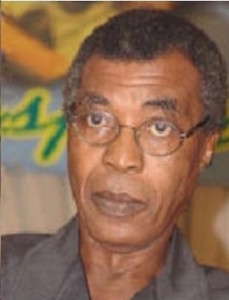

Today marks the Tenth Anniversary of Dr. Bekololari Ransome-Kuti’s unexpected passing on February 10, 2006. Born in August 1940, Beko was a young-ish 66 in 2006 when the grim reaper came calling. But by then, he already amassed a full life’s body of work. This was attested to by the stream of eulogies that poured in from across the social spectrum as news of his demise spread. Tellingly, the most endearing tributes came from the upper crust of the same political class Beko that spent a good chunk of his activist life battling and trying to reform.

There is a distinguished canon of medical practitioners who famously set aside their stethoscopes and embraced the life of writing, or at the very least navigated easily between wards and words. Anton Chekhov, John Keats, and our own Wale Okediran are exemplars.

Trained at the University of Manchester, Beko belonged to this tribe of the surgical knife. But a writer he most certainly wasn’t. In fact, not only was he not a writer, in the latter part of his life, as his renown as a social justice activist grew, he resisted all pressure (the poet Odia Ofeimun and journalist Kunle Ajibade for instance were unrelenting) to set down an account of his life.

In lieu of writing, what he did do was organise and act. Engels once said that “an ounce of action is worth a ton of theory.” It is not clear if Beko, a voracious reader, encountered Engels; but there is no doubt that he believed in, and was committed to, the power of political action to change the world. Together with the doughty Femi Falana and the irrepressible late Gani Fawehinmi, he formed a triumvirate that, in the 1990s, was quite literally the elite face of the struggle to dislodge the military from power in Nigeria.

Beko was simultaneously the most likely and most unlikely person to become an activist. Both Falana and Gani were shaped by a university education in which arguably more time was spent on the hustings than in the classroom. From all accounts, Beko had no such distractions (admittedly, there were others) as an undergraduate. Yet, being the son of Funmilayo Ransome-Kuti and the brother of Fela, he could of course (this is the likely part) point to a filial pedigree steeped in activism. But as every student of society knows, belief in a good society is never genetically transmitted, and it is not implausible that he, Beko, remained immune from ‘radicalism’ until the 1977 Kalakuta episode in which he lost his mother. After that, and especially with his constant exposure to the ravages of military rule as a medical doctor and leader within the Lagos branch of the Nigerian Medical Association, he was thrown into a life of political confrontation.

I mentioned above that Beko was the most unlikely candidate for rugged activism. In saying this, I had in mind his physique. He was on the slight, even wiry, side, and my first meeting with him, in the company of Babafemi Ojudu (my boss at The News), on the trail of confidential information to back up an exclusive news story, left me hugely deflated. Beko seems to have spent more time attending to his Nietzschean eyebrows, which he held on to in the manner of a life raft, than the two guests-Ojudu and myself- sitting across his table and hanging on to his every word.

Yet, as everyone who stumped and worked with him knew all too well, his unprepossessing physical frame belied a deep-seated conviction about democracy, social justice, equality, and the total organisation of human society. He needed the security of that conviction, as time after time, he endured jail and emotional deprivation in the hands of a succession of military thugs. One of those thugs is thankfully no longer with us. Another currently resides in Minna, busily gorging himself on his loot, posing as a statesman for a state that isn’t.

After my first visit in Ojudu’s company, I was rewarded with other invitations, and the more I saw of the man, the more my affection for him and what he stood for grew.

It is true that Beko was one of the major personalities in the Nigerian democratic movement at a critical conjuncture in the country’s not too distant history, one in which a misspoken sentence could, and often resulted in, a lengthy jail sentence; and to remember him now, ten years after his passing, is to remember a generation that, amid internal tensions and state-manufactured divisions, handed Nigerians the possibility of constructing a social order that can produce the most good for the greatest number. It is to contemplate a pantheon of heroes, living and dead, including Chima Ubani (who died tragically in 2005 at the young age of 42), and several others whose names are too numerous to mention here. It is also to contemplate, on a more somber note, the diminution of the civic energy of the 1990s, the unraveling of the Nigerian student movement, and the overall reformatting of the public space, mostly in a form contrary to the fundaments of the kind of society that people like Beko believed they were fighting for.

This brings me to the reason why I was drawn to Beko, and why, almost three years ago, I decided to take a stab at writing his biography. There was Beko the medical doctor who morphed into an activist. But there was another Beko, the atheist. Both, suffice to say, are of a piece, as follows: Beko was driven to the cause of social justice, I am now inclined to believe, by his humanism, which was bound up with his atheism. He wanted Nigerians to live a better life, and he spent the better part of his adult life fighting to bring us closer to that possibility. But fundamentally, all he wanted was a better human society, period. As an atheist, he rejected all religions as basically superstitious and uniquely rigged to deny human agency and perpetuate human misery.

Beko’s secularism offers a perfect template for the analysis of his life and politics. Such a task has never been more urgent given the continuing evisceration of our social life by pseudo-religiosity. Beko’s was a life lived without religious illusions, but instead in unstinting dedication to the pursuit of social justice. It is a life that continues to recommend itself, and just like the life of Tai Solarin, another inimitable humanist, must be commended to the next generation.

Rest in peace, Baba Agba.

PREMIUM TIMES

END

Be the first to comment