Yes, thank you, Isidore, for giving us somebody to treasure. Generous, inspiring teacher, perceptive writer, scholar of no mean repute, you enrich us all with your combination of intellect and integrity, acute seriousness and lightness of being, seamless sense of humour and sizzling vivacity, a consistently compassionate temperament and humane disposition. You have called Life by its rightful name. Its answer is robustly positive and eternally assuring.

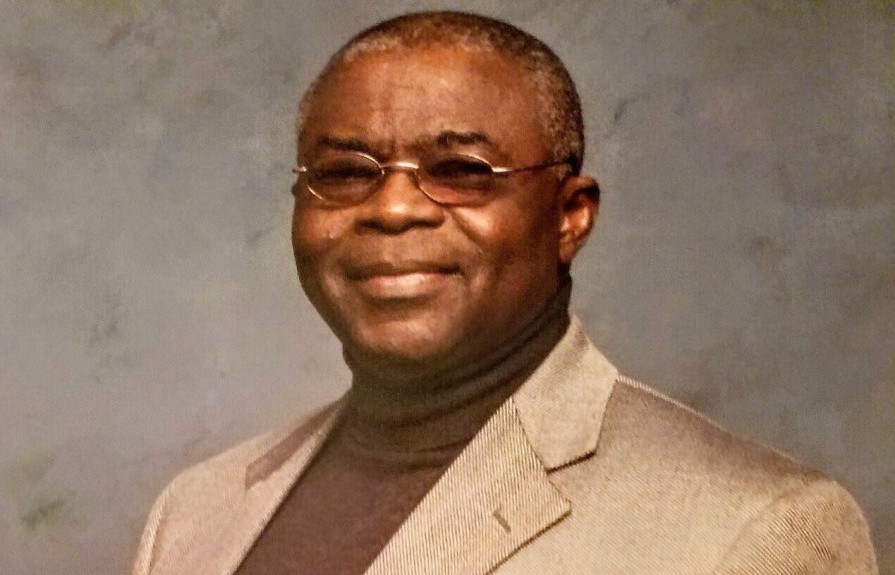

The loss is hard to bear, the shock almost impossible to endure. A great tree has fallen in our forest of letters. Isidore Okpewho has joined the ancestors.

Novelist, poet, folklorist, scholar, and university administrator, Okpewho was a Jack of many trades and master of all, who left his mindprints on virtually every aspect of African literature and literary studies. With his foundational books, The Epic in Africa and Myth in Africa, Okpewho summoned all his scholarly prowess as a truly First Class Classics scholar and carved out a niche for African oral lore and its inexhaustible possibilities at a time when virtually every claim to high culture and intellectual accomplishment was denied to the ‘Dark Continent’. And his emphasis was on oral lore as a living, throbbing, incessantly regenerative phenomenon, complex, fluently literate in its orateness – a lore which derives its dynamism and fluidity from relentless narratology and performativity. The Oral Performance in Africa, a book he edited some three decades ago with a supremely edifying and authoritative introduction, is a study in this direction. So is Blood on the Tides: The Ozidi Saga and Oral Epic Narratology, (facilitated for the University of Rochester Series by Toyin Falola), his last book which was completed even while he was already ill. In these works, Okpewho’s competence as a Classicist, historian, anthropologist, ethnographer, linguist, literary scholar came to the fore. The result is a series of works enlivened by their author’s astonishing versatility and the irresistible polyvalence of their contents. Okpewho gained world acclaim as a foremost scholar of oral lore, and was elected President of the International Society for the Oral Literatures of Africa (ISOLA), a position he exercised with characteristic dignity, energy, and efficiency.

