Five years ago, Kelly Sutton, a 22-year-old software engineer from Brooklyn, got rid of all of his possessions except for his laptop, iPad, Amazon Kindle, two external hard drives, “a few” clothes and sheets for a mattress that was left in his newly rented apartment. “I think cutting down on physical commodities in general might be a trend of my generation – cutting down on physical commodities that can be replaced by digital counterparts,” he said on his website CultofLess.com. In the interim, Sutton’s website has disappeared from cyberspace, which makes sense: after all, if you think about it, what is a website but yet another degrading thing, a means of shackling us to this vain world of folly and delusion?

Just possibly, Britain has joined this new puritan movement. Consumers here spent 26% of their total household budgets buying physical goods in the early part of the last decade. This declined to about 21% by 2014. Indeed, this week, the Office for National Statistics reported that the amount of material consumed in the UK has fallen from a peak of 889.9m tonnes in 2001 (15.1 tonnes per person) to 659.1m tonnes (10.3 tonnes per person) in 2013. Material consumption was lowest in 2011, at 642.0m tonnes (10.1 tonnes per person).

Why is this happening? Certainly, the rise of digital media has allowed us to stop cluttering our homes with DVD box sets, books and CDs. Another explanation involves the “peak curtains” hypothesis. Essentially, it posits that we have got enough things in our homes, thanks very much. It was set out earlier this year by Ikea’s head of sustainability, Steve Howard, at a Guardian Sustainable Business debate. “If we look on a global basis, in the west we have probably hit peak stuff. We talk about peak oil. I’d say we’ve hit peak red meat, peak sugar, peak stuff … peak home furnishings.”

Incredibly, the corollary of his argument was not that Ikea was finished. Rather, Howard reckoned Ikea was on course to almost double sales by 2020. How? “We will be increasingly building a circular Ikea, where you can repair and recycle products,” Howard said. Please no! I’ve spent much of my life crying over a hot Ikea allen key with tears staining a Swedish-language assembly document; now they want me to repair their flat-packed instruments of Beelzebub – sorry, I mean, cool, minimalist Scandinavian stuff – too? Not even Dante could concoct a circle of hell so cruel.

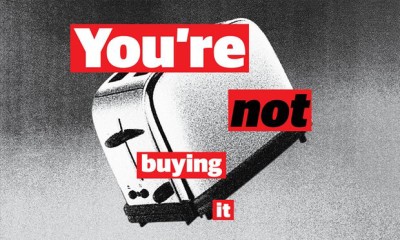

Howard’s argument trades on a mounting revulsion for acquiring physical consumer goods – be they Billy bookcases, ostensibly must-have Nespresso machines or state-of-the-art humidors. Why? “Materialism is making millions of us feel joyless, anxious and, even worse, depressed,” argues the futurist and journalist James Wallman. In his 2013 book Stuffocation: Living More with Less, Wallman strove to offer a cure to the disease the psychologist Oliver James had called affluenza in his 2007 book of the same name. Affluenza was a virus James reckoned was spreading virulently because it feeds on itself. When you try to make yourself feel better by buying a car, for instance, you make yourself feel worse, which makes you want to buy more things.

One way Wallman suggested we could escape from that endless cycle of misery was to focus on having nice experiences instead of on acquiring more stuff. He argued that “experiences are more likely to lead to happiness”. That shift from consumption to what he called “experientialism” is certainly a trend that thrives on social media. Think of it this way: instead of putting pictures of your newly acquired Triumph Bonneville on Instagram for your followers to like or diss, you post snaps of your walking tour through the Andes. What is the significant difference between the two? “Experiences are more likely to make us happy because we are less likely to get bored of them,” argued Wallman, who clearly has never waded for miles hip-deep in Weston-super-Mare mud at low tide. “We’re more likely to see them with rose-tinted glasses, more likely to think of them as part of who we are, and because they are more likely to bring us closer to other people, and are harder to compare.”

Yet there is more to the reduction in the consumption of stuff than its replacement by the experientialism Wallman trumpets. When Vivienne Westwood launched her autumn collection in 2010, she suggested we should not buy new clothes for six months, which must have left her sales people wringing their hands every bit as much as Steve Howard’s colleagues. Or maybe not: “My message is: choose well and buy less,” she said then – as if to suggest you should buy one Westwood dress rather than filling Primark trolleys regularly.

That sort of buy-less philosophy is echoed in the online shop Buy Me Once. It offers Patagonia brand coats, leggings and shirts that come with a lifetime guarantee; Tweezerman tweezers that you can send back to be sharpened and realigned; teddy bears that can be returned and repaired in a bear hospital; and Le Creuset dutch ovens that carry lifetime guarantees.

Only one problem: as with Westwood’s couture, the stuff on Buy Me Once isn’t cheap, wrote Madeleine Somerville in the Guardian last month. “It would be ignorant to assume that it’s pure evil that fuels the cycle of buying cheap crap that breaks: it’s not. For many, it’s the fact that coming up with $15 to replace an item every year is far more feasible than coming up with $100 to invest in something that will last a lifetime.” The buy-less philosophy as cure for affluenza is itself a luxury product.

