Introducing A People Defined by Hierarchies

Nigeria is a country defined by hierarchies in which everyone is expected to fit neatly into a box. These hierarchies are many and multi-dimensional. They vary in both shape and size and we have signature tunes for sign-posting them. You know a generational put-down when it’s uttered. When you hear, “Am I your mate?” or “your time will come”, it doesn’t matter if you are already a sixty-something year-old grand-parent. “Where are you from?” is a marker for geographical hierarchy that easily also conflates multiple sign-posts of ethnicity, religion, race and even presumed political persuasion. “You no know say you be woman?!” assumes lessons in propriety are exclusive to one gender. It is Nigerian to accept these hierarchies and their implications without question. To not subscribe to this is to subvert something widely considered essential to the Nigerian identity. It’s an invitation to trouble.

Our Nigerian hierarchies and accompanying boxes of identity even find expression in our sartorial preferences. They’re also canaries for prejudice and for competing claims of exception. Those who don’t fit into these boxes are worse than mere outliers. They could also end up as outcasts. Civic ecumenism in Nigeria is thus at once endangered but fascinating. It’s both vice and virtue. In this, art imitates form. A Nigerian who appears to embody these virtues could end up being both endangered and, simultaneously, a subject of considerable fascination. Notoriety is their reward. The best-known exemplar of this is Fela — he was so notorious, he did not need the luxury of a surname; so admired, everyone believed they knew him on intimate, first name terms.

Neither Faint of Heart nor “Agbero” Bourgeoisie

This is not a fate for the faint of heart. After all, we are Nigerians, the largest community in Africa. Just about any fraction of us against one person would be an army. Even in a world now dominated by fatuous obsession with seconds of infamy, no one dares to embrace an army’s worth of ire just for the sake of cheap popularity or fame. It takes conviction and courage to go against Nigerian hierarchies and all that they entail.

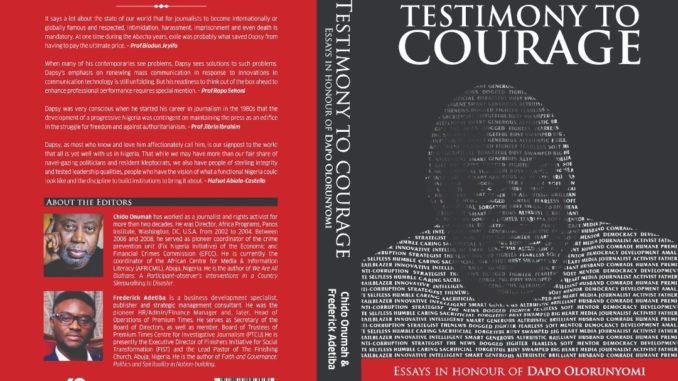

This is the point of Testimony To Courage. It is a collection of “Essays in Honour of Dapo Olorunyomi”, another Nigerian who, like Fela, is descended from a lineage of Christian missionaries and, also like Fela, is now best known by an edited form of his first name as “Dapsy”. Those of us too animated by Nigerian hierarchies to feel so intimate with our Egbon would take liberty to preface “Dapsy” with “Oga”. You know this cognomen has passed the test of acceptance when it receives the reluctant approval of the ideologically fastidious Biodun Jeyifo, emeritus professor and Dapsy’s teacher, who would have voted it down because “it sounds like and rhymes with ‘Popsy’ and ‘Momsy’, two of the most overused terms of the special argot or vocab of the over-pampered offspring of our national bourgeoisie.” But he is prepared to grant an exception to its use for one of his favourite students because “there is nothing in (Dapsy’s) character and his sensibility that smacks of the moral and social universe of our agbero bourgeoisie.”

A Conclave of Witnesses To Civic Ecumenism

The book is at once about a man, his life’s passions, and about courage as a civic virtue. Courage, on its own could be both virtue and vice. As an end in itself, it is meaningless. It only makes sense as a means and its elevation to a virtue assumes the existence of a larger goal into whose service it is pressed with consistency. Three of Dapsy’s abiding passions — Nigeria, other people and truth — receive substantial attention in the book. It’s easy to stray into one, some or all of these and forget about the book. Yet, a review of the book would be bereft without these.

