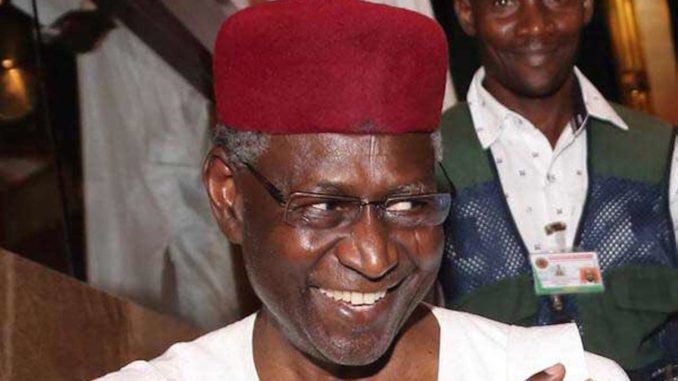

Apparently, the issues thrown up by the death of Malam Abba Kyari, President Muhammadu Buhari’s chief of staff, would linger on in the public domain for a long time yet.

As their flames appeared to flicker, giving sign of burning out soon, the announcement of Abba Kyari’s replacement reignited it all over again. Professor Ibrahim Gambari, a worthy scion of Ilorin Emirate royal family and renown diplomat and scholar, has assumed office as the new chief of staff to the President. With his appointment, analysts of assorted qualifications and backgrounds, are back on the podium with spirited and passionate analysis.

Personally, I don’t have any quarrel with all the things written and said about the departed and the living – they all come with the territory even though some of them are outrightly banal and outrageous. That is what democracy is all about – the freedom to have your say and to tolerate other people’s views, no matter how radically those views conflict with yours. If you are in public office, you may have one or two significant lessons to learn from this kind of exchanges: do your duty to the best of your ability with the fear of God and in consonance with your conscience and the strict mandate of the office. And hope that history may be fair to you.

Some critical questions that the death of Abba Kyari has thrown up include but not limited to the almost untrammeled power and authority that the office of chief of staff confers. Does the office of chief of staff, indeed, make the holder so powerful? As some critics have alluded to, does it make him a surrogate president or prime minister? Unelected, does the holder have the power of the president on whose desk the buck stops?

In attempts to get at some reasonable answers, we have been treated to all manner of sociological and political treatise since the death of Abba Kyari simply because of the larger than life image of the late chief of staff and his visibility, to say nothing about his alleged power and authority, as the highest-ranking member of the Executive Office of the President.

But with no clear answers, the questions are even beginning to change focus. Now they ask: Can Professor Ibrahim Gambari, though a renowned diplomat, seasoned administrator and even former minister and scholar, step seamlessly and successfully into the shoes of the departed? Unfortunately, it is not in my place to answer these questions either way.

Having said so, I have a modest contribution to make in the form of intervention that is designed neither to praise nor to vilify the former occupier of the office or even to assess the capacity of the new chief of staff, but hopefully to provide insight into the evolution of this all-powerful position.

It is therefore appropriate to say over and over again that this is not the first time this country would have a chief of staff to the president. Nigeria, since President Shehu Shagari’s tenure from 1979 to 1983, has had five chiefs of staff at different times, Professor Gambari being the sixth.

Unelected, all of them, I dare say, were as powerful and as effective as their respective principals wanted them to be. Not only were they unelected, their roles are not specified in the constitution; not in the extant laws of Nigeria nor those of the USA where the concept originated way back in 1961.

It started as one of those very important administrative and managerial duties usually performed by any intelligent, even if minor, staff in the presidency with any nomenclature that the appointee deems fit.

The White House Chief of Staff, this glamorous position – power-packed and influential – evolved from a humble beginning. The roles of the private secretary to the president, personnel, scheduling, coordination of information, control of the president’s travels and movements among others, were formalized and given the title of assistant to the president in 1946. In 1961, it metamorphosed into something more elaborate to include being in custody of policies and programmes, and was conferred with the title of Assistant to the President and Chief of Staff. This has remained the full title till date.

But today it carries a lot more responsibilities. And the holders of the office have wielded enormous powers and exercised delegated authorities, the type not available in the British Westminster parliamentary system in which the prime minister and members of his cabinet are elected members of parliament and where they routinely give account of their stewardship on the floor of the house.

But not in the all-powerful Presidential System where one man is super powerful, subject only to the checks and balances imposed by the constitution. In all cases, the buck stops on the desk of the president. He takes credit for the good work of his unelected assistants and gets the blame for their shenanigans as well – that is why he can hire and fire at will without recourse to any other authority.

The relationship between President Ronald Reagan, a former Hollywood star, who was a very successful American president from 1981 to 1989, and his chief of staff, Donald Regan, typically illustrates the kind of synergy required for the smooth running of the White House. Their relationship is still cited today as a typical example of the power and influence such ranking Presidential aide can exercise.

Regan, not to be mistaken for Reagan, the President, started his career in the White House as Secretary of Treasury where in four years, according to records, he helped to revolutionize the U S economic policy which also paved way for reform in the tax system. In the second term of the Reagan presidency, Regan stepped in as the CoS and he started a tenure that witnessed lots of intrigues and personal rivalry.

As chief of staff, the citizens came to regard him as the “ second most powerful person in the United States.” And for good reasons. The president had taken ill in July 1985 and was in the hospital awaiting surgery.

The duty of getting the Cabinet and leaders of the Senate informed of this development devolved on the chief of staff. But he could not freely carry out this onerous responsibility without clearing it with Nancy Reagan, the First Lady who also depended on her astrologer friend in San Fransisco to give the green light. The astrologer must tell them the right time to do anything in the White House. Surgery which is a life and death matter had to await the approval of the First Lady and the astrologer. As for the anxious Cabinet members and leaders of the Senate, none of them could possibly reach the president without Regan’s say-so.

Even when Robert MacFarlene, the national security advisor, sought desperately to reach the president on international security matters, mum was the answer he got. Between the chief of staff and the powerful First Lady, the gate was impregnable. It took George Bush, the vice- president, three hectic days of peeping and waiting for the chief of staff to give him the go-ahead to see the president. But unknown to the public, the President’s directive was cast on stone and it was very clear: keep the number of visitors to the minimum. And there was to be no exception.

Naturally, the country was agog with wild gossip and the angry press could not be mollified until Larry Speakes, the White House spokesman, came out to clarify the situation thus: “The Chief of Staff is not making any decisions that the President does not want him to make.” End of discussion. The country now knew where the powerful CoS got his powers from.

Now, are we to expect a posthumous respite for late Abba Kyari and some little elbow room for Professor Gambari to settle down and perform?

END

Be the first to comment