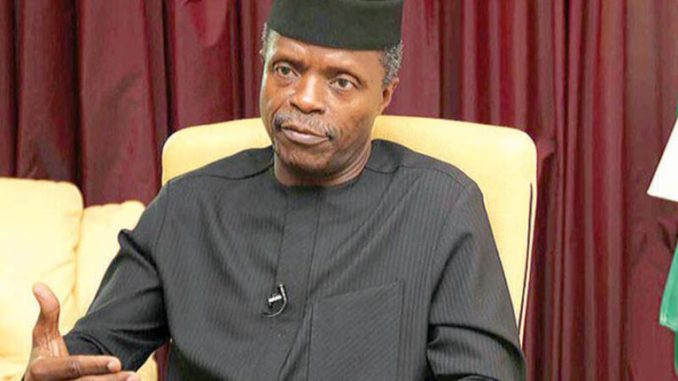

Mass resignation of doctors from the country’s public health institutions is an unwholesome development that further imperils our already fragile healthcare delivery system. Some stakeholders have been raising concerns about this. Now that the Vice-President, Yemi Osinbajo, has joined the lamentation, the Federal Government should spare no effort to halt the drift.

Both federal and state hospitals are afflicted by the scourge. About 800 physicians in the employ of Lagos State reportedly resigned in the last two years. At the University College Hospital, Ibadan, 100 doctors have left this year, just as the crises-ridden Ladoke Akintola University Teaching Hospital in Ogbomoso has lost the services of 200 doctors in 2017. From Kebbi State comes the incredible news that it has yet to employ any doctor, despite several vacancy advertisements, in two years.

These few sketches could provide an insight into the reality in other states of the federation. At issue is the dismal level of job satisfaction that naturally results from poor remuneration, lack of equipment and dilapidated infrastructure.

In Lagos, doctors under the aegis of the Medical Guild allege lack of promotion of its members and the government’s infidelity to the implementation of the readjusted “Consolidated Medical Salary Scale” as agreed on in 2014. The guild’s chairman, Saliu Oseni, said Ikorodu General Hospital, where he works, has so far lost the services of 30 doctors this year. In the wake of a protracted strike over improved remuneration, the immediate past administration sacked 788 doctors in 2012, but later re-instated them. The situation at LAUTECH is more pathetic. Its resident doctors allege that only 28 per cent of their salary is being paid since January 2016. The union’s president, Sebastine Oiwoh, and secretary, Ayobami Alabi, stressed in a statement that 12 months salaries were in arrears.

This mass exit is bad enough, but also worrisome is their exodus to the West that already has an advanced medical system. The United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, Saudi Arabia, Australia and United Arab Emirates, among others, are the preferred destinations. Between 500 and 700 Nigerian doctors reportedly sit qualifying exams annually to practice either in the US or UK. The chairman, Nigerian Medical Association, Lagos State branch, Olumuyiwa Odusote, says about 40,000 out of 75,000 registered Nigerian doctors are practising abroad.

Consequently, those still in the system are overworked and fatigued, conditions that could expose them to avoidable blunders. Whereas the World Health Organisation recommends a doctor to patients’ ratio of 1:600, Nigeria has above 1:4,000. The current drain can only worsen this dire situation.

Indeed, it is a clear and present danger with the result of a recent survey by the Nigerian Polling Organisation in collaboration with the Nigeria Health Watch. Shockingly, it revealed that 88 per cent of doctors were ready to work abroad. About 30 per cent had enrolled for the UK Professional and Linguistics Assessment Board test; another 30 per cent for the US Medical Licensing Examination, while 15 per cent applied for the Canadian equivalent of the examination.

Apparently, federal and state governments have failed woefully to adequately fund health care. Even when funds are provided, or projects funded, the execution is mired in corruption. This was the case with many primary healthcare centres contracts awarded by the last administration. While some were abandoned after full payment had been collected, others could not be located at their claimed official addresses, according to a media survey. There are 10,000 primary healthcare centres billed for federal rehabilitation.

At the tertiary level, the condition is no less agonising. The Association of Resident Doctors in one of the first generation university teaching hospitals, in 2015, decried the horrible state of affairs there: “We carry out surgeries with torch and candle lights following power failure and dysfunctional generators,” they said. “Only the poorest of the poor,” they added, patronise the hospital as a last resort. Yet, the hospital purports to be one of the country’s centres of medical excellence.

The First Lady, Aisha Buhari’s revelation that the Presidential Clinic in Aso Rock, could not treat her because of lack of basic equipment, speaks volumes. Ironically, Nigeria committed itself to a reasonable level of health financing with the 2001 Abuja declaration by African Heads of State to dedicate 15 per cent of their budgets annually to the cause. It is unfortunate that the N340.4 billion for health, which represents 3.9 per cent of the N8.61 trillion 2018 budget, is nowhere close to this benchmark. This explains why no one-stop-shop cancer centre exists in Nigeria, despite the estimated 100,000 cases reported annually. India has 120 of such centres, says Femi Majekodunmi, a medical doctor. Nigeria’s lack of seriousness in addressing the inadequacies in the sector is evident again, in the 10 years it took to pass the National Health Act; and three years after, implementation is a far-cry.

But the country can do better by getting its priorities right. Health is a social policy matter, which developed countries give a great deal of attention, as it touches on the right to life. The NH Act should be made to work without further delay to achieve universal health coverage. By so doing, the life of Wilfred Ugoh, a two-year-old boy with a hole in the heart, could be saved. Doctors treating him have referred his case to an Indian hospital. This is sad because none of our teaching hospitals is well equipped to save him. WHO reminds Nigerian authorities that 2,300 under-five and 145 women of childbearing age die every day. It says, “This makes the country the second largest contributor to under-five and maternal mortality rate in the world.”

However, this burden could have been avoided if its healthcare delivery had been anchored on a robust primary healthcare foundation. This is where Cuba has excelled globally, thus becoming a global role model. Corruption and bad governance are obstacles to Nigeria’s adequate health funding. Many overlapping public agencies with bloated wages and recurrent costs need to be right-sized to cut costs, thereby saving funds that could be channelled to the health sector. Without a healthy workforce, the economy will inexorably be endangered.

END

Be the first to comment