The Presidency and all agencies connected to the CJN’s case need to read between the lines of our fragile union in Nigeria and be well advised on decisions that could tip the pot, especially at a time like this, so close to elections.

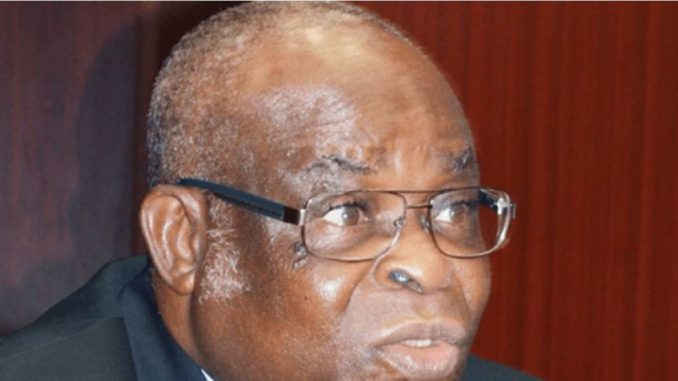

Nigeria is a country of many possibilities. Anything can happen. Even things that were hitherto not thinkable in this planet could just occur. One of such possibilities happened last week when the Code of Conduct Bureau (CCB), dragged the sitting chief justice of Nigeria (CJN), Walter Onnoghen, to the Code of Conduct Tribunal (CCT) over the non-declaration of asset. It marks the first time a sitting CJN will be arraigned in court. It also marks the second time, in this administration, that senior judicial officers would be subjected to legal action without recourse to the National Judicial Council (NJC), the disciplinary arm of the judiciary.

The action against Onnoghen is predicated upon a petition submitted to the CCB by the Anti-corruption and Research-based Data Initiative (ARDI), a civil society group. Although Onnoghen’s chairmanship of the NJC may have presented minor complications if the Bureau had reverted first to the NJC, yet its decision to proceed straight to arraignment presents much bigger complications; and it is not all legal in nature. As it is, there are legal and political aspects to the ensuing controversy.

Legally speaking, the move by the CCB is a curious case. The CCB’s action at the CCT touches on the discipline of judicial officers, an area which the NJC claims superceding, or in the least, supervisory, powers. Paragraph 18 (1) and (2) of Part I of the Fifth Schedule of the 1999 Constitution, as amended, grants the tribunal the power of punishment of public officers for offences in contravention of the Code of Conduct, including matters related to declaration of asset. However, paragraph 21 (b) & (d) of the Third Schedule to the Constitution grants the NJC power over the discipline of judicial officers. As such, there is a question of which power supercedes the other.

Also, it appears that the ultimate aim of the action against Onnoghen is to prosecute and remove the CJN from office. Although the Constitution authorises the CCT to remove public officers as a disciplinary measure, however in section 292 (1) (a) (i), it specifically mentions the CJN as part of a cadre of public officers who can only be removed from office by the president, acting on an address by two-thirds of the members of the Senate.

Leaving the legal aspect for the determination of competent authorities, there are political ramifications of the arraignment of Onnoghen that are disturbing. With elections only weeks away, a move on the head of the judiciary cannot but have political gears grinding, with allegations of ill-motive being shouted from the roof tops by opposition parties.

Nigerian law dictates that specific provisions, as in section 292, supercedes general provisions or references, as in “public officer” in paragraph 18 of Part I of the Fifth Schedule to the Constitution. Although paragraph 5 of Part II of that schedule lists the chief justice of Nigeria as one of the “public officers” referred to in Part I, the list also includes the president, who, for obvious reasons, cannot be subject to the authority of the CCT. One can argue that there are reasons that exclude the CJN from its authority as well.

