A couple of landmark judgements, in which two top public office holders were sentenced to identical jail terms for financial corruption, has raised the public expectation that the judiciary has finally found its mettle in the fight against graft among the country’s elite. Both Joshua Dariye, a former governor of Plateau State and Jolly Nyame, who held a similar position in Taraba State, were pronounced guilty of financial sleaze while in office. The sentencing, albeit belatedly, is instructive, a morale booster in discharging the burdensome menace of endemic graft in the polity.

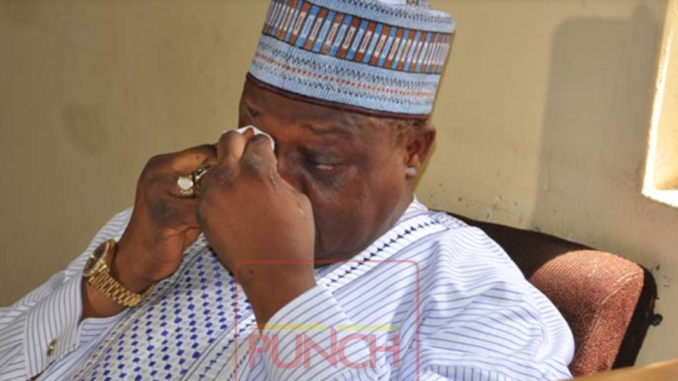

Coincidentally, the ex-governors, who held sway in their states between 1999 and 2007, were convicted by the same High Court in the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja, presided over by Adebukola Banjoko. On June 12, Dariye was found guilty in 15 of the 23 counts filed against him by the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission. On May 30, the judge had also sentenced Nyame to a 14-year jail term for a fraud of N1.64bn. For her boldness and courage, Banjoko stands out among her peers on the Bench, who often treat high-profile accused persons with unusual leniency during corruption trials.

Most significantly, Dariye, a serving senator, converted N1.6bn, which belonged to Plateau State, to his own use. He had collected the money from the Ecological Fund Office in Abuja. He deposited it with his personal bankers, out of which he gave Plateau only N550 million. The rest he disbursed to the Peoples Democratic Party and companies belonging to his associates. He also embezzled some other government funds. During sentencing, the judge decried this: “The defendant was, in fact, richer than his state.” About 13 years ago, Dariye had jumped bail in the United Kingdom, where he was being investigated for money laundering.

In spite of these heart-warming convictions, making the elite to account for their misdeeds in and out of office is still laced with problems. One, the corruption trial of public office holders, like governors and ministers, has faced massive delays since 2007. Two, an effort to fast-track trials through the Administration of Criminal Justice Act, has been rendered ineffective by judges. Third, which is critical, is the suspicious way the appellate courts are overturning the judgements (convictions) of the lower courts. Combined, these factors seriously hobble the crusade to entrench rectitude, transparency and good governance in the Nigerian society.

Going by EFCC records, former governors, including Orji Kalu (Abia), Chimaroke Nnamani (Enugu) and Saminu Turaki (Jigawa), have been on trial for corruption since leaving office in 2007. Ayodele Fayose, the incumbent Ekiti State governor, has been on bail since 2008, although he regained immunity when he won office again in 2014. Some persons have been on trial since 2008 for allegedly misappropriating N774m, money raised for the Police Equipment Fund project, the same year a female senator was granted bail for allegedly mismanaging a health ministry contract. Also, James Ibori, a former Delta State governor (1999-2007), was arraigned on 170 counts, but a court quashed the charges against him in 2009 without even taking his plea. Ibori was later convicted on similar charges by a court in the United Kingdom.

A report undertaken for the Socio-Economic Rights and Accountability Project stated that in the 17 years to 2017, the EFCC and the Independent Corrupt Practices and other Related Offences Commission were able to secure only 10 convictions out of 177 high-profile corruption cases they prosecuted. One of those cases was that of Lucky Igbinedion, a former governor of Edo State, who was convicted but given the option of fine, which he promptly paid. In contrast, between 2000 and 2017, the EFCC secured an average of 100 convictions each year for low-level offenders.

Unfortunately, the noble intention of the ACJA, which the then President Goodluck Jonathan signed into law in 2015, as a panacea for the delay in criminal trials, has been rendered impotent by the wiles and collusion of the Bar and the Bench. Although the ACJA, among other things, makes provisions for daily sittings to accelerate trials, this is not being implemented. Instead, there is pervasive manipulation of the law.

Such tricks include lengthy cross-examination of witnesses by defence lawyers, intimidation of judges through petitions and complaints of alleged bias, technicalities, frivolous applications, filing of no-case submission and constant resort to appeal. At times, these appeals go right to the Supreme Court, leaving the substantive case in the doldrums. In a disturbing pattern, the study reported that the setback in high-profile corruption cases could be traced to preliminary objections (16.55 per cent), interlocutory appeals (14.60), non-compliance with the ACJA (30.28) and suspicious court orders (6.32).

In addition, PEPs still find a solace in the appellate courts. These courts all too easily overturn convictions from the lower courts. Apart from the conviction of Bode George (a Peoples Democratic Party chieftain), which the Supreme Court quashed, the Yola Division of the Court of Appeal, in July 2017, overturned the conviction of Bala Ngilari. Ngilari, a former governor of Adamawa State, had been sentenced to a five-year jail term for corruption in March 2017 by a Yola High court. Jonathan granted state pardon to Diepreye Alamieyeseigha, a former governor of Bayelsa State, who was convicted of fraud.

To deter these tricks, the European Parliament, in January, issued new rules, which demand that a European Union member-state that receives a freezing or confiscation order in respect of a criminal’s property is bound to execute it within 20 days. Similarly, in 2012, the United Kingdom proposed Sunday court sittings to speed up criminal cases. This could be modified here.

Therefore, we strongly recommend a review of the ACJA to address the newly-developed, deceptive strategies that lawyers are employing to hinder cases. The National Judicial Council should monitor the courts and take action against judges who habitually delay trials, while the Nigerian Bar Association should implement sanctions against its members who violate the ethics of the profession. The law should be amended to shift the burden of proof to the defendants.

END

Be the first to comment