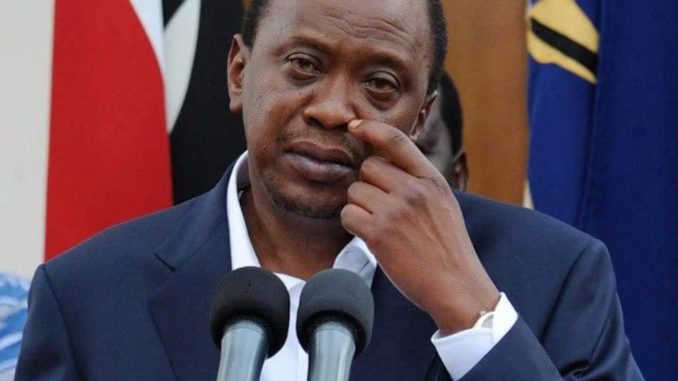

Uhuru Kenyatta’s characterisation of the Supreme Court of Kenya as crooks or scoundrels, and his threat to fix the court once he’s re-elected are vulnerabilities that elections often fail to fix. They are not often enough, on their own, in jurisdictions with multiple fissiparous tendencies to lead to damaging vote loss.

You do not have to be partisan in the debate (on social media, last week) over whether the annulment by the Kenyan Supreme Court (also last week) of the result of the recent presidential election in that country was the first of its kind on the continent, to agree that it was, nonetheless, a landmark event. The annulment by the Babangida administration of the results of the 1993 presidential election in Nigeria was an inbetweener of sorts: final results had not yet been (officially) announced (unlike the one in Kenya); and given that the incumbent government was a military one, it was also a quasi-coup d’état.

Then, there was the military coup that put paid to the first multi-party elections in Algeria (since attaining independence). Concerned that the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) was going to win the December 26, 1991 parliamentary elections, the army set in train a long and bloody civil war. But even then, much of the hope (in Nigeria) around a resolution of the impasse that followed what has come to be known as the “June 12” elections rested on the judiciary. As it has done, now and again, in other jurisdictions where the overweening ambitions of caudillos have regularly threatened the rights of citizens lower down the pecking order.

Increasingly, therefore, across developing economies transiting from authoritarian to liberal democratic governments, much of the emphasis on defence of popular rights is shifting from the previous concern with the conduct of regular elections, and the battery of third party institutions organised to ensure that such elections are free and fair to considerations of the independence of the judiciary. Whereas, previously, the ability to choose one’s government was considered a high-order right, it has become clear that lower-order institutions have a constructive role to play in the enthronement of this right. The vulnerabilities of a democracy are not solely from errors of commission (as in when would-be monarchs interfere with the proper running of the process). There are, increasingly, also threats to governance from the quotidian exercise of the institutions of the state (look no further than Donald Trump’s America). Confirming the fact that the successful management of a democracy is not about regular elections only.

Despite the media focus on the happenings in Kenya last week, in a way, across key swathes of the developing world, courts delivered judgements that point to new levels of maturity in these parts. The constitutional court’s decision in Guatemala to over-rule President Jimmy Morales’s expulsion of Iván Velásquez was simultaneously a clear statement on the boundaries of presidential powers in a democracy, as it was a vote for clean politics. President Morales took exception to the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG)’s — a UN-backed body, which Mr. Velásquez heads — decision to open investigations on the funding of his party, the National Convergence Front (FCN).

…Uhuru Kenyatta’s response to the Kenyan Supreme Court’s ruling fell short of the acceptable. Even in the English language rendition, the narrative around six people putting the kybosh on an election in which millions cast their vote was far from a positive take on the outcome.

In India, the supreme court faced a challenge of a different order. Again, much of the media focus on Indian courts, last week, was as excited about the boost to women’s rights from the ban on the “triple talaq” (which, until the verdict, made it easy for men to divorce their wives by uttering the Arabic word for “divorce” three times), as it was by the emphasis on equality before the law purportedly reinforced by a state court which found Ram Rahim Singh guilty of rape. Of greater moment though, was the Indian supreme court’s finding that “privacy” is a key part of all the many liberties that a democracy argues as basic to our collective humanity. Put this way, there is no stronger let on hubristic government than one where the laws are described and operated with broad attention to protecting individual rights.

Ironically, while privacy is important for the enjoyment of those rights without which our humanity is considerably diminished, if not completely negated, the standards by which this concept must be enforced loosen in their application to those who would govern. Therefore, Uhuru Kenyatta’s response to the Kenyan Supreme Court’s ruling fell short of the acceptable. Even in the English language rendition, the narrative around six people putting the kybosh on an election in which millions cast their vote was far from a positive take on the outcome. It, therefore, mattered that the Law Society of Kenya came out unequivocally on the Kenyan president’s response in Swahili to the court’s decision.

Uhuru Kenyatta’s characterisation of the Supreme Court of Kenya as crooks or scoundrels, and his threat to fix the court once he’s re-elected are vulnerabilities that elections often fail to fix. They are not often enough, on their own, in jurisdictions with multiple fissiparous tendencies to lead to damaging vote loss. Accordingly, failings of this type make the strongest case for strengthening lower order institutions in frontier economies such as ours.

Uddin Ifeanyi, journalist manqué and retired civil servant, can be reached @IfeanyiUddin.

END

Be the first to comment