It is now more than six months since Nigeria reported its index case of Coronavirus.

On March 23, the country closed its airports to all international flights and commercial operations, for a month, in the first instance, with the exception of emergency and essential flights. Previously, in August 2019, the country had shut down its land borders in an attempt to check smuggling. With COVID-19, those borders remained closed. On March 30, 2020, at 11 pm, Nigeria began the first phase of its COVID lockdown – initially for a period of 14 days in Lagos and Ogun States and the Federal Capital Territory. Gradually, the entire country was locked down. Inter-state movement was restricted. Curfew was imposed. Six months later, where are we? How safe are we as a people and as a country? What future challenges do we still need to worry about? What has been the impact of COVID-19 on our lives?

Today, as at the time of this writing, Nigeria has a total number of 56, 256 confirmed cases, 44, 152 discharged persons and 1, 082 deaths. These figures apparently do not reflect the true situation of the COVID-19 pandemic in the country. The situation is most likely to be worse, in part because Nigeria continues to struggle with testing and tracing of COVID-19 cases. After an initial problem with testing kits, reagents and the scarcity of basic medical infrastructure, Nigeria finally made its way to a point where, over the months, 35 states of the Federation and the Federal Capital Territory could now boast of isolation and treatment centres. The number of laboratories also gradually increased. Nigeria can now test 15, 000 samples per day and so far over 400, 000 tests have been conducted. As a proportion of the country’s population of 200 million, that is a very small percentage indeed. Countries like Ghana, South Africa, Morocco, Senegal and Algeria have done much better. Part of the problem is that Nigerians are reluctant to embrace the option of voluntary testing even at government-owned centres where the test is free. Ordinarily, a COVID-19 test in Nigeria is about N54, 500. Treatment is expensive and definitely out of the reach of the poor who prefer alternative options: resort to magic, spiritualism or an unproven conviction that the virus only affects the rich and privileged.

These are some of the reasons why the reported data may not be exact. Nor is the data on COVID-19 exact anywhere in the world due to differences in national capacity and tracking systems. In that wise, even the reported global figures of over 29 million cases, 929, 263 deaths, and over 21 million recoveries can be subjected to further questioning. Compared to other parts of the world however, African countries have done relatively well, with perhaps the exception of South Africa which has the highest number of cases, and which by the way, has conducted more COVID-19 tests than any other country in the continent. Africa doing well, can be explained on only one ground: the prediction that Africa would be worst hit by the pandemic has not come to pass. Ms Melinda Gates had much earlier in the year expressed the concern that African countries could end up like Ecuador with COVID-19 corpses littering the streets, overcrowded hospitals and cemeteries and a public health emergency that would overwhelm the continent. This has not happened. Scientists are therefore left with a puzzle: Why is the virus more devastating in some parts of the world, and yet so mild elsewhere? Is there a genetic or zoonotic explanation for this? Or could it be that the worst is yet to occur in Africa where health infrastructure is poor, and the leaders listen more to prayer warriors and shamanists and treat scientists with disdain?

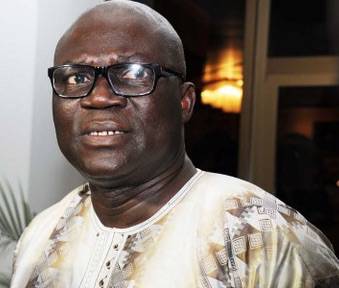

Reuben Abati

Six months later in Nigeria, life has more or less returned to normal. By May 4, the Federal Government announced a gradual and phased easing of lockdown measures. A second phase was soon announced on June 29, for a period of 4 weeks. On July 27, this was further extended. By the end of August, Nigeria was back on its feet. Now, places of religious worship have reopened. Schools also. Government advisers insist that the country needs to strike a balance between protecting lives and livelihoods and getting the people back to work, given the negative impact of the lockdown and restrictions in virtually every sector of the economy. For the most part, Nigeria simply adopted the COVID-19 guidelines and protocols recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the African Centre for Disease Control. The only problem that I have seen is that as the country re-opens, our people are now behaving as if indeed COVID-19 is gone. Widespread fear greeted the initial report of the pandemic. Panic followed. Nigerians no longer seem to worry.

In Lagos, which for months was the epicentre of the pandemic, and still the state with the majority of cases, the people no longer wear face masks. They have bluntly refused to take responsibility. Commuter buses are routinely filled to capacity. Stores, supermarkets, banks and offices still insist on the “No Mask, No Entry” policy but really, nobody is afraid anymore. In the rural parts of the country, it is as if there was never anything called COVID-19: the deadly virus. Go across the country. People now shake hands. Hug each other. Hold parties. Eat from the same plate. Politicians are beginning to criss-cross the country, and they are not showing good example. In states where there are scheduled elections, and campaigns are on-going, nobody observes any form of physical distancing. I asked a prominent politician why he does not consider it necessary to insist on COVID-19 protocols during his campaign rallies. He confessed that it would be difficult to do that in politics. People are just tired. COVID-19 fatigue may in the long run prove to be worse than the virus itself. Meanwhile, no flattening of the curve has been observed.

There is need for caution, and perhaps this is where efforts need to be concentrated going forward. Nigerians and other Africans may just have been lucky so far with COVID-19. Nonetheless, it is better to learn from other countries and not assume that we are entitled to some form of scientific or divine immunity. As Nigeria fully re-opens, the government should not rule out the possibility of ordering a fresh lockdown in parts of the country should there be a sudden surge in infections.

