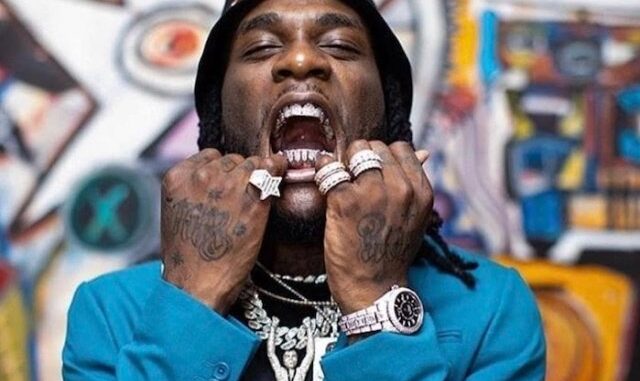

IT has gone down history that Nigeria’s popular musician, Damini Ebunoluwa Ogulu, best known as Burna Boy, became the first Nigerian to win the Grammy, the world’s biggest music award though some Nigerians had earlier been mentioned in connection with minor Grammy achievements.

He was crowned under the World Music Album category for his album, Twice as Tall, at the 63rd edition of the prestigious music event held virtually in Los Angeles on March 14, 2021. It was the second year in a row Burna Boy was nominated in that category.

He beat other nominees like Antibalas, Bebel Gilberto, Anoushka Shankar and Tianariwen. Last year he was beaten by the veteran Beninois singer, Angelique Kidjo. Burna Boy’s Grammy award is significant in one respect.

It is another proof of the excellence that Nigerians can attain in all human endeavours.

Burna Boy’s victory is one of the high points in the build-up of our rhythmic renaissance; a turning point in Nigeria popular music which began in 2009 when two Nigerian Afro-pop artistes, Obumneme Ali and Nwachukwu Ozioko known as Bracket, in their Yori Yori, brought the ‘owewelele’ or what the Yoruba call ‘konkolo’ rhythm, into Hip-hop.

Apart from the brief era of the early Nigerian high-life musicians and the dominance of Fela Kuti, Sonny Okosun and their ilk, the Nigerian music arena had been dominated by Western popular music both on radio and in social life – a state of affairs that music communication scholars described as “cultural imperialism”.

Even in recent years, the Nigerian airwaves and social events had been dominated musically by foreign artistes like 50-Cent, R-Kelly, Notorious BIG, etc. Nigerian popular musicians simply lost out to their Western counterparts because they played Western rhythms, competing outside their own cultural milieu.

Things, however, began to turn around for Nigerian popular music when the Nigerian high-life music, constructed in the 1960s, was deconstructed, reconstructed and imported into the new sound we know today as Nigerian popular music, confirming the writings of Benson Idonije (Burna Boy’s grandfather) that “modern pop music in Nigeria is derived from high-life.”

Three major forerunners of that reconstruction processes were Sunny Nneji with his song, Mr. Fantastic, released in 1998; Tu Face Idibia’s African Queen (2004) and Bracket’s Yori Yori (2009). From there, the buildup continued, manifesting in the works of P-Square, D’banj, Flavour, Phyno, Timaya, Davido, Olamide, Wizkid, onto Burna Boy.

The lesson here can be drawn from Mahatma Ghandi’s words, quoted in UNDP Human Development Report, 1999: “I do not want my house to be walled on all sides and my windows stuffed. I want the cultures of all the lands to be blown about my house as freely as possible. But I refuse to be blown off my feet by any.”

We congratulate Burna Boy and Wizkid.

END

Be the first to comment