Testimony To Courage hews close to the man in its ecumenism and disregard of Nigerian hierarchies. It contains 91 essays, 90 of which are relatively short. The exception, predictably, by essayist, Odia Ofeimun, occupies all of 34 pages. The essays are clustered into three different parts that supposedly capture the essence of Dapsy’s life, work and values. Part 1, containing 33 essays, is devoted to his “Journalistic Exploits”. Part two contains 26 essays and deals with his “Activism and Democratic Struggle”. The 32 essays in part three are devoted to his “Legacy” of “Investing in the Future”. The categories are far from neat. Three additional essays are published as prologue, preface and introduction. They are all worth reading and highly readable.

The contributors include senior citizens above 80 and young people in their 20s; senior politicians on one hand and citizens, some of whom hold them in barely concealed contempt, on the other; pastors and atheists; Christians, Muslims and traditional worshippers; men, women and every gender in between. At one end of the generational spectrum of authors are people like Akin Olorunyomi, Dapsy’s elder brother, who was there when he was born and named in 1957; Wole Soyinka, after whom Dapsy has built one of the institutions that has become his hallmark; and Ropo Sekoni, an emeritus professor, who was Dapsy’s lecturer in the university over 40 years ago. At another end you have contributors like Omotola Aderinsola, who confesses to having known Dapsy for “less than a year”, and Farooq Kperogi, who has never met Dapsy in person. With a few exceptions, the editors manage to distil from this conclave of witnesses a rich and highly readable variety of insights about man, virtue and country. The rulers of Nigeria have quite a lot to learn from the civic ecumenism of the book and of its subject for, true to Dapsy’s inclinations, it cannot be said of this book that any part of Nigeria is marginalised in it!

Constancy and Coincidence; Dissonance and Diversity

This rich variety makes it somewhat difficult to be too categorical about the book. Testimony To Courage is broadly characterised by transcendental themes, some in dialogue with others. These are themes of constancy and coincidence; dissonance, diversity, and even the divine. It also offers a deep trove of information on Dapsy from the biographical to the aesthetic, which provide both context and interpretation for the deep strain of conviction and courage that he is known for.

Let’s begin with the biographical. We learn from the book that Dapsy was born in Kano to parents who lived in Keffi, but whose origins were in Okun-land. His grandfather was an ordained Baptist Minister and his parents were of the missionary persuasion. There is evidence of a deep pedigree that is emblematized in his birth names: Oyedapo (royalty has merged); Oyekunle (home filled with royalty); Adeniran (crown belongs to family). For a man who belongs to that rare species born adult, the irony is telling that this book formally gets launched on 27 May, usually marked in Nigeria as “Children’s Day”. His brother, Sola Olorunyomi, narrates, for instance, that Dapsy was wont to defy wearing a bib around the dining table at home with the refrain “do I look like a kid!?” For his sins, his younger sister, Adenike Odebiri narrates, his mother shipped him off to boarding school at four so as to “give her peace in the house.” He ended up going to a Koranic school in what is today Zamfara State and attending six different primary schools in six years. By the time he was finished with secondary school, Dapsy had lived in Bauchi, Gusau, Ilorin, Keffi, Makurdi, Mubi, Zaria, becoming proficient along the way in English, Fulfulde, Hausa, Yoruba as well as in the Bible and the Qur’an. He would later go to Ife for his undergraduate studies and then Yola for his compulsory national service. It’s no coincidence that his other endearments are “Mallam” or “Almajiri”.

The theme of coincidence and trouble is constant in Testimony to Courage. Dapsy’s mother did not have a monopoly of inventive ways to manage his penchant for trouble. Senior Advocate of Nigerian (SAN), Femi Falana, narrates that at the University of Ife, where they were editorial collaborators in a campus magazine, The Voice, the authorities banned the journal. In Dapsy’s professional biography, the rendezvous with reportorial immolation appears with unceasing regularity. As editor of another campus newspaper, The Rapport, he reportedly published a factually accurate story of how “a senior lecturer marched a female student into the hall to conduct a special examination for her”, outside the examination schedule. Unable to fault the story nor contain the furore caused by it, the university authorities had the magazine banned. As a reporter with African Concord, he wrote a story about the cynical sclerosis of the Ibrahim Babangida regime in April 1992 that got the regime angry. When they could not get the magazine to withdraw the story, the regime had the Concord group shuttered. That led to the founding of The News and Tempo stable under Gen. Sani Abacha but, “before long, both magazines were proscribed by the discredited dictator.” They set about looking for him and when they could not find him, they even closed down his family life by arresting his wife, Ladi, and child!

