It is no longer news that the Nigerian educational system, due to an unwholesome combination of neglect and mismanagement, has fallen over the years into a squalid state of disrepair. It is no longer news that while in saner societies throughout the world, the teaching profession is considered one of the most important jobs there could be, in Nigeria, teachers are about the most indigent, most derided lot in the polity.

It is also not a so surprising truth anymore that if the achievement of peace, stability and development is one of the objectives of the Nigerian state at this present time, its school curriculums are ill-equipped to drive the nation towards that goal.

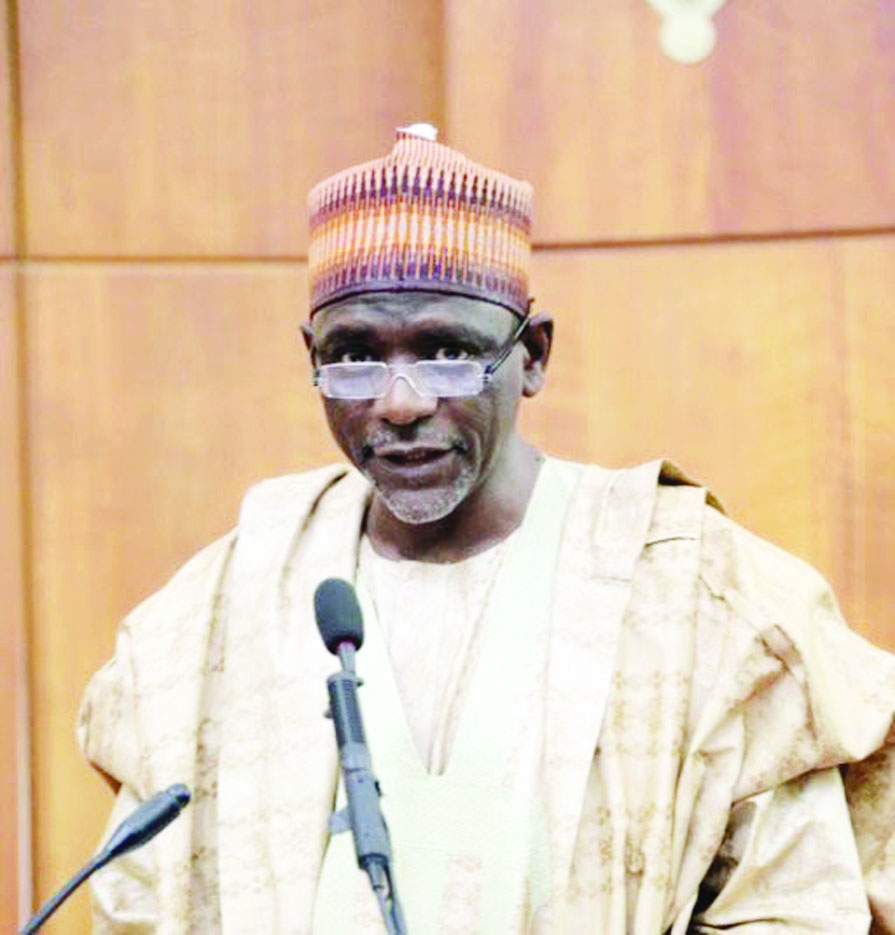

Minister of Education, Adamu Adamu, was therefore saying nothing new when he complained about the shortage of teachers and called for an urgent review of the curriculum at the seventh conference of the Africa Federation of Teaching Regulatory Authorities (AFTRA) in Abuja the other day. More important than a reiteration of what many other stakeholders have since been clamouring for, and infinitely more fruitful, would have been an active pursuit of policies that will give the educational system the improvement it so much needs. But, in Nigeria, those who are supposed to be the doers happen to be the most petulant complainers.

The derision of teachers and the teaching profession deserves more than a passing mention. The decline in the value of teachers, obvious as it is, would be all the more troubling to the discerning mind, being symptomatic of a more insidious erosion of the greater, more abstract values that should normally hold the fabric of a nation together. Teachers represent, among other things, the value of learning, of the transmission of important values, traditions, knowledge, skills, and secrets for surviving and thriving from an older generation to a newer one.

If, to paraphrase Hannah Arendt, education is an indispensable means by which children are properly introduced to a complex, multifarious world, the teaching profession is the formalised vehicle by which this introduction is done in a standardised, measurable fashion. Within the context of a civil, organised society, therefore, teachers represent the hope for the continuity of a nation, tasked with making sure that the younger generation is able to cope with the world it will inherit.

Where teachers are not taken care of and properly trained, then, the direct implication is that the very continuity of that social space is threatened. In Nigeria, disdain for the teaching profession has almost become a norm. Teaching is now what people do in order to not just sit at home. Teachers have to make do with poor remuneration, poor welfare, and poor self-esteem, so much so that even in popular songs, the fate of the teacher is revealed as being an ineligible bachelor, not deserving to marry from the best of families. Worse of all, teachers themselves seem to have accepted, indeed embraced, this scornful treatment. “I am a teacher” has become a most potent incantation for the shirking of (financial) responsibilities.

This situation calls for urgent action, because the threat of discontinuation is even more terrifying for Nigeria. The misplacement of priorities, the veneration of mediocrity, has pushed the country to the edge of a precipice. Something must now be done or, in the future, pundits will be trying to understand how Nigeria became, to use the words of Wole Soyinka, “at best, yet another failed state, (and) at worst, an overcrowded necropolis where the hope of the future lies interred in unmarked graves.”

Solving the problems in education might be a challenge, but it is not an impossible one at all. Indeed, it requires more of discipline and due diligence than it requires genius. For a nation that is serious about its own sustenance and improvement, and having realised that these are ultimately tied to the quality of education and the wellbeing of teachers, improving the lot of the teachers (in terms of training, remuneration, and general welfare), should be a priority.

It is also very important to strictly professionalise teaching, rather than maintain the status quo of having a preponderance of ad-hoc, untrained, and uncertified teachers. The instruments for the professionalisation of teaching already exist and merely need to be properly strengthened. There is, for example, the National Teachers Institute and the Teachers Registration Council of Nigeria, constitutionally empowered to train and approve teachers. These institutions have been neglected in the scheme of things and now need to be re-empowered to take the lead in ascertaining the quality of teachers. The teaching profession used to be an enviable calling; it is time, for the sake of the country, to bring back that worthy veneration of the teacher.

Finally, Nigeria must work to achieve true federalism and must respect the time-honoured principle of subsidiarity. A core part of the problem, all this while, has been that no one seems able to do anything without recourse to the federal authority at Abuja, an authority which has clogged itself with a myriad of unachievable functions. Time was, when everything important (from education to health and justice) was well taken care of by local authorities. Things were properly done then and in order, proving that the only way government can truly work is when it is as low as possible and only as high as necessary. May the eyes of those in power in Nigeria today open to this reality.

END

Be the first to comment