Forced migration and its concomitant enslavement of the African was a blight on the world’s collective conscience between the 1500s and 1800s. The repercussions still reverberate through time to the present. Africans are calling for payment of reparations to their motherland by the European powers till date.

It is paradoxical that the ships of the slave masters were filled with unwilling and forced migrants, brutally repressed and tortured to keep them on board, yet some would rather drown than move away from their motherland and the place they considered as home.

A friend once told me that if US or UK berths a ship on the shores of Nigeria today and asks young people if they want to leave and migrate to either of the two countries on the said ship, the number of people who will voluntarily get on board will sink the ship. The struggles, fights, and shovelling that will be seen would make “Wrestlemania” look like child’s play. As sad as this assumption is, statistics back its fundamental realities.

A recent PEW research survey reveals that about 45% of Nigeria’s adult population plans to relocate to another country within five years. Of the 12 countries surveyed from Africa, the Middle East, Europe and North America, Nigerians ranked highest among people who desperately want to relocate to some other countries. In another study in 2021, it was revealed that seven in every 10 Nigerians planned to relocate if the opportunity presents itself.

A new report by the UK government shows that the 13,609 Nigerian healthcare workers granted working visas within the last one year (2021) are second only to the 42,966 from India. According to the UK immigration report released last Thursday, Nigeria is second only to Indians in the number of visas granted to the ‘Skilled Worker – Health & Care’ category, with 14% (13,609) of the total. Recent official data from Canadian immigration sources indicate that 12,595 Nigerians relocated to Canada alone in 2019 alone. There were 4,000 applications for permanent residency by Nigerians in Canada in 2015. By 2019, the number had climbed to 15,595 – an increase of over 214.9%.

The recent wave of Nigerians relocating out of the country represents the largest movement of people out of the country since the end of the civil war, over fifty years ago. What is significant is the profile of those who are relocating. They are primarily skilled youth, including doctors, nurses, IT engineers, university lecturers and technicians. They also include young people who completed their studies abroad and opted to stay back because our country has nothing to offer them with regard to jobs, opportunities, or even basic safety. Some of them have been educated in elite universities at home and abroad. This demographic is more debilitating for our national developmental prospects.

The primary strategic concern of our increasing demographic haemorrhage is the emigration of skilled Nigerian youth. The people on whom our future depends are leaving. Our best energies and brains are being drained. Our IT wiz kids, medical scientists, economists, biotechnologists, and academics , etc. are flooding flights headed out to better climes. Many of them have no plans of returning home in any hurry. A certain disturbing pessimism that this place will not get better any time soon pervades the attitude of many of these fleeing youth. They are leaving because the place we call home has degenerated into a hell hole of calamities, devoid of opportunities or hope.

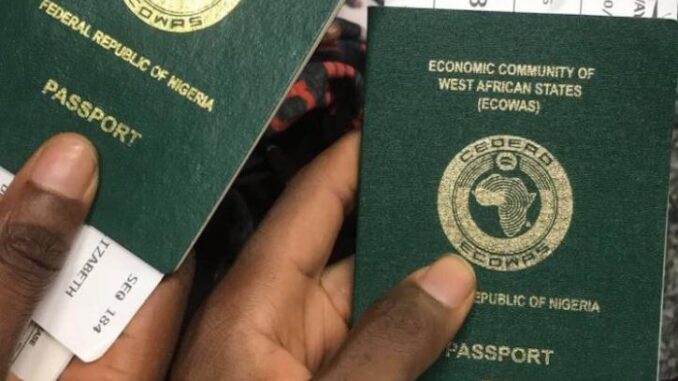

The Nigerian government appears unperturbed by the outbound migration of its professionals and young people. The number of passports issued by the Nigeria Immigration Service rose by 38% between 2020 and 2021. This increased from 767,164 to 1,059,607 passports granted in 2020 and 2021, respectively. This is an indication that more people are planning to move out of the country. The government, in terms of policies and actions, is not putting anything on the ground to stem this tide.

Five major factors seem to be fuelling this voluntary migration from Nigeria, which has never been seen since World War II. These factors include the desire for better career opportunities, heightened insecurity in the country, the need to provide a better future for one’s children, the requirement of further education, and poor governance in the country. To underscore these points, a cursory look at Nigeria’s economic statistics paints an ugly picture.

First, there are limited employment opportunities, as the country’s unemployment rate rose five-fold (from 6.4% to 33.3%) between 2010 and 2020. Unemployment creates or increases the chances of poverty, and a rise in unemployment, as revealed by Nigeria’s data, means more people are being pushed under the poverty line. In recent months, unemployment and poverty primarily affect the youth, and crippling inflation has exacerbated the problem. Inflation has moved from about 7% a decade ago to over 20.52% lately (August 2022), forcing more people into poverty.

