Daniel Toroitich Arap Moi, Kenya’s president from 1978 to 2002, died on 4 February at the age of 95. He was one of Africa’s most ruthless and uncouth autocrats. Moi was born in September 1924 in a rural Rift Valley settlement as a member of the country’s Kalenjin ethnic group. His herder father died when he was only four, and he attended Christian mission schools, before working as a teacher from 1946 until 1955, when he joined the British-controlled Legislative Council. Moi was one of the founders of the Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) in 1960 to challenge the hegemony of founding Kikuyu president, Jomo Kenyatta’s Kenya African National Union (KANU).

KADU sought to protect the rights of minority ethnic groups by promoting a federal system (“majimboism”). The party was, however, soon co-opted by KANU, and Moi became home affairs minister before becoming vice-president in1967. He was often underestimated as a subservient political lightweight with limited ambitions. After Kenyatta died in August 1978, Moi became president. He was so terrified of the Kikuyu clique around the presidency known as the “Kiambu Mafia” that he fled his home in the Rift Valley. Only slowly did he grow into the role and gain the confidence to run the country. He traversed Kenya promoting unity, released political prisoners, and announced a strategy of Nyayo, vowing to follow in Kenyatta’s footsteps.

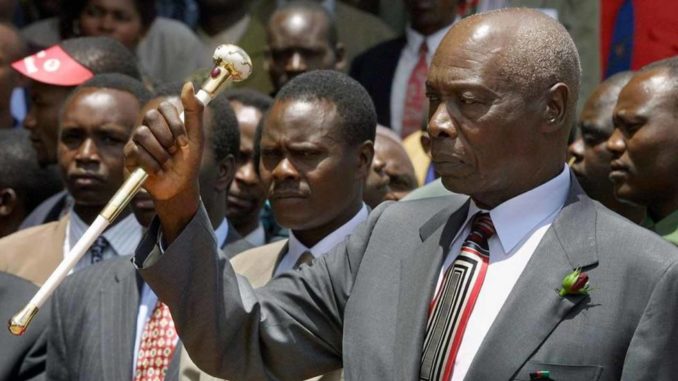

Moi, however, soon became comfortable with the trappings of the autocratic accoutrements he had inherited: his predecessor’s tyrannical robes were made to be worn. He abandoned his previous commitment to federalism for central control. Moi also established a personality cult, with bank notes and coins bearing his image; and universities, schools, roads, and public buildings named after him. Statues were erected in his image. He surrounded himself with compliant cronies and feckless flatterers. He carried the ivory stick so beloved of African autocrats, wielding it as if it had mystical powers. Moi soon declared the country to be a de jure rather than de facto one-party state in July 1982, banning all opposition to his rule.

An attempted coup d’état by the country’s air-force a month later provided him with the opportunity to unleash his iron fist, and he never sheathed his sword. At least 159 people were killed in the subsequent trials.

Marxism was banned as a subject of study at the country’s universities, as the anti-intellectual autocrat launched a vicious assault on the country’s ivory towers. Draconian media laws were passed. Civil servants were forced to join the ruling party. All political opposition was crushed, and a “rule by plot” instituted. There was a clamp-down on the intelligentsia and civil society, with secret police operatives infiltrating these organisations.

A torture chamber was set up in Nairobi’s notorious Nyayo House in which many dissidents were jailed, starved, and killed. Leading intellectuals like Ngugi wa Thiong’o, Micere Mugo, and Alamin Mazrui were hounded into exile. Nobel peace laureate, Wangari Maathai, and other civil society activists were violently persecuted for protesting against human rights abuses and corrupt efforts to turn Uhuru Park into a skyscraper. Moi’s regime reached its nadir when Luo foreign minister, Robert Ouko, was murdered in 1990. A subsequent investigation revealed Ouko had been killed in one of Moi’s presidential residences, probably with the president himself present.

Moi tightened his grip on key institutions such as the rubber-stamp Parliament, judiciary, and security services. He clamped down harshly on independent media. The end of the Cold War and street protests eventually culminated in multi-party politics, at the cost of 1,000 fatalities. Moi won elections in 1992 and 1997 through bribery, intimidation, violence, and rigging, as politics became a means of waging war by other means. He won respectively just 36% and 40% of the vote against a divided opposition: far from the over 90% which contemporary autocrats in Egypt and Rwanda award themselves. His weapon of divisive ethnic violence in the hands of his successors, however, came within a whisker of plunging the country into civil war in 2007. The country’s diabolical political wizard had released the ethnic genie from the national lamp. Kenya’s economy, which is East Africa’s largest, stagnated under Moi’s rule. Graft (“magendo”) became a by-word of the Moi regime, as he hollowed out the country’s major institutions.

The “Anglo Leasing” scandal of the 1990s involved state contracts being awarded to fictitious firms. The Goldenberg scandal of the same epoch involved a scheme in which the government supposedly subsidised gold exports to raise foreign currency. The fraud allegedly involving Moi, cabinet members, and crooked businessmen cost the country over 10% of its Gross Domestic Product. In 2007, Wikileaks exposed secret trusts, shell companies, and shadowy front men in corruption that was later estimated to have cost Kenya $4 billion.

Following in the footsteps of Kenyatta, Moi reportedly stole large tracts of public land, awarding some to ministers, mandarins, and military brass hats as part of political patronage. As Marxist regimes spread in neighbouring Ethiopia and Tanzania, the West regarded Kenya as a bulwark against such ideological influences.

Moi thus became a strategic ally during the Cold War. American and British troops were hosted, and like another Western Cold War client, Zaire’s Mobutu Sese Seko, Moi presented himself as indispensable to holding the country together, even as both dictators’ cynical manipulation of political divisions made such instability inevitable once they had left power. As he was pushed by the West to adopt a multi-party political system, an embittered Moi felt betrayed by his former patrons for whom he had outlived his strategic usefulness. Moi hosted a mediation process on Sudan which eventually culminated in the independence of South Sudan by 2011. He was also involved in the successful effort to revive the East African Community by 2000.

Having left office in 2002 after 24 years in power, Moi retired to his sprawling Kabarak farm – one of seven homes – in Nakuru county, rarely making public appearances. He did, however, continue to influence national politics, with president Mwai Kibaki also appointing him Kenya’s Special Peace Envoy to Sudan in 2007. Moi married Lena Bomett, a fellow teacher, in 1950, but they separated in 1974 (she died in 2004). They brought up eight children together, and a son Gideon is currently a Kenyan Senator.

In his final years, the wheelchair-bound Moi’s health began to fail and there were reports of dementia, water in the lungs, and knee problems. He remained a life-long member of the African Island Mission Church, and often liked to portray himself as an ascetic, devout Christian who shunned alcohol and material possessions, and condemned mini-skirts and hippies. Paying tribute to his political mentor, Kenyan president, Uhuru Kenyatta – son of the founding president – noted that “Daniel Arap Moi ran a good race, kept the faith, and now he is enjoying his reward in heaven.” It is, however, unlikely that the Almighty will so easily swing open the gates of Paradise to such a ruthless autocrat. Based on his ghastly 24-year record in power, Moi is more likely to end up going the other way.

Professor Adebajo is director, University of Johannesburg’s Institute for Pan-African Thought and Conversation, South Africa.

END

Be the first to comment