Then there is the question of the 2017 judgment in the case of Nganjiwa v F.R.N, which has been cited against CCB’s action by some legal practitioners. In that case, the Court of Appeal held that any question of misconduct against a judicial officer is actionable only after the NJC has acted on it and removed the judicial officer. Professor Itse Sagay, chairman of the Presidential Advisory Council on Anti-Corruption, has argued that the issue of declaration of asset is not a matter that arose “in the course of duty”. Irrespective of his view, Professor Sagay continues to display shockingly misguided utterances for a supposed legal luminary, when he seemed to encourage disregard of the Court of Appeal’s decision in any case, even as it remains binding.

When the justices of the Supreme Court were raided, arrested and some arraigned by the Department of State Services (DSS), in 2016, the NJC decried the usurpation and disregard of its authority. It stressed the importance of going through the NJC in every matter involving a judicial officer, as a condition precedent to any further legal action. It now seems that NJC’s statement and warning have gone unheeded in the worst possible way. Some lawyers thought that the Nganjiwa judgment provided some cover for NJC’s authority, but the limitations of that judgment are now being clearly tested in this matter. With all the uncertainty, only judicial interpretation can resolve the pressing questions.

Leaving the legal aspect for the determination of competent authorities, there are political ramifications of the arraignment of Onnoghen that are disturbing. With elections only weeks away, a move on the head of the judiciary cannot but have political gears grinding, with allegations of ill-motive being shouted from the roof tops by opposition parties. Adding to the precarious timing of the petition was the seeming reluctance of the president to confirm Onnoghen in the first place. His confirmation was left till the 11th hour, with the vice president then almost hurriedly having to send a nomination to the Senate for confirmation. Not only that, the executive secretary of the ARDI, Dennis Aghanya, who submitted the petition against Onnoghen, has now been linked to the president. Apparently, he was chairman of President Buhari’s Congress for Progressive Change (CPC), before it merged into the All Progressives Congress (APC), with other parties.

The important issue is not so much about the executive picking fights with the judiciary, but about constitutional loopholes that should not be exploited in the worst possible manner… It is therefore imperative that these overlapping functions arising from the Constitution be thoroughly handled when next there is an amendment.

Although all of the connections above are mere conjecture, these have attracted enough attention to cause the Niger Delta governors to call an emergency meeting. Also, it has made the dormant militants of the area to raise their heads from their sleeping state to issue threats. Whether intended or not, the political backlash was always going to be severe in an atmosphere where a long-serving and diligent official in the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC) is being castigated in a harmless capacity within the Commission. The Presidency and all agencies connected to the CJN’s case need to read between the lines of our fragile union in Nigeria and be well advised on decisions that could tip the pot especially at a time like this, so close to elections.

The polity is being held together at the seams by what remains of our common decency as Nigerians and the belief in a better future. Decisions that stir the boiling underbelly of tribalism and ethnicity in our fragile union can easily lead to unwholesome consequences at this pivotal time, so close to elections. One is not saying that where there is a clear case of misconduct, it should not be acted upon, but where the question of due process of law is shrouded in uncertainty, there is a greater duty to maintain public peace and confidence in the system than there is to enter into expedited action against senior judicial officers.

There are many talking points, but none is greater than the fact of the damage already done to the image of the CJN. Details of his accounts have been made public and there is no taking back the impression created by the manner of deposits of foreign currencies in his accounts. The year 2011 when the deposits were made was also an election year, and this adds to the suspicions about the financial activities in his accounts. In a profession where the slightest inference of misdeed is catastrophic, the damage has already been done to the CJN. While the legal community has gone up in arms to protect its own, and the CJN’s kinsmen have rallied around him, let us not lose focus of the fact that judicial officers are held to the highest standards and there are indeed questions to be answered by the CJN.

The important issue is not so much about the executive picking fights with the judiciary, but about constitutional loopholes that should not be exploited in the worst possible manner. Had Bukola Saraki, the Senate president, been found guilty of his own case before the CCT, the same issues would have arisen when it comes to what the tribunal has the power to do. It is therefore imperative that these overlapping functions arising from the Constitution be thoroughly handled when next there is an amendment.

For comments, send SMS (only) to 08058354382.

END

Be the first to comment