Without a speck of doubt, the gems garnered from oral lore enriched Okpewho’s treasury as a creative writer. His three novels, The Last Duty, Tides, and Call Me by My Rightful Name, are characterised – and energised – by the kind of orchestration of memory, narrative style, rhetorical immediacy, and vocal vivacity associated with oral narratives. Call Me by My Rightful Name, the most ambitious of these novels, thrives through the mixed medium of orthodox plot sequencing and epistolary narrativity. In this quintessential African Diaspora story, Okpewho astonishes us all with his versatility as historian, anthropologist, musicologist, and the psycho-analyst of race relations and racial selfhood. More than any of his works of fiction, this novel benefitted immeasurably from its author’s calling as scholar/ researcher. I was in a privileged position to know for I watched Okpewho from close quarters as collaborator, Ekiti-Yoruba dialect ‘consultant’, and sounding board while the research which preceded the writing was in progress. He was so mindful of fidelity to detail, correctness of source and story, unalloyed respect for the subjects of his inquiry, appropriateness of names and naming, etc that many times I had to remind him that what he had before him was a work of fiction, yes, fiction, relatively immune from the strictures of crass factuality and academic verifiability. That was the essential Okpewho: hard-nosed scholar, finicky researcher of tremendous integrity.

Any wonder then why I have more than a mere professional interest in Call Me by My Rightful Name? For many years I have taught this novel in my African literature/Literature of the African Diaspora classes at the University of New Orleans, and in every class it has won bright and ardent fans. I used to call Isidore at the end of the semester and regale him with some of the comments (and queries) of my students. And this semester it is again one of the top items on our literary menu. When this afternoon I broke the news of the author’s passing to my class, we had a moment of painful silence – succeeded by a sense of gratitude, sure as we were, that the author of the remarkable book on our reading list can NEVER die.

One area of Okpewho’s many capabilities that may not be widely known is his achievement as academic administrator. For the three years he was head of the Department of English, University of Ibadan, the department bubbled with life and purpose. It was during his headship that the Department’s annual African Literature Conference attracted world-class scholars such as Terry Eagleton and Houston Baker. Okpewho insisted on high intellectual attainment and the maintenance of world-class standard. He had no room for mediocrity, and his own conduct served as exemplum for hard work and prodigious productivity. He knew how to carry colleagues along, even those who might have been intimidated by his sterling achievements.

Nowhere did I see Isidore at his more beatific than in the classroom. The dissemination of knowledge excited him, for he possessed knowledge in admirable abundance, and was passionately eager to share it. He was one of those teachers that just could not resist the celebration of excellence. Many times Isidore came to my office with student scripts in his hand, enthusing; ‘Niyi, just see this. Superb! Isn’t it wonderful that we still have students who can write like this?!’ He invested so much in his students; and the students loved and admired him in return. He pioneered the teaching of creative writing (Prose Fiction) in Ibadan University’s English Department, and broadened the Oral Literature curriculum originated by Professor Oyin Ogunba years before Isidore joined the English faculty. Many of the products of Okpewho’s creative writing classes (Sonala Olumhense, Lekan Oyegoke, Nduka Otiono and others) have become renowned writers themselves, while those who passed through his hands as post-graduate students are now productive professors (JOJ Nwachuku Agbada, Gboyega Kolawole, Chiji Akoma, and many others) in their own right.

And, finally, Isidore Okpewho’s golden gift to the University of Ibadan: the University Anthem. Again, I was witness to the careful birthing of that anthem and Isidore’s intellectual/musical concerns about ‘para-rhymes’, ‘half-rhymes’, ‘eye-rhymes’, and the suffocating strictures of metrical verse. I will never forget that afternoon on the long corridor of the English Department when he showed me the first draft, a half-smile on his lips. My eyes lighted upon two lines that looked/sounded so Biblical in their gnomic simplicity: ‘For the mind that knows/Is the mind that is free’. ‘This is the lyrical, philosophic nugget of this anthem’, I remarked. ‘Thank you for giving us something to treasure…’

Yes, thank you, Isidore, for giving us somebody to treasure. Generous, inspiring teacher, perceptive writer, scholar of no mean repute, you enrich us all with your combination of intellect and integrity, acute seriousness and lightness of being, seamless sense of humour and sizzling vivacity, a consistently compassionate temperament and humane disposition. You have called Life by its rightful name. Its answer is robustly positive and eternally assuring.

Rest well, dear friend

Rest well, noble scholar

Niyi Osundare is one of Africa’s foremost poets and a Distinguished Professor of the University of New Orleans (UNO), where he teaches in the English Department.

PremiumTimes

END

Be the first to comment