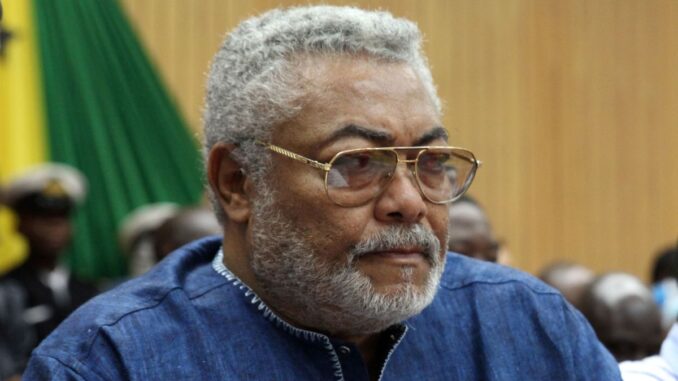

He was, no doubt, one of the most controversial leaders Africa ever produced. But Jerry John Rawlings, Ghana’s former military officer, and politician were nevertheless one of the most successful leaders. His popularity was in spite of his fearsome reputation as an officer who summarily executed Ghanaians, including three preceding Heads of State, all on account of ridding the country of the cankerworm of corruption. His methods were less than the minimum required for due process of modern times. But he produced results that ultimately set Ghana on a solid footing for real development; and he remained popular for it till death.

Rawlings who died at 73 on November 12, 2020, of COVID-19 related causes, was articulate and urbane as the former head of state and president of Ghana. Despite a life dogged by controversy and high-handedness, he was a quintessential statesman; an African reformist that made an enviable mark in history.

His death took away from Africa and the black race the scarce resource of quality leadership. In a crowd of opportunistic, self-serving former heads of state, Rawlings was one of the few authentic voices of strategic thinking and motivation for national leadership. In an age when it is fashionable for many African political leaders to relish their positions as puppets of more powerful nations, to the disadvantage of their countries, Rawlings flourished as a triton among the minnows, deploying energy, intellect, and skill towards a reconfigured inward-looking Africa.

Born in Accra, Ghana, as Jerry Rawlings John on June 22, 1947, to Victoria Agbotui, an Ewe mother from Keta, in the Volta Region of Ghana, and a Scottish father James Ramsey John, who was a chemist, Rawlings attended Achimota School, from where he graduated in 1967. That same year he joined the Ghana Air Force and got commissioned two years later as Pilot Officer. Rawlings earned laurels as the best cadet in aerobatics and later rose through the ranks to become Flight Lieutenant in 1978. In one interview he revealed how his military service exposed him to the biting poverty of the masses, and in contrast, the indiscipline and low public morale, inflicted by corruption in the country’s highest military ruling body, the Supreme Military Council.

Rawlings came to the limelight when, having escaped from custody over a failed coup plot, he and a group of junior officers formed the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC) that ruled Ghana for 112 days, in a brazen attempt to dramatically overturn Ghana’s seemingly incurable corrupt leadership and colonial dependency. This radical purging of Ghana’s corrupt leadership saw the execution by firing squad of eight top military officers including three former Ghanaian heads of state: Ignatius Acheampong, Fred Akuffo, and Akwasi Afrifa.

Hardened by an uncanny sense of justice reinforced by his association with leftist intellectuals, Rawlings set off on a “house cleaning” mission across Ghana. He later handed over peacefully to a democratically elected Hilla Limann in 1979, only to overthrow that regime two years later through another coup d’etat. For the next 20 years from December 31, 1981, he ruled Ghana as head of state under the revolutionary movement of the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), and then as the president under the National Commission on Democracy (NCD) from January 7, 1993, to January 7, 2001, when he was succeeded by John Kufuor.

Rawlings’ blatant extermination of corrupt military leaders sent a strong signal of zero tolerance for indiscipline and corruption, and this set Ghana on a slow but steady course of economic recovery and political stability. Although his motives were often obscure, he carried out controversial economic reforms that empowered rural dwellers and founded Ghana’s future industrialisation. In the course of policies and actions, Rawlings stepped on toes. Kindly, however, history remembers him for getting things done.

Not unexpectedly, Rawlings endured accusations of grandiloquence and unjustified posturing when his leadership is viewed against his human rights records. For instance, while he made sure the Ghana refineries worked, he went hard by executing 10 refinery workers to stop future failure of refineries. Besides, he tended to intimidate and confound his interviewers and discussants, just as he was economical with the truth on some critical facts. He accused Nigeria of expelling Ghanaians to destabilise his government, while not admitting that Ghana actually expelled Nigerians first.

Rawlings spent his post-presidency years delivering lectures at conferences and universities and acting as special envoys for the African Union, amongst other volunteering projects. A recipient of numerous awards, Rawlings was married to Nana Konadu Agyeman with whom he had four children. He died on November 12, 2020, barely two months after the death of his own mother.

African leaders should harvest the positive qualities of this uncommon leader as a model of their political and social engagements, rather than revel in fleeting customary condolences. Rawlings, as a youth in the Ghanaian Air Force, had a nationalistic spirit to embark on radical problem solving for his country. Young people need to be encouraged to be patriotic and to solve problems. True leaders get things done by breaking out of the cycle of routine and the protectionism of bureaucracy. Barring his excesses and foibles, that is the lesson of progress taught by Jerry John Rawlings.

END

Be the first to comment