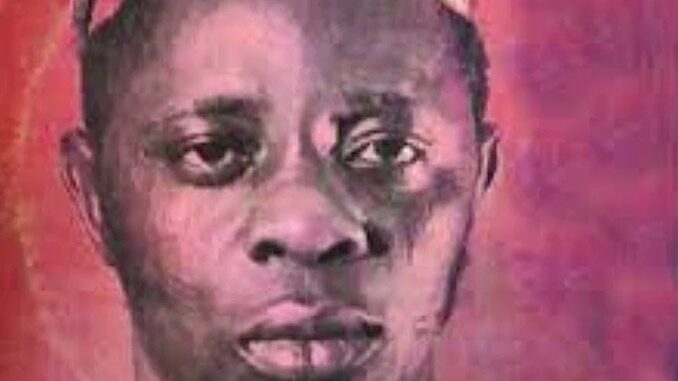

Ayinla Omowura, was a prodigy unlocked, he sang his heart out on this side of existence and sang himself to the peak of Apala music. He apparently also died with music still locked up inside him. He couldn’t read or write, he composed and sang directly from his heart. He was a veritable example on music as the literature of the heart.

What was the sound of music before the intrusion of microphones, mixers and other Western accouterments? Often, I imagine how music might have sounded back in Eden, without digital manipulations and the contemporary crutches. I suspect my taste for primordial tunes was shaped back in childhood. I was weaned on Waka; the types of Nosimotu Alimi and Batile Alake. Haruna Ishola inducted me into Apala with the immutable cadence of Rafiu Ojubanire, his lead drummer. Lefty Salami and Yusuf Olatunji tuned me to Sakara music at an early age.

I remember the expansive gramophone in the rectangular sitting area upstairs, where my father sometimes invited us to dance around the centre table as Apala or Sakara played under the green fluorescent lamp in the cool of evening. My feet were made of bronze and I rarely sang but I knew the lyrics by heart; my more genial sister, Nihinlola, always danced her hearts out for whatever token father gave for the night.

I.K. Dairo, Daniel Ojoge and Dele Ojo ruled the Juju scene of that childhood. I nearly forgot Suberu Oni and the Why Worry Band, led by a folksy duo at the local Juju scene in Ondo town. Not a more disparate and yet congruent musical pair has been made since Suberu and Oni, one was tall and stocky, the other short and austere; the stocky one sang in a deep unaffected baritone, the austere man crooned delectably in soprano.

Rex Lawson, Victor Olaiya, Joe Mensah and Adeolu Adesanya in those days rocked the Highlife scene in Port Harcourt, Lagos, Ibadan and some strange, faraway world from my place of birth. Sunny Ade and Ebenezer Obey, Juju maestros, belonged in the prodigious womb of the future.

He arrived almost steaming hot, always crooning that he was the best, that Apala music would not be the same again after him, and he delivered on these promises. Omowura remained in Apala and reckoning, until his avertable death in 1980, in a bar room brawl. He remains a major definition of the genre till date.

You had no problem in the late 1960s thinking Haruna Ishola was in total control of Apala music; you might even be tempted to think he held sway on that genre in perpetuity, until Ayinla Omowura showed up in 1970. Omowura did not arrive pussyfooting into the Apala scene and prominence, he did on the EMI label, an elite recording company in Nigeria at the time. He arrived almost steaming hot, always crooning that he was the best, that Apala music would not be the same again after him, and he delivered on these promises. Omowura remained in Apala and reckoning, until his avertable death in 1980, in a bar room brawl. He remains a major definition of the genre till date.

Lady Gaga, a freaky pop sensation counsels, “it is the duty of a musician to have mind-blowing, irresponsible, condomless sex with whatever idea they are singing about”. That artiste thinks music is no vocation for the faint-hearted; that the musician should neither be restrained by politics, ethics nor pathos but go wherever the muse leads. The songstress most likely never heard of the Egba-born maestro but it seems Omowura might have hewed his philosophy, prefiguring the counsel of the American pop star.

Ayinla romped with whatever idea he sang about and he sang about anything that caught his fancy. He was apparently fascinated by everything. From his danceable tracks on the 1972 National Population Census, to 1973 Lagos Rent Edit, and 1976 Owo Udoji (Udoji Awards) you might think him a government megaphone. But he was also a social crooner, a peculiar crusader; a moral police often at odds with women. He waxed acerbic lyrics on disrespectful wives (pami’nku obinrin), jealous wives (obirin oj’owu), and wayward wives (oni’bambashi); women who question male authority or challenge philandering husbands. The musician reserved special laceration for ladies with bleached skins and female owners of beer parlours. Listening to Ayinla Omowura on women and morality, you may think the man as an angel, especially if you didn’t know he too was a womaniser, a serial philanderer, that he was not a teetotaler.

…Ayinla Omowura literally took death to the cleaners… Ayinla assured that death would not get him until he was old, bent and ready. You then imagine what his thoughts were in 1980, when he came face-to-face with the disheveled being and the fatal club, at merely 47 years.

Ayinla was also fastidious about death and he engaged the subject many times before his demise in 1980. Death to the artiste is not an esoteric or a spiritual force but a dreadfully dark persona with fiery eyes and a fatal club. He waxed many lyrical elegies on death in his prodigious career. The imagery of the dreadful one with the fatal club pