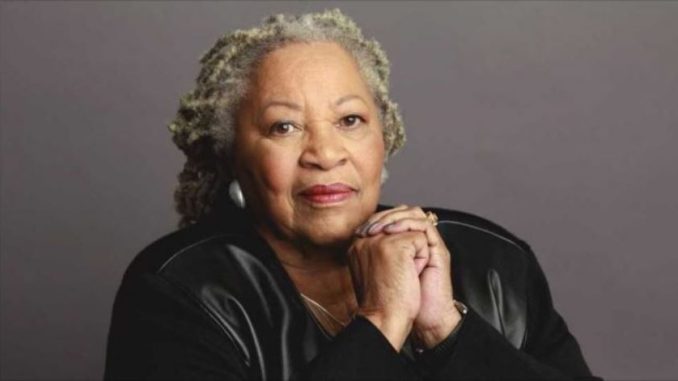

Toni Morrison, the African-American Nobel prize laureate, who died on 5 August at the age of 88, was a true force of nature. Born in the steel-mining town of Lorain in Ohio on 18 February 1931, she grew up in a cosmopolitan environment with the descendants of Poles, Italians, and Spaniards. But, this was also the time of the Great Depression, and the family struggled financially. Morrison’s grandfather had been a slave. Her father, George Wofford, worked several jobs in order to pay the rent, while her mother, Ramah Willis, was a housewife and home-maker, looking after four children. Morrison experienced some harrowing experiences from a nomadic childhood moving from house to house. An arsonist landlord once tried to burn down their home in order to evict the family. But her Midwestern childhood was also full of African-American music, myths, folktales, and fantasy, planting the seeds for much of her later creative work.

Morrison – who converted to Catholicism at the age of 12 – attended the most prominent historically-black college, Howard University, in Washington D.C. studying English, but also taking an active part in Drama and acting in plays about African-American life. She dived deeper into the Western canon that she had been exposed to in high school: Leo Tolstoy, Gustave Flaubert, and Jane Austen. She joined a sorority, which she later discovered was for light-skinned black women, thus becoming exposed to the politics of pigmentation. She also experienced the segregation of public services like transport and toilets in the capital of apartheid America.

Morrison left the ebony tower of Howard in 1953 for the Ivy League of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York; to do her Master’s in English. She returned to teach at Howard, with Trinidadian-American activist, Stokely Carmichael, being one of her students. In 1958, she married Jamaican architect and academic, Howard Morrison, whom she met at Howard. The unhappy marriage produced two sons – Slade and Harold – but ended after six years while Morrison was pregnant with her second child. She would later controversially complain that the union failed partly because “women in Jamaica are very subservient in their marriages. “

Morrison then found a job as an editor in Alfred Knopf – later Random House – based on an advertisement she had seen in the New York Review of Books, eventually becoming its first black female fiction editor. Desperately lonely, she woke up every morning at 4 a.m. to write, while raising her two young sons. She used her job as editor in a lily-white industry to empower black writers and expose them to the American mainstream, publishing books by Angela Davis, Muhammad Ali, Gayl Jones, June Jordan, and Toni Cade Bambara. She consciously set out to create a “canon of black work” in an unselfish and self-effacing mission. Her Pan-Africanism was reflected not just in her marriage to a Caribbean man, but in her production of anthologies of Nigeria’s two most renowned writers: fellow Nobel laureate, Wole Soyinka, and Chinua Achebe.

It took Morrison five years to complete her debut novel The Bluest Eye (1970), about an 11-year old black girl so consumed by self-hate that she prayed for blue eyes. The girl was later raped and impregnated by her father, sending her spiraling into insanity. Despite this ghastly outcome, the book was also an ode to the “Black is Beautiful” and “Black Power” slogans of the era. Morrison had published Bluest Eye without letting her employers know. When they found out, they brought her into their stable, and would publish all of her subsequent books. Morrison resigned from Random House in 1983 to write full-time.

She insisted on focusing on strong black characters – usually women – telling their individual stories within the larger context of a racist America, insisting that she would narrate these tales on her own terms, “without the white gaze.” As Morrison memorably noted: “I’m writing for black people, in the same way Tolstoy was not writing for me.” She insisted on writing about the little people that the more conventional “Big Man” version of history had forgotten. She also wrote about the redemptive spirit of black communities and the triumph of the human spirit in the face of overwhelming adversity. She dealt with unflinching honesty with difficult issues of murder, rape incest, and racism. She believed that the past was not yet past, and still remained behind to haunt the present. The “magical realism” in some of her books led to comparisons with fellow Colombian Nobel laureate, Gabriel Garcia Marquez.

