VICE-PRESIDENT Yemi Osinbajo has reignited the debate about the failure of the government to sweep away the systemic sleaze in our national life. At the 2018 Nigerian Economic Summit, Osinbajo yet again decried the endemic corruption in the public service. This has undermined development and made the country a butt of jokes. Regardless of this, there is no bold strategy yet from the Muhammadu Buhari administration to flush out the poison from the system.

Grilled on his experiences, the Vice-President stated that his biggest surprise in office was the corrosive corruption in the public service. He disentangled the toxic web of grand corruption from other forms of corruption. “Grand corruption is, in our context, where money is taken directly from the treasury and is simply diverted to private use and that is one of the most shocking types of corruption,” he explained. This occurred most brazenly during the immediate past administration.

Osinbajo’s reminder captures the rot in Nigeria’s public service, but it is neither surprising nor shocking as he stated. Corruption has become a way of life in Nigeria. With oil money flowing in, those entrusted with power stole the country’s resources with reckless abandon. Buhari told a global audience in July 2015 that public office holders stole $150 billion of Nigeria’s oil wealth in the 10 years to 2015. Since 2007, a coterie of former state governors, whose tenure ended that year, has been on trial for fleecing the public till. Shamelessly, they are prancing about. This is sordid.

Unfortunately, this has left Nigeria’s reputation in tatters. Ahead of an anti-corruption summit in London in 2016, a former British Prime Minister, David Cameron, described Nigeria as “one of the fantastically corrupt” countries of the world. Nigeria’s rating by Transparency International, the global anti-corruption watchdog, depicts the decadence. Nigeria ranked 148th out of 180 countries in the 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index, with a score of 28 out of 100. It scored 27 in 2012, 25 in 2013 and 27 in 2014. In effect, nothing has changed.

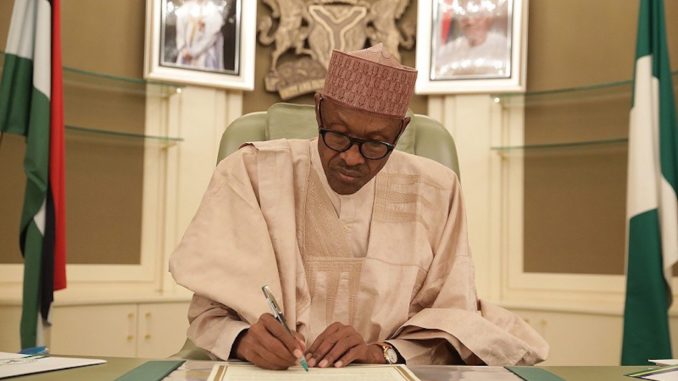

In fairness, the Buhari administration started out with good intentions to combat graft. After a series of exposés of grand cases of corruption, several suspects were put on trial. The trial of Sambo Dasuki for allegedly sharing out $2.1 billion that was allocated to buy arms to fight Boko Haram headlined the rot. The trial of ex-ministers, who allegedly received bribes to compromise the 2015 elections, had also elicited hope.

Similarly, State Security Service officers raided the homes of judges linked to corruption in 2016. Government later introduced the whistle-blower policy. In return for a fraction, informants exposed how officials stashed away their loot in different locations. The government made the right noises about the Voluntary Assets and Income Declaration Scheme, meant to bring in tax revenue and penalise tax evaders. All this was prematurely applauded.

In reality, nothing has changed. This is incongruous with Buhari’s 2015 campaign promise to stamp out of corruption if elected. Osinbajo blames the subdued results in part on the judiciary. The truth, however, is that the Buhari anti-corruption juggernaut has run out of steam. In a way, it is its own worst enemy. The cases of Babachir Lawal, Ayo Oke and Abdulrasheed Maina, which happened on Buhari’s watch, define the double standards in the administration’s anti-graft crusade. To tame corruption, Buhari should use these cases to show that there are no sacred cows around him.

However, the biggest obstacle in the Buhari government’s fight against sleaze is the lack of strategy. The security agencies bicker openly, as seen in the clash between the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission and SSS agents when the former wanted to arrest two former SSS DGs.

There is also the need to adopt cutting-edge technology in preventing and detecting financial infractions. After the 2009 expenses scandal over refunds for housing and transport in its parliament, the British Government swiftly established the Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority tasked with the duty of monitoring the parliamentarians. The IPSA created a website, where details of all the allowances and activities of every MP could be accessed at the touch of a button. According to the British Home Office, Britain tackles graft in part with its five-year anti-corruption strategy, the latest of which is running from 2017 to 2022.

Without a defined strategy, Buhari’s war against sleaze remains a non-starter. Without exception, all those who have soiled their hands – whether in the President’s inner circle or in the opposition – must be brought to book. Government should identify incorruptible judges in the system and saddle them with these cases. To quicken the pace of justice delivery, it could establish special courts to try corruption cases, and faithfully implement the Administration of Criminal Justice Act, which is a landmark enactment in 2015.

END

Be the first to comment