The security challenge is worsening by the day, with constant escalation of societal tensions by the activities of kidnappers, bandits, secessionists, terrorists, and other forms of criminality. The insecurity level has become a significant concern, with the death toll in nine months reaching 8,281, and 3,490 persons kidnapped in only eight months in 2021. ASUU has been on strike for almost nine months now, with no clear sense of direction. Therefore university students remain at home. The only option to these peculiar Nigerian problems is to “japa” (a Yoruba slang for escape).

If Nigeria’s socio-political and economic climates remain averse and strangulating, young people, even middle-career parents, will abandon the country and relocate at the slightest opportunity. This trend is not likely to end soon. Tragically, the areas worst hit by the current wave of migrations are the most strategic for our nation. We may quickly lose our competitive and comparative advantages in IT, Engineering, Medicine, and other highly skilled jobs due to those emigrating in droves. In years to come, the opportunity cost of this migration may be too high to contemplate.

The irony in some cases is that most of these people travelling received their training and education in public institutions funded by the Nigerian government, and the developed countries will simply reap the rewards that ought to accrue to Nigeria (a reversed aid from Nigeria to developed countries). Those from families that can afford to cover the costs of studying (while expending huge sums in foreign exchange) or working abroad have no plans of ever returning to Nigeria soon. The pull of skilled migration is quite high. With aging populations in most developed countries, a dearth of professionals and highly skilled workers in STEM (science, technology, engineering and maths) areas, and the advantages of a diverse workforce, the developing countries are in demand of professionals with the suitable skills base and English language proficiency.

The Nigerian government appears unperturbed by the outbound migration of its professionals and young people. The number of passports issued by the Nigeria Immigration Service rose by 38% between 2020 and 2021. This increased from 767,164 to 1,059,607 passports granted in 2020 and 2021, respectively. This is an indication that more people are planning to move out of the country. The government, in terms of policies and actions, is not putting anything on the ground to stem this tide. It rather seems that the government has an alternative view of this mass migration.

The long term solution to the japa syndrome is multi-pronged. It requires a fundamental renewal of the educational system at the tertiary level. It needs a shift of emphasis from certificate education to entrepreneurship education. We need at least eight years of the uninterrupted inflow of foreign direct investment to create an average of three million to five million jobs per annum.

The government seems to be toeing the view that as a large country with a population of over 200 million people, it is a good thing to export its skilled labour. About 50,000 people leaving a country of 200 million people annually should not be a red flag, as those left behind are more than the few who will make it out. However, it is this migrating group that ought to bother the government more.

Some argue that the next generation’s exodus will help increase diaspora remittances, which lately has been the booster to the national dollar reserve. Diaspora remittances reported by the CBN currently hover between $25 billion and $30 billion annually, and is still rising. The country can earn close to $100 billion annually if it harnesses the remitting potentials of its various diasporas. The Labour Minister, Chris Ngige, affirmed this view when he told journalists last year that the country was exporting its best minds because it had a surplus of talents and, in any case, “when they go abroad, they earn money and send it back home here.”

Some Nigerians do not see anything wrong with this mass movement of skilled professionals, in peace time, abroad. They argue that it’s the same way a generation of Nigerians once left the villages in droves for cities and urban centres across the country. Education, lack of employment opportunities and shrinking socio-economic conditions will ensure forced migration anyway.

India, a country facing a similar situation, has created a robust policy and institutional framework to reverse this trend which portends danger for the country’s future socio-economic development. Among the steps taken include but are not limited to creating employment, attracting international companies to site industries in India, and creating awareness of the inevitable growth of the country as a global economic powerhouse soon. The hope of a better Nigeria is a recipe for keeping young professionals from migrating, and this underscores the importance of the 2023 general election. The new breed of leaders that will emerge must inspire hope in the future of Nigeria.

The long term solution to the japa syndrome is multi-pronged. It requires a fundamental renewal of the educational system at the tertiary level. It needs a shift of emphasis from certificate education to entrepreneurship education. We need at least eight years of the uninterrupted inflow of foreign direct investment to create an average of three million to five million jobs per annum. Above all, it requires an onslaught on insecurity to enable internal migration of the factors of production, especially labour and capital, from one section of the country to the others. Deliberate steps must be taken to improve the quality of social services in the short and medium term.

Taken together, these measures will help reverse long term mass migration from the country by creating a conducive environment for citizens to pursue and realise their potentials within Nigeria. They will also enable a gradual year-on-year reversal through the rights of return and homeward movements.

Dakuku Peterside is a policy and leadership expert.

END

Be the first to comment