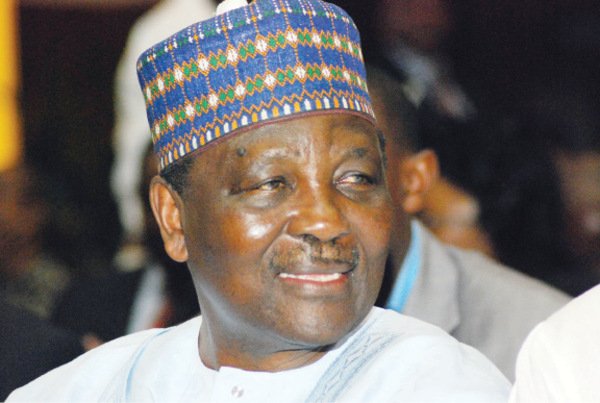

In the tumultuous and chequered history of the Nigerian nation, the name of General Yakubu ‘Jack’ Gowon, head of state and commander-in-chief of the Nigerian Armed Forces, from August 1 1966 to July 29, 1975, serves as a reference point in our quest for national unity and reconciliation especially after the fratricidal civil war of 1967 to 1970. War-time national leaders are invariably judged by how well or otherwise they managed the conflict and their role in post-war reconstruction and politics.

Any evaluation of General Gowon’s contribution therefore to the Nigerian project must encapsulate the pre-, the actual period of fighting and post-war activities of this warm and affable gentleman who steered the affairs of the country for nine long years from when he was barely 31years of age.

How did this enigma of a general happen on the Nigerian political stage and national history? For what do we remember, how shall we remember retired General Gowon in the reconstruction and/or documentation of history? As one of the early beneficiaries of a forceful overthrow of governments that became the bane of Africa, what was his contribution to that ugly spectacle in our national history? How well did he handle the pre-war conflict and the three R’s, which he declared when the Biafran secession ended? How do we judge him for reneging on his promise to return to civilian rule in 1976? What were his strengths and weaknesses in managing the ill-fated discovery of oil and petrodollars, and what became known as the ‘Dutch disease?’ Since leaving power in 1975, how has he fared as a private citizen? How does he stand in the estimation of Nigerians in comparison with other previous military dictators?

Born October 19, 1934, the young Gowon attended Government College, Wusasa and ultimately ended up in the military after training in Royal Military Academy Sandhurst from 1955 to 1956. He also attended Staff College, Camberley in 1962. If he had pursued a military career only, perhaps he would not have featured in the political history of Nigeria. But fate thrust the reins of leadership on him after the counter-coup of July 29, 1966. Then a Lt. Col., he emerged as Head of State because he was seen as a moderate officer who had the temper to manage the political affairs of the country in those tension-soaked years.

Less than a year after he took office as Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces, the unity of the country was threatened by the secession of the Eastern Region because, in the words of his arch-rival Col. Odumegwu Ojukwu, ‘‘the security of Igbo lives and property could no longer be guaranteed under Nigeria as constituted.’’ In May 1967, hostilities broke out between the Federal side and the Republic of Biafra. What Gowon referred to as ‘‘police action,’’ dragged on for 30 long months in which about three million Igbo people died.

The war tested the managerial capacity of General Gowon. Although he declared that the offensive against the Biafran enclave was a ‘‘police action,’’ the hard fact was that the war became bloody and hunger was deployed as a weapon against the secessionists. The field commanders seemed to have a different view of how to prosecute the war. Gowon’s gentle disposition did not filter down to the brutal realities of the genocidal conflict. When General Effiong surrendered in January 1970 Gowon pronounced the three Rs- Reconciliation, Reconstruction, Rehabilitation – as a way of erasing the horrible scars of the war. History would credit Gowon with the declaration though the Igbo would argue that if the three Rs had been effective, there would have been no MASSOB or IPOB nearly 50 years later.

It is, therefore, indisputable that the issues, which led to the civil war, are still unresolved. Gowon’s honest intentions were never in doubt, but the hawkish forces around him, right from the countercoup of July 1966, would never let up. And the consequences are still glaring in the polity today.

Gowon had promised to return the country to civil rule by 1976. When he reneged on the promise stating that politicians had not learned their lessons, Nigerians were restive. This was one of the reasons the coup plotters advanced for the Gowon’s overthrow on July 29, 1975. Gowon quickly took to life as a private citizen in the United Kingdom where he settled down. He read up to PhD level and remained in the shadows of public life. His name was to surge again in the Nigerian public space when Lt. Col. Buka Dimka implicated him in the aborted military coup of February 1976 that recorded the brutal assassination of General Murtala Mohammed. Gowon was stripped of his title and declared a wanted man. In the years that followed, he was pardoned and he finally returned to Nigeria.

END

Be the first to comment