This week’s ONS report, nonetheless, notes a shift to what it calls a circular economy “whereby we move from a ‘take-make-dispose’ approach towards ‘recycle-repair-reuse’”. We are increasingly nudged towards such reductions in consumption, and to mend rather than end. Last year, for instance, the French government began forcing manufacturers to tell consumers how long their appliances will last. French companies will also have to inform consumers how long spare parts for their products will be available, or risk a fine of up to €15,000 (£11,000). The aim is to help to combat “planned obsolescence” – the practice of designing products with restricted life spans to ensure consumers will buy more. You know the kind of thing: you have to buy a new electric toothbrush because the batteries can’t be replaced.

What was appealing about this decree was that, for once, government was standing up to big business and recognising that corporations often design their products to fail. In 1921, for example, the Phoebus cartel created light bulbs that would break after 1,000 hours instead of providing the 1,500-2,000 hours previous bulbs managed. Aldous Huxley’s nightmare of ending-is-better-than-mending consumption had been realised a decade before he imagined it in 1932’s Brave New World.

And then there was the recent news that the city of Hamburg had banned disposable coffee pods, along with bottled water and beer, chlorine-based cleaning products, air freshener, plastic plates and cutlery as part of a drive to reduce environmental waste. “The capsules can’t be recycled easily because they are often made of a mixture of plastic and aluminium,” said spokesman Jan Dube. “It’s six grammes of coffee in three grammes of packaging. We in Hamburg thought that these shouldn’t be bought with taxpayers’ money.” If material consumption is falling, one reason is because initiatives such as these make us reflect on what we are consuming and the extent to which it can be recycled.

Another official nudge to reducing consumption came in 2008, when then prime minister Gordon Brown argued “unnecessary” food purchases were contributing to price rises. At the time, a government study revealed that the UK wasted 4m tonnes of food every year, adding £420 a year to a family’s shopping bills. If there has been a fall in food waste since, it may be due to such nudges – appeals, not just to great environmental responsibility, but to self interest. Recently, for example, Recycle for Wales called on householders to dispose of food waste in their food bins rather than putting it in black bin bags – and sweetened the proposal by adding that “recycling 36 used tea bags creates enough electricity to power a TV for 80 minutes – enough time to watch Wales play in both halves of a Six Nations game”.

But the fall in material consumption is not just due to changes in consumer behaviour, argues Chris Goodall, businessman and author of books on climate change. “The root cause is a mixture of, yes, digitalisation, but also that western countries – and possibly China as well – have now got the capital stock they need to operate a modern economy. We are using less material to make roads, build buildings and other forms of infrastructure. Broadly speaking, we each need about 12 tonnes of stock of steel to give us a modern lifestyle – obviously, much of this is in the form of public infrastructure. We all have washing machines now. This means a reduced demand for metals and building materials overall.”

What’s more, Goodall argues, modern technology is helping us get more efficient. “The world is seeing better and more targeted use of things such as fertiliser and water. Machines are getting smaller and lighter.”

Machines are not the only things that are getting smaller and lighter, he argues. “People usually laugh when I say this, but calorie intake is continuing to fall and we have probably hit peak obesity as well,” says Goodall. “ So, across the key categories of material use – minerals, metals, biomass and energy – the developed world is seeing an inconsistent but nevertheless clear tendency towards a reduction in use.”

But have we really hit peak curtains? “The idea we’re living in a peak-stuff world is nuts,” says Tim Jackson, professor of sustainable development at the University of Surrey. Some markets may be saturated – Ikea’s soft furnishings, perhaps – but by no means all. Indeed, the ONS statistics should be taken with a pinch of salt. For all that the figures indicate a long-term fall in material consumption, they leave out imports and exports and so neglect the fact that, for example, we are buying more (imported) cars. “The trend is upwards since 2001, if you look at the data sets they leave out,” he says. “The idea that we consume less than a decade ago, as the ONS suggests, is misleading.”

In any case, would being less materialistic make us happier anyway? A few years ago, Daniel Miller wrote a lovely book called The Comfort of Things. It was lovely in part because it confounded the growing orthodoxy that material things ruin or in other ways degrade us. The book was the result of a 17-month investigation into the lives and loves and domestic interiors of 30 households in a randomly chosen London street. In them, the ethnographer found collections of plastic ducks and McDonald’s Happy Meal toys, mementos of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, bottles of whisky from the Queen’s Jubilee, religious images, photographs of reality TV babes, and miniature bottles of foreign liquors.

Why did these things matter, and why did they comfort? Because, Miller thought, they make us what we are, they restore our memories, connect us with others and with the past. “Material culture matters,” he wrote, “because objects create subjects more than the other way round.” The saddest place he visited was a flat of a man called George. “The flat,” Miller reported, “was empty, completely empty, because its occupant had no independent capacity to place something decorative or ornamental within it.” George, sad to relate, had never felt able to take responsibility for anything, not even the decoration of his own home. Rather, his characteristic sense of powerlessness deprived him of the ability to make a home filled with soothing, physical things. Instead, George’s flat contained nothing but the most basic carpet and furniture. It wasn’t, though, a minimalist sanctuary from clutter or a Brooklynite hipster rebuke to overconsumption, but a space devoid of comfort, a heartbreaking expression of self-neglect.

Perhaps the digital counterparts of physical things may offer us consolations, but what is clear is that depriving ourselves of the comfort of things is not a sure fire path to happiness.

END

Be the first to comment