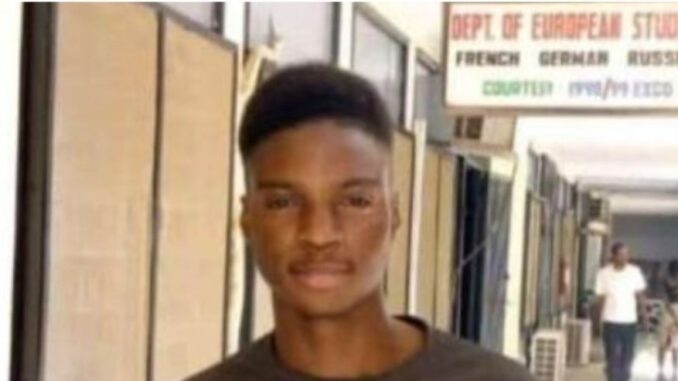

A promising 300-level undergraduate of the University of Ibadan died recently in a cruel manner in an avoidable factory accident in Ibadan, the Oyo State capital. The victim, Richard Gbadebo, lost his life after slipping into a soap-making machine at a factory owned by Henkel Nigeria Limited, producers of laundry and homecare products. The 21-year-old was engaged in a holiday job due to the closure of schools occasioned by the COVID-19 pandemic. The Nigerian Factory Act prescribes health, safety and welfare regulations for workers, including penalties for violation of the provisions. Specially, it states, “Every dangerous part of any machinery, other than prime movers and transmission machinery, shall be securely fenced, unless it is in such a position or of such construction as to be as safe to every person employed or working on the premises, as it would be if securely fenced, provided that, in so far as the safety of a dangerous part of any machinery cannot by reason of the nature of the operation be secured by means of a fixed guard, the requirements of this subsection shall be deemed to have been complied with if a device is provided, which in the opinion of the Director of Factories satisfactorily protects the operator or other persons from coming into contact with that part.”

Obviously, the provisions of the Act are observed in the breach by many. Factory workers have one of the highest rates of workplace injury and death because of their exposure to heavy machinery, toxic and flammable chemicals, extreme temperatures, and other potential dangers. This death is tear-jerking as reports noted that Gbadebo, who worked as an operator at the firm, was on night duty on the day of the incident when he fell into the machine and other workers were not aware of the tragedy until blood started gushing out from the machine’s other end. Gbadebo’s death adds to the list of needless deaths lost to criminal laxity in regulation, monitoring and enforcement of safety rules in workplaces. This is a tragic and pointless death.

Gbadebo would be alive today if the government had displayed the requisite leadership by insisting on compliance with standard safety measures long before now. Many states in Nigeria are guilty of weak enforcement of the safety, health and welfare provisions on factories. This explains why many owners of industries are as bold as brass whenever preventable disasters occur. Compensating the family of the late Gbadebo is appropriate, though doing so would not restore him to life. The Oyo State Government should, however, use his death to fix the rot in factory administration in the state to avoid a recurrence.

The high rate of deaths from workplace accidents in the country is troubling, exposing the unchecked operations of expatriate factory owners especially who have been exploiting the country’s lax enforcement system and labour laws. In 2002 at a plastic factory in Ikorodu owned by some Asians, dozens of workers were roasted to death having been denied multiple exit points and unable to escape when the fire broke. In the most degrading manner, the slave masters locked them in while they worked their hearts and souls for a pittance. Also, during the COVID-19 lockdown in July, Indian owners of a rice processing company in the commercial city of Kano locked in hundreds of workers to work before they were rescued by the police following a tip-off.

In November 2019, one 50-year-old Sunday Usenobong, an employee of an Ikorodu, Lagos-based firm, reportedly fell into a melting pot while operating the company’s machine. He died on the spot and homicide detectives visited the scene and evacuated the corpse to a public morgue for autopsy. Also, one Femi Olatunde, while operating a moulding machine at an Ikeja-based company, reportedly got trapped in the machine and died on the spot. Several hapless workers had similarly lost their lives to avoidable factory accidents, while others survived but emerged to be confined to prostheses. Some executives’ negligence, fuelled by greedy expatriates conspiring with willing Nigerian collaborators, pitifully altered their natural features.

Many factories and private firms, including those owned by expatriates, violate safety rules and regulations with impunity. This, many noted, emboldened the factory owners who take advantage of the alarming unemployment rate in the country to execute their despicable acts with impunity. The African Development Bank noted last year that Nigeria’s unemployment rate was frightening. It has further worsened with the COVID-19 challenges with the recent figure released by the National Bureau of Statistics as of the second quarter of 2020 being 27.1%.

Industrial accidents cannot be eliminated, but can be minimised. Workplace experts advise every office and small business can and should put in place preventive safety programmes, which can pinpoint specific hazards in the workplace and give management a detailed evaluation with tips for improvement. Industrial accidents can be prevented or reduced especially if relevant authorities and safety agencies transparently ensure compliance with safety rules. For this, the Federal Government ratified the International Labour Organisation Convention No. 155 on Occupational Safety, Health and Working Environment in 1994 and charged the Federal Ministry of Labour with its implementation.

There cannot be a price tag for careless and unnecessary deaths. The organised labour movement should always be persistent and genuinely demand efficient and transparent regulations from relevant agencies to rid the country of killer factories. It is not enough to demand better wages when workers’ occupational safety and health are below global standards. This is one of the best ways to give the Nigerian worker a sense of safety.

END

Be the first to comment