Dapsy would later join forces with Dele Olojede at Next, which became so successful in investigative and enterprise journalism it had to be “rested”. Vanguard Editor, Eze Anaba, mourns Next as “a brilliant initiative that came too early.” His latest enterprise, Premium Times, has not been without its own share of troubles but the digital revolution now provides some inoculation against similar pretensions to martial decapitation of journalistic irritation. The point of Testimony to Courage, however, is the constancy of Dapsy’s commitment to truth even in the face of a rampant cemetery of publishing titles that testifies to the official conspiracy against it.

There is an easy point of consensus in Testimony To Courage. As co-editors, Chido Onumah and Frederick Adetiba sum up in the introduction, “one thread run across everyone’s experience of Dapo Olorunyomi — his extraordinary humanity.” This “extraordinary humanity” often expresses itself in unusual generosity that “shows total disregard for personal comfort, privilege or position”. The word “bohemian” appears in more than a few places in the book, evidence of an attribute about which, Idowu Obasa complains, “makes people who are modestly conscious of these things appear very vain and self-centered.”

Far from a bookend, this kind of dispute over the nature and limits of virtue is a major theme of the dissonance that is evident in Testimony to Courage. There is an illuminating dialogue in the book between medium, message, values and means. The various authors, for instance, can’t seem to agree even on what Dapsy does and where he has made his mark. Odia Ofeimun believes that the book is by “media activists” about a man who has been at the cutting edge of “investigative journalism”. Yet most of the articles arguably centre not on his journalism but on his activism, humanism and institution building. Later in the book, Ofeimun would admit to many more dimensions to Dapsy’s narrative, acknowledging him also as a leading student activist and a “civil society stalwart.” In his own words, Dapsy is quoted as describing himself as being engaged in “content production enterprise”, from which vintage he sees publication merely “as a platform.” All this is not unconnected, of course, with the disruptive impact of the digital revolution on journalism, free expression and activism producing much more information without necessarily improving enlightenment. The resulting “assembly line” journalistic value-chain makes it impossible to shut down publishing today as the military did before.

With so much dissonance on such fundamentals, Testimony to Courage is naturally in diversity of viewpoints and insights on matters big and small. For instance, two contributors to the book include recent Osun State Governor, Rauf Aregbesola and former Lagos State Governor, Bola Ahmed Tinubu, whose self-image is as agents of good. Yet two of the contributions describes their class as part of “the rampant power they had criticized in the past” and as now representing the “compromised bowels of the decadent institutional structures that were the object of the strictures” of Dapsy’s work.

This diversity is replicated on even minutiae. Nobel Laureate, Wole Soyinka (Kongi), describes Dapsy as “mild-looking”. For those inclined to think of the subject on this account as mild and retreating, Elor Nkereuwen counters that she found him “loud and boisterous”, an attribute, she makes clear, she doesn’t like. Omotola Aderinsola even found him “slightly pot-bellied”. From their keypads, however, what would otherwise appear negative manage to come out almost as endearments. Confirming this, they both confess to how they are separately drawn to him as a peerless mentor. The dialogue between Kongi, Omotola Aderinsola and Elor Nkereuwen is also a record of an inter-generational conversation mediated by Nigeria’s hierarchies. Is it possible that the man who is required to be mild-mannered before his elders can also be boisterous before his Aburos? What this says about what matters to the different generations is one of the subliminal under-currents of Testimony to Courage. It falls to Waziri Adio, caught as he is between the generational hierarchies, to reconcile the appearances of contradiction in a man who is “at once understated and forceful, playful and serious, unassuming and cerebral, carefree and caring; approachable and cerebrally intimidating.”

Testimony to Courage is more than just a collection of feel-good testimonials. It is a very serious and multi-disciplinary contribution to contemporary political economy, history, civic activism, security and media studies, with some spell-binding vignettes. Dare Babarinsa tells of the arrogant perfunctoriness with which Ibrahim Babangida made himself “President” instead of military “Head of State”, as his predecessors were known.

In another section, we learn that pioneer chairman of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC), Nuhu Ribadu, whom Dapsy would serve as Chief of Staff, was, in an earlier life during the reign of General Abacha, his tormentor, as a minion of Zakari Biu, the powerful ex-Police Commissioner who was one of Abacha’s security Commissars. In that capacity, Ribadu was one of the security men who kept tabs on Dapsy. He confesses that to this day, he still has “Dapo’s passport recovered from those days.” It must now be a collector’s item.

