The 2016 US presidential election effectively began on Monday, and as usual it was with an atypical form of balloting: the Iowa caucuses. In every other state, people go to the polls to cast votes for their choice of a party candidate. In Iowa, neighbourhood residents gather in auditoriums or halls and debate the options before casting their votes at the respective “caucuses.”

The strongest case for caucusing is that it bridges the gap between two extremes for selecting candidates. In one extreme, aristocrats select candidates, with or without the facade of popular choice. In the United States, it was known as the “smoke-filled room” approach, a tribute to an era when old fogies discuss the options behind closed doors while whiffing on their cigars.

To a considerable extent, that is what is still practised in Nigeria, sans the cigar. It is emblematic of party-oriented democracy in which people vote for candidates because party chieftains chose them. Former President Goodluck Jonathan was a beneficiary of this system, as was Muhammadu Buhari, though to a lesser extent.

In the United States, the rise of television as a medium of politics and more recently the rise of social media drastically reduced the clout of parties in the selection process. Political stars are now readily born on television, with or without the blessings of the party hierarchy. And so more than ever before the choice of candidates rests on the atomised decisions of individual voters. That is the other extreme.

The assumption of such voting is that the average person makes rational choices. But we all know better. Walter Lippmann, the pioneer American journalist and social critic, certainly made a compelling case to the contrary in the 1920s. And therein lies the value of caucusing. It provides a formal forum in which people discuss candidates’ merits before casting votes. It does not guarantee the right outcome, but it is a more promising approach than the alternatives.

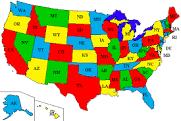

But then the Iowa caucuses often award victory to candidates who end up not winning their party’s nomination, let alone the general election. The mediocre record as a political vane has been attributed largely to the fact that Iowa is not representative of the country. It is more rural, more Caucasian, and religiously more conservative than most states.

But there could be another reason: the dynamics of caucuses. In group dynamics the most outspoken and articulate members exercise disproportion sway over others. And the most outspoken also tend to be the most passionate and hence more extreme.So caucuses would tend to favour candidates that bring particular characteristics, and those are often not the candidates with the most national appeal.

That was largely illustrated by the results of Monday’s caucuses. In the Republican caucuses, three of the Top 4 finishers are all rebels or unconventional candidates. The first-place winner, Senator Ted Cruz, is so uncompromising in his politics that virtually all of his Senate Republican colleagues rue his candidacy. He once single-handedly filibustered a Senate session, using a legislative loophole.

The second-place winner, Donald Trump, is an even more improbable candidate. He is coarse in rhetoric, abusive of rivals, and incendiary in policy pronouncements. He has said that illegal Mexican immigrants are rapists and Muslims should be kept from entering the United States. His ranting even got the British Parliament to consider banning him from ever entering the country.

Inevitably, Trump has become a favourite subject of comic spoofs. Problem is that he sounds so much like parody that there is little difference between the spoofs and the reality.

Ben Carson, the acclaimed surgeon turned politician, came a distant fourth in the caucuses. At some point, he was neck-to-neck with Trump, who was far ahead of others in the crowded Republican field. That inspired me to wonder in this column whether another black man would succeed Obama.

However, the column was hardly in print before a stream of improbable claims by Carson began to surface. Among them were that the Egyptian pyramids were built by Moses to store grains and that Obama’s Affordable Healthcare Programme is the worst thing to happen in the United States since slavery. It quickly became evident that dexterity in the surgical room is not an evidence of an astute mind.

In the Democratic Party’s caucuses, Senator Bernie Sanders relied on the rhetoric of “democratic socialism” to surge to a virtual tie with Hillary Clinton. Until now, Republicans used the socialist tag as daggers against their Democratic opponents. Who would have guessed that a major candidate would run on the socialist platform and come close to winning the first primary, albeit the Iowa caucus? It is a sign of the times, the growing resentment of corporate greed and widening income gap.

With his passion and idealism, Sanders sounds like a throwback to a long past era. Clinton has duly dubbed his idealistic programmes a “pie in the sky” that will go nowhere. It is a line that Republicans will gleefully borrow — and repeat like a broken record — in the unlikely event that Sanders wins the Democratic nomination.

Incidentally, though the Iowa caucuses do not have an excellent record of predicting the outcome of the national elections, they have an impact far beyond the size of America’s 30th state in population. Good performance in Iowa invariably boosts the candidate’s national stature and attracts donors. It is seen as evidence that the candidate has what it takes to win it all.

This clout has caused resentment by larger and otherwise more influential states. Some have taken steps to move their primaries ahead of Iowa’s.But Iowa has vowed to do whatever it takes to retain the privileged position.But if the other states move in concert to remedy the political anomaly, Iowa cannot stop them. One of the options being considered is to have multiple states hold the first primaries. Perhaps, more states would adopt the caucus system.

The main obstacle to redressing Iowa’s vastly disproportionate clout is not Iowans’ objections. It is that American political traditions don’t readily change.

END

Be the first to comment