Allowing government officials to have near-total discretion over unmonitored funds creates an atmosphere ripe for undetected abuse. And only legislative reform at the state level will prevent the corrupt misuse of civil asset forfeiture funds.

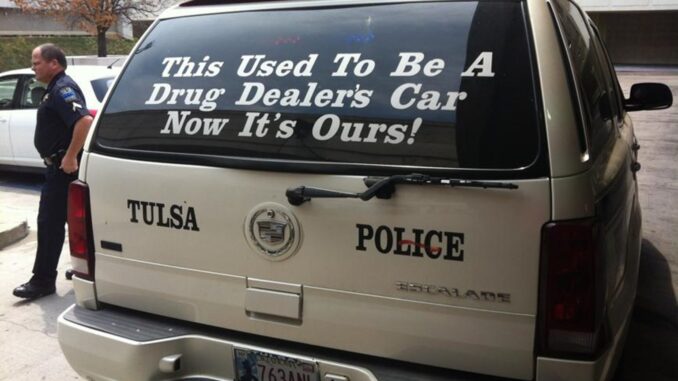

Civil asset forfeiture is a judicial process through which law enforcement officials seize assets belonging to a person suspected of a crime. To be subject to forfeiture, the assets in question must be either the proceeds of crime or were used to further criminal activity, but in many jurisdictions, civil asset forfeiture does not require a criminal conviction, or even the formal filing of criminal charges, and the typical legal threshold is probable cause that the seized property is connected to criminal activity, rather than the “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard generally required for a criminal conviction.

In the international context, civil asset forfeiture is an integral component in the battle against corruption. Empowering law enforcement agencies to seize ill-gotten gains, without the need to first secure a criminal conviction, is one of the most effective methods of punishing corrupt actors and depriving them of the proceeds of their crimes. But civil asset forfeiture is not limited to seizing the proceeds of grand corruption, and in the United States, the civil asset forfeiture system, particularly at the state and local levels, has itself has become a significant vector for corruption, albeit on a much smaller scale, with local officials taking advantage of lax oversight to use seized funds for their own personal benefit. For example, in March, the Michigan State Attorney General’s Office brought charges against Macomb County Prosecutor Eric Smith, alleging that Smith and other county officials had misused forfeiture funds for things like personal home improvements (including a security system for Smith’s house and garden benches for several other employee’s homes), parties at country clubs, and campaign expenditures. Smith is far from the only public official accused of corruption relating to forfeiture funds. To take just a few other examples: State revenue investigators in Georgia used millions in forfeited assets to purchase travel and trinkets-like engraved firearms; police officers in Hunt County, Texas awarded themselves personal bonuses of up to $26,000 from forfeiture accounts; and the district attorney in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania leased a new personal car with forfeiture funds.

To be clear, there are concerns about the civil asset forfeiture system in the United States that run much deeper than the misappropriation of funds. Critics have vigorously attacked both the legal underpinnings of the civil forfeiture system as it currently exists in the U.S., as well the system’s implementation. But for the purposes of this post I want to bracket those larger issues to focus on the question of why the civil forfeiture systems at the state and local levels in the United States pose especially high risks of corrupt misappropriation, and what might be done about this (assuming that the civil forfeiture system is here to stay, at least in the short term).

The United States does not have a single civil forfeiture regime. Within the U.S. federal system, civil asset forfeiture is used by federal, state, and local officials, all of whom operate under separate legal regimes based on their jurisdictions. (Because state and local officials vastly outnumber their federal counterparts, they carry out the bulk of forfeiture seizures — either by themselves or in tandem with the federal government through a process called equitable sharing that allows the state and local agencies to receive up to 80 per cent of the seized profits). In many states, corrupt officials are drawn to civil asset forfeiture funds because the state laws governing the collection and use of these funds are often much looser than those tied to other government expenditures. For example, while Michigan, where Eric Smith allegedly embezzled funds from Macomb County, has a comprehensive regime for the oversight of municipal budgets (and Macomb County itself operates under a rigorous financial transparency framework), the state has no accounting requirements for forfeited assets. And Michigan is not alone. A 2019 study determined half of the states (25 of 50) had no meaningful oversight of seized assets. (Eight of these states had no requirements whatsoever for the tracking of seized assets, while another 17 states had so few requirements that there was essentially no oversight). Additionally, many states that do require accounting of forfeiture expenditures do not enforce that obligation in practice. Furthermore, the majority of states do not mandate any form of financial audits of forfeiture expenditures, while only nine states require either annual or biennial independent audits. As in Michigan, these lax practices regarding the use of assets in forfeiture accounts stand in sharp contrast to general state and municipal budgetary laws, which typically require much greater oversight, including annual audits.

If state legislatures insist on continuing to place forfeited assets in the hands of the law enforcement agencies that seized them, the states should, at least, enact comprehensive oversight procedures to ensure that the funds are properly used.

Allowing government officials to have near-total discretion over unmonitored funds creates an atmosphere ripe for undetected abuse. And only legislative reform at the state level will prevent the corrupt misuse of civil asset forfeiture funds. (Though the federal government provides hundreds of millions of dollars to state law enforcement agencies through equitable sharing, and imposes its own set of oversight requirements for that process, state and local agencies still seize large amounts of assets on their own. In Texas, for example, state and local agencies seized over $50 million in 2017, all of which was separate from their participation in equitable sharing. Any assets seized exclusively through state laws are not subject to federal oversight, leaving state legislatures as the only possible source for future reforms to their own laws). To address this problem, state legislatures should consider the following types of reform:

● Perhaps the best solution would be for state legislatures to remove civil asset forfeiture funds from the control of law enforcement agencies, instead depositing those funds in general accounts for statewide expenditures. This has already been done in some states. Maine, for example, mandates that all forfeiture proceeds must be deposited in the state’s General Fund, which is governed by the state’s robust budgetary regulations. Placing forfeiture funds in general statewide accounts would remove the need to create new oversight regimes specifically for the forfeiture process.

● If state legislatures insist on continuing to place forfeited assets in the hands of the law enforcement agencies that seized them, the states should, at least, enact comprehensive oversight procedures to ensure that the funds are properly used. To start, law enforcement agencies should create publicly accessible databases that list every seized asset and track the disposition of each case. After assets have been officially seized and converted into funds for government use, they should be deposited into specially noted accounts, rather than directly into the law enforcement agency’s general budget. All withdrawals from that special account should be documented in detail, so that auditors can connect every spent dollar to a specific, legitimate government purpose. These reports should be compiled annually and sent to a central oversight body.

● Agencies that do not comply with these requirements should be subject to fines or possibly a bar on further spending of forfeiture funds. Finally, states should require regular financial audits of all aspects of the forfeiture process for any state or local agency. Some states have already adopted reforms along these lines. Arizona, for example, has enacted the most stringent oversight regime and should be a model for other states.

● Serious reforms will inevitably create pushback, especially from agencies used to spending forfeiture funds largely unchecked. But criticism of asset forfeiture has been steadily building for years, and 35 states, as well as the District of Columbia, have reformed their civil forfeiture laws since 2014. Thus, there is political appetite for overhauling civil asset forfeiture laws. Without such changes, corrupt state and local officials will continue misusing forfeiture funds for their own benefit.

Richard E. Messick is a Washington D.C.-based international consultant.

END

Be the first to comment