In one of fate’s bitchier twists, Ribadu himself, from Adamawa, in north-east Nigeria, was forced into exile after his EFCC tenure, on which journey Dapsy became his Ebenezer. To smuggle him across Nigeria’s land borders for that escape, he had to be dressed up in “a fitting Yoruba dress… with a matching Buba.” It remained for him to find an equally fitting Yoruba name. So, they gave him the name “Bayo”. His otherwise uneventful march into exile was punctuated at the border with Benin Republic where the Gendarmes thundered: “Arretez! Ou allez vous?” To which his minder, no doubt prompted by the spirit (to use a Nigerianism), responded without missing a beat: “Porto-Novo. Mon ami va rencontrer sa fiancée! stern questions from armed Gendarmes, who knew the height men could go to have a rendezvous with a lover across the border.”

That lover, of course, is freedom, a lover the contours of whose intimacies and assignations with Dapsy are chronicled in every page of Testimony to Courage. The pieces are crafted with wit, humour, profound depth of recall, clarity mostly and, surely for a Nigerian book, occasional bombast. For example, Omoniyi Ibietan indulges in a spot of “totalizing the phenomenology of my encounter with Dapsy, his intentionality…”, a line that would feel entirely natural in Ene Henshaw’s This is Our Chance or, indeed, in Uanhenga Xitu’s, The World of Mestre Tamoda. A relatively brief index should ordinarily help readers navigate the book although it could easily have been more helpful if it had been more extensive. Navigation would have been helped, also, by indicating the names of contributors against their entries in the table of contents. Without that, locating particular authors or sections in the book can be cumbersome. If only to correct this, among other goals, this book deserves a second edition. When it happens, that edition could also offer an opportunity to such important and close collaborators of Dapsy’s as Bayo Onanuga, Babafemi Ojudu, Seye Kehinde and even Ifeanyi Uddin, to meet editorial and production deadlines.

The Courage to Re-Make Our World

Unsurprisingly for a book whose principal protagonist is a descendant of Christian missionaries who has survived arrest, detention, torture, exile, and critical illness, to inch beyond the earthly landmark of three scores, Testimony to Courage genuflects before the divine with elements of a thanksgiving. One contributor who confesses to not knowing whether Dapsy is “a Christian or a Muslim or both” nevertheless pronounces him “an embodiment of God Almighty.” Reflecting Dapsy’s inclination to take the long view, it falls to Idowu Obasa to put the remarkable narrative encapsulated in between the covers of the book into perspective. Obasa recalls that Dapsy’s many run-ins with power “led to what appeared to be permanent exile in the USA” but admits that he “cannot fail to thank God for the fact that if he had not run away to the USA those many years ago, we may have lost him two years ago.”

Herein lies the strongest message of the book—the man of courage who lives to tell the tale is usually the one who takes a long view. The courage to which this book testifies is of a more fundamental variety than that of a media practitioner or of an investigative journalist. It is about the courage to seek to re-make society away from the hierarchies that make demi-gods of a few, tarnish the other with toxic prejudice and diminish opportunities for everyone. It is a courage born of educated curiosity and underpinned by the inexactness of an experimentalist. It is courage of the wayfarer’s variety defined by a journey on which the destination may be known but the route unclear. It is this uncommon courage that Dapsy continues in different forms to embody.

In a country where “those who are least deserving get the loudest accolades” while “some who are deserving get their recognition after their death”, Testimony To Courage is evidence that the supplication for civic canonization does not always have to await earthly mortality. Sometimes, a generation must acknowledge its best in order to encourage many more not to give up on virtue. At the personal level, I suspect it may offend against Dapsy’s natural modesty to be held up to such high admiration or become the object of such elevated fascination. He may yet be persuaded to accept with some reluctance, however, that it’s a price worth paying for the cause of recruiting more people to his inestimable passion for humanity and for a country that works for all who care to call it their own.

Chidi Anselm Odinkalu is senior team manager, Africa, Open Society Justice Initiative.

Title: Testimony to Courage: Essays in Honour of Dapo Olorunyomi

Editors: Chido Onumah and Frederick Adetiba

Publishers: Cappa & Omega Co., 2251 Tangayika St., Maitama, Abuja

Page Numbers: 404

Price: Unstated

Year Published: 2019

Be the first to comment