Today, many countries that opted for the lifting of the lockdown are now introducing stricter measures as they experience a second wave of the virus – as in India, Israel, France, Austria, South Korea, Germany, or a third wave – as in Hong Kong. For example, when Israel which had proven capable of containing the virus in March, chose to re-open its schools in May, its COVID-19 infection rates escalated rapidly to become one of the world’s highest per-capita rates. Israel had to shut down schools immediately and reintroduced stricter measures. Five times, in the course of the pandemic, South Korea tried to reopen its schools. When it eventually did so in May, it shut down the schools again within days after a sudden spike in cases. Uruguay and Japan have done much better with the easing of lockdowns. But not Italy, which has now chosen to re-open its schools despite the rise in infections.

The UK is another useful example. Faced with a sharp rise in the R-Number (that is the rate at which infection spreads from one person to others), the UK has locked down some communities. It has further introduced “the Rule of Six” which forbids the gathering of more than six persons. This rule does not exempt children under 12 in England, but it exempts children under 11 and 12 in Wales and Scotland respectively. The UK has also introduced COVID Marshals who are empowered to break up any group of more than six. Violators are liable to a fine of 100 pounds per member, and double fines for repeated offences up to 3, 200 pounds. Neighbours are also required to report any suspected breaches to the authorities. What the UK has done is to remind the people that the troubles of COVID-19 are far from over; every one must take responsibility. We need similar measures here in Nigeria. We need COVID-19 Marshals. Gatherings should be restricted. People should be made to pay fines for failing to wear masks or observe social distancing. This is probably the only way to remind Nigerians that the war against COVID-19 has not yet been won. The COVID-19 Marshals can be volunteers who will liaise with the police and relevant authorities. Now that the schools are re-opening and international flights have resumed, there is greater need for vigilance.

One key thing government needs to deal with: the misconception that there is already a cure for COVID-19. The other day, a Professor, a man I respect a lot, told me that there is now in Nigerian markets a COVID-19 vaccine, which is approved for sale only in Africa. I told him this is not possible because the known fact is that there is no approved COVID-19 vaccine anywhere in the world yet. What we have is a global race for the vaccine with over 100 possible vaccines still undergoing various stages of clinical trials. He was adamant. He said he was sure of his information. He asked me not to listen to international politics about COVID-19. I was stunned. I wanted to ask him to show me a picture of the said vaccine or provide more concrete evidence. I didn’t want to appear rude. I kept quiet. But if indeed some Nigerians are promoting a COVID-19 vaccine, unknown to the authorities, that would be very sad indeed. Even the smartest scientists in the world are still busy trying to understand the virus. It could take years or months before they can record a breakthrough. Last week, AstraZeneca, the British-Swedish pharmaceutical company collaborating with researchers at the University of Oxford, had to suspend its drug trials when a volunteer who had taken a dose of the experimental vaccine reported severe side effects. The trials have now re-commenced after that deliberate pause. The gold standard in vaccine trials and authorization is safety. Nigeria must ensure that nobody smuggles fake COVID-19 vaccines or drugs into the country. Low-income, developing countries face multiple jeopardy in the face of COVID-19. The main leadership challenge is to protect the people from themselves.

More than anything else, COVID-19, six months later, has exposed our vulnerabilities as a country and as a people. Nigerians have often paid lip service to the need to diversify the country’s economy away from over-dependence on petroleum resources which account for the bulk of the country’s revenue. With the distortions in global demand and supply, caused by COVID-19 lockdown and restrictions, and lower demand for crude, Nigeria suffered a revenue crisis. Pre-COVID, the country’s economy was weak. COVID worsened everything. Nigeria had to revise its 2020 budget twice. We also had to go a-borrowing, cap in hand. The country’s CPI (inflation) rose up to 12.82%. Unemployment figures shot through the roof. By Q3 2020, Nigeria will be in recession, a second time in 5 years. There are projections inflation could hit 14% plus by December 2020. There has been so much talk about recovery by 2022, but nobody is certain about the nature of that recovery: V, W, U, or L–shaped.

Even with the best of intentions, the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) has not been able to save the Naira or resolve liquidity problems. The government has been very eloquent about what it can do for the people: palliatives, stimulus packages, economic sustainability programmes. intervention funds but official policies have been at best ambivalent. The recent removal of fuel subsidy, and the hike in electricity tariffs have both further eroded the average Nigerian’s purchasing power. Questions have therefore been raised about leadership and policy choices. Consider this: In other parts of the world, governments have duly acknowledged in the face of the pandemic, the heroism of frontline healthcare workers and first responders. Here in Nigeria, amid COVID-19 pandemic, health workers have in the last six months declared industrial actions against states and the Federal Government. They are unhappy that government does not consider it necessary to pay them salary arrears and COVID-19 hazard allowance. Only two states- Nasarawa and Enugu- have reportedly paid up to date. Last week, the National Association of Resident Doctors (NARD) went on strike. The doctors had to be mollified. This week, the Joint Health Workers Union of Nigeria (JOHESU) also embarked on strike over non-payment of COVID-19 allowances. Why pick fights with medical doctors and other frontline care providers in the middle of a global health crisis? Why downplay the crisis of hunger and poverty in the land?

It is not all gloom though. ThisDay newspaper recently published a list of heroes and amazons of COVID-19 in Nigeria. The list includes institutions, private sector figures, the Presidential Task Force on COVID-19, medical practitioners, and others who have contributed in cash and in kind and worked hard to manage the spread of the virus. When all this is over, it would be necessary to also compile a list of COVID-19 villains. I am keeping notes.

END

Be the first to comment