Morrison’s second novel Sula (1973) dealt with the tale of two black women in a Midwestern American town and their relationship of sisterhood. The lyrical Song of Solomon (1977) brought Morrison to national attention, dealing with a middle-class Michigan man in search of his personal and family identity. Tar Baby (1981) was set on a Caribbean island; Jazz (1992) evoked the Harlem Renaissance of the 1920s; Paradise (1997) was located in an all-black community in the Western US; Love (2003) dealt with the aftermath of the death of a black hotelier; A Mercy (2008) returned to the theme of early American slavery; Home (2012) focused on the relationship between a black returning Korean war veteran and his sister; God Help The Child (2015) returns to the theme of a black woman confronting racial prejudice.

Beloved (1987) was, however, Morrison’s magnum opus. This story of infanticide was based on a true incident of an escaped 19th century slave woman who slit her child’s throat when recaptured, so that she would not have to live in slavery. The ghost of the child would later return. Oprah Winfrey, Danny Glover, and Thandi Newton starred in the 1998 film version, which flopped at the box office.

Despite Morrison’s talents, she had to wait two decades to be given the acclaim that she deserved in a sector that remained stubbornly white and male-dominated. Song of Solomon had won the lesser National Book Critics Circle Award in 1977. Morrison’s books appeared regularly in the New York Times bestseller lists, as well as the influential Oprah Winfrey book club. When Beloved failed to win the National Book Award in 1987, 48 black writers – including Angela Davis, Maya Angelou, and Alice Walker – placed an open letter in the New York Times complaining about this lack of recognition. The book won the Pulitzer Prize a year later. The Nobel Prize followed in 1993 – the first black woman ever to win it, and the first native-born American in 31 years – cementing Morrison’s global reputation and winning her millions of new readers. Morrison also taught at the elite Princeton and Yale universities, becoming the first black woman to hold a professorial chair at an Ivy League university (Princeton) in 1989 even without a doctorate. Barack Obama awarded her the presidential Medal of Freedom in 2012.

But, despite her role as an outspoken public intellectual consistently condemning police brutality against minorities, Morrison could sometimes be politically naïve. She described Bill Clinton in 1998 as America’s “first black president” without examining in detail the devastating impact of his crime and welfare policies, as well as his spectacular failures during the 1994 Rwandan genocide. She seemed infatuated with her friend, Barack Obama, without critically analysing his failure to demonstrate the courage of his conviction in prosecuting deadly drone warfare and securitizing US policies in Africa. She backed Hilary Clinton without critically assessing her support for harsh crime measures and a harmful, hawkish foreign policy in Libya.

Morrison wrote 11 novels, two plays, three collections of essays, two books of short fiction, and five children’s books. The death of her 45-year old son Slade (who co-wrote some of her children’s books) in 2010 – from pancreatic cancer – was a devastating blow, from which she never really recovered.

Barack Obama described Morrison as “one of our country’s most distinguished storytellers”; Alice Walker called her “a great writer whose extraordinary novels leave an indelible imprint on the consciousness of all who read them; “Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie noted that “she was Black and she didn’t apologize for her Blackness;” Arifa Akbar observed that Morrison delivered “unwavering truths with an intelligent rage that is almost equal to hope;” Ben Okri praised the “unique jazz-tinged poetry of her tone;” while Aminatta Forna described Morrison as “one of the greatest of a generation of writers who helped to shift the centre of the literary imagination.”

Despite signing a contract for a memoir, Morrison never wrote it. A 2019 documentary “Toni Morrison: The Pieces I Am” directed by her Grammy-winning friend, Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, however, captured the key moments in her life and work, as the indomitable silver dread-locked Black Bard and contemporary griot – who insisted on being referred to as a black female writer – talked directly into the camera. It is a worthy tribute to a remarkable and uncompromising woman of letters of the African Diaspora. The most eloquent chronicler of American slavery has ironically died in the year of the 400th anniversary of this grotesque crime against humanity.

Professor Adebajo is Director, University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation, South Africa.

Be the first to comment