Despite contending with widespread poverty and yawning infrastructure deficit, requiring a sagacious financial management for survival, Nigeria still operates an opaque fiscal system that creates room for massive abuse and malpractices. A typical example is contained in a recent report by the Nigeria Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and Trust Africa, which revealed that the country loses between $15 billion and $18 billion annually to illicit financial flows.

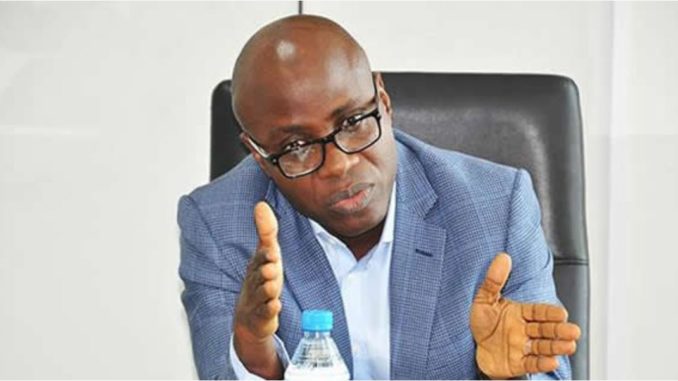

Typically, this is a damaging internal haemorrhage that should inspire some soul-searching from a country that is in desperate need of foreign investment, yet is exposed to IFFs. By any African standard, $15 to $18 billion is a tidy sum of money that could impact positively on any aspect of human life if judiciously applied. As the Executive Secretary of NEITI, Waziri Adio, said, one could only imagine what difference that amount of money “would have made to all the things that matter to us in this country.”

On a yearly basis, NIETI, the Nigerian arm of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative, a global standard for the good governance of oil/gas and mineral resources, comes up with damaging reports about the opacity in the operations of Nigeria’s oil industry. Yet, no concrete action is taken to address the corrupt practices. It has not come as a surprise that NEITI has been able to trace 90 per cent of the IFFs to the country’s oil sector. It is a sector that provides more than 90 per cent of Nigeria’s foreign earnings and needs to be thoroughly cleaned up if the country is to enjoy the benefits of her natural resources.

IFFs, according to the World Bank, refer to the cross-border movement of capital associated with “illegal activities or, more explicitly, money that is illegally earned, transferred or used that crosses borders.” Such activities include smuggling and trafficking in people, drugs and minerals – like the Nigerian oil that Chatham House, a United Kingdom-based think tank, once said was being stolen on an “industrial scale,” and the gold that is illegally mined in Zamfara State and other parts of the country.

While Nigeria may not be taking IFFs as seriously as she should, the practice is commanding world-wide attention because of the challenges it poses to the economy and many other aspects of life. Among other things, the International Monetary Fund identifies the drain in foreign reserves, lower tax receipts and reduced government revenues as some of the negative effects of IFFs.

Needless to say, these are also among the biggest problems facing the Nigerian economy today, as the country continues to lament the failure to capture many high income earners in the tax net. Figures released by the National Bureau of Statistics show that only 14 million out of 69 million taxable Nigerians currently pay tax. Nigeria also faces a lot of pressure on her foreign reserves as the Central Bank of Nigeria tries all the tricks in the book to preserve the country’s foreign exchange stock from being drastically drawn down. The CBN also faces the challenge of defending the Naira to avert the situation currently being experienced in Venezuela and Zimbabwe.

Although a global phenomenon, developing countries remain the biggest victims of the economic destabilising effects of IFFs. A Global Financial Integrity report says, conservatively, an estimated $1.1 trillion left developing countries in IFFs in 2013 alone. Of course, the world has continued to witness a staggering rise despite the numerous money laundering regulations introduced to check such practices. The GFI, a stakeholder in efforts to curtail IFFs and “enhance global development and security”, identifies IFFs as a major culprit that strips “developing nations of critical resources and contributes to failed states.”

Nigeria has for many years remained a prominent victim of the illicit financial outflows in Africa. While NEITI, on a yearly basis, churns out reports on the lack of good governance in Nigeria’s extractive industry, the National Assembly, saddled with the oversight duty over such matters, hardly spares a thought for a matter of such national importance. But the report of the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows, which was set up by the African Union Commission/United Nations Economic Commission for Africa, headed by a former President of South Africa, Thabo Mabeki, said in 2015 that Africa was losing $50 billion yearly to IFFs, with Nigeria contributing 30 per cent of it. The $50 billion has now risen to $80 billion.

If Nigeria is desirous of an “accelerated and sustained development, relying as much as possible on her own resources”, then a lot needs to be done to reduce illicit flows, according to the Mbeki panel report. This includes exhibiting the political will by the government to ensure that the anti-money laundering laws in the country are ruthlessly enforced so that monies, whether legitimately earned or proceeds of criminality, do not leave the country illicitly.

Besides, the World Bank says that efforts should be redoubled to make sure that those who should pay tax do so, so that there would be less free money to be transferred illegally. There should also be cooperation with other countries to ensure that when such money is taken out, it is repatriated and the culprits are punished. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries said between 2010 and 2012, $147 million was returned to countries where the money was transferred from, while $1.4 billion was frozen. It is difficult to carry out such transfers without the involvement of money deposit banks. So the CBN has to strengthen its regulations so that such activities, which are tantamount to economic sabotage, do not take place undetected.

END

Be the first to comment