensure that the streets of Delta State are free of children during school hours.

Similarly, there is the Osun State Education Marshalls, constituted to help curb all forms of indiscipline and moral decadence among pupils and staff of public schools in the State. The Oyo State government’s variant codenamed “Education Monitoring Marshalls” was introduced to raise more disciplined school children as the special tax force is empowered to arrest and discipline students caught wandering out of school premises during school hours, aimed at changing students’ attitude positively towards learning. In a related development, Governor Aminu Waziri Tambuwal of Sokoto State, while flagging off an advocacy campaign to boost school enrolment for the eastern part of the state in Durbawa village of Wurno Local Government Area, warned that parents in the state would now face appropriate sanctions in accordance with the laws of the state for refusing to send their children to school.

Furthermore, some state governments have developed a culture of continuously improving the quality of education from primary to tertiary levels through the provision of state-of-the-art infrastructural facilities, capacity building for teachers and many other programmes to to promote effective teaching and learning in the schools.

So, at the moment in Nigeria and across various levels of government, it is obvious that enrolling OOSC is now seen not only as a moral and legal obligation but a productive investment that is worthwhile, and it is being given attention in line with the 2003 Child Rights Act, which recognises access to basic education as part of the rights of a child. Also, from the interventions by various states, it is obvious that there is no single measure to drive demand for children school enrolment. The solution lies in multi-level interventions and investments in primary education. Therefore, people holding the reins in Nigerians should not speak anecdotally on the issue of OOSC! The country needs serious data gathering to deal with its problems. Once again, with the aforementioned efforts in the states, the picture of OOSC may not be as bad as the minister painted. But whether it is more or less is not important. Nigeria should strive towards zero tolerance for such a future-damaging phenomenon as out-of- school-children.

END

Be the first to comment