It has been over two months since Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari issued Executive Order 6 of 2018. The stated purpose of the Executive Order was the “preservation of suspicious assets connected with corruption and other relevant offences.” In furtherance of this, the Order empowers the Attorney-General to apply all available lawful and statutory means to preserve assets connected with corruption from being dissipated, pending the final determination by a court of any corruption-related matter against the owners of such assets. This is to be done in collaboration with other named law enforcement agencies.

In rationalising the order, the government noted that its implementation would deprive corrupt individuals and those connected to them from using the proceeds of their illicit activities to unduly allure, intimidate or pervert investigative and judicial processes. This is in addition to the broader objective of preventing such assets from being transferred, withdrawn or otherwise dissipated.

Against the backdrop of such vital necessities for anticorruption efforts in Nigeria, the large number of views expressed in opposition to the Executive Order was somewhat surprising. Apart from a few civil society organisations that expressed support for it, most prominent voices in the anticorruption and human rights space in the country criticised the Order for violating constitutional principles of separation of powers and human rights and demonstrating abuse of executive powers.

In similar vein, there is currently a suit before the Federal High Court Abuja seeking the nullification of the Order for being unlawful, unconstitutional, null and void. Whilst it is hoped that the court will render a decision that will finally put the legal concerns around the Order to rest, it is necessary to put in context the broader questions arising from the issuance of the Order – and the reactions in its wake – for anticorruption efforts in Nigeria.

Overly legalistic analysis is not always pragmatic. A central theme of the criticisms of Executive Order 6 is the concern over its potential to violate human rights and encroach on the doctrine of separation of powers. Whilst it is important to protect these fundamental pillars of our democracy, it is arguably more crucial in the context of countries in the global south to ensure this is done in a manner that promotes the “good government and welfare” of the people of Nigeria. As stated in the preamble to the 1999 Constitution, this is the ultimate purpose of our democracy.

These principles would mean nothing if the safety and welfare of the people are in jeopardy. Very few things constitute a more potent and continuous threat to the achievement of this objective in Nigeria than corruption. Our analysis of anticorruption initiatives must therefore always seek to achieve a balance between promoting the welfare of the people and the protection of the principles of democratic practice.

In any case, a considered interpretation of Executive Order 6 shows that its wording repeated reiterates the need to respect the same constitutional principles which critics claim that it violates.For instance, Section 1(a) requires the use of “lawful and statutory means, including seeking the appropriate court orders” in enforcing the Order. Similarly, Section 3(i) empowers any person who is concerned about an infringement of his rights because of provisions of the Order to apply to a competent court for redress.

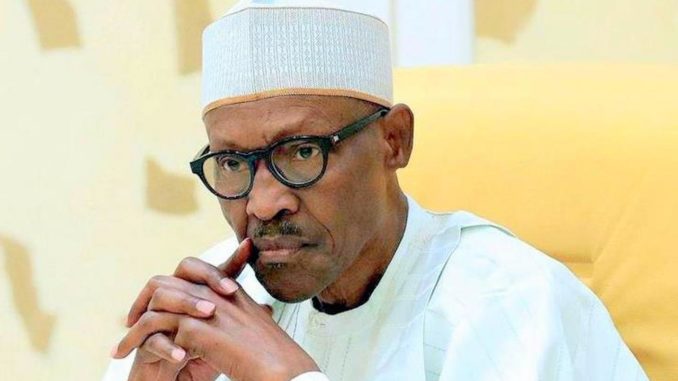

It is vital to separate the reform initiative from the initiator. Even though there have been consistent calls for the institutionalisation of anticorruption processes in the country, most analysis of Executive Order 6 concentrated on the person and antecedents of President Buhari than the object and content of the Order.This does not encourage objective analysis of policies and initiatives and is counterintuitive to the demands for institutionalisation of anticorruption efforts in the country.

We cannot enrich our democratic experience as a country if we do not demonstrate faith in the ability of its systems and mechanisms to ensure that policies on paper work as intended. It is vital and more beneficial in the long run, to look at reforms objectively on their merits and make use of the vast legal safeguards in place in a democratic setting to ensure their unprejudiced implementation. Unfortunately, in the case of Executive Order 6, the personal history of the President and his ‘tendencies’ were overly used by many as the basis of criticism, even though they admit the obvious expedience of the Order.

Whilst there are valid questions about the position of the current government on certain human rights issues, the action of analysing the initiative through the actions of the initiator robbed an otherwise good anticorruption initiative of much-needed public support at its inception. Regrettably, the effect of this for the broader anticorruption effort in the country is likely to be long-term and will surely outlive the current administration.

Avoiding multiple institutions should not mean less mechanism. The multiplicity of anticorruption institutions in Nigeria and their often-overlapping jurisdictions is an issue that remains unresolved. Hence, arguments for the anticorruption regime in Nigeria to make current institutions more effective rather than creating fresh ones is understandable. This must however be separated from mechanisms dealing with corruption.The multifaceted and systemic nature of corruption in Nigeria means that relevant stakeholders must continue to innovate and leverage new instruments and frameworks to address corruption. Executive Order 6 provides a unique mechanism to address a perennial problem with anticorruption efforts in Nigeria: the dissipation of assets by suspects in corruption cases and the use of such assets to frustrate the criminal justice system.

In the light of the obvious safeguards stated in the executive order, and those available through the broader constitutional framework in Nigeria, perhaps the interest of civil society and other stakeholders involved in addressing corruption in the country will be best served by supporting this innovative mechanism. This can be done whilst cautiously monitoring its implementation to check abuse. As we await the decision of the courts, we must ensure that these valuable lessons endure.

Dr. Matthew is director Research and Policy, ANEEJ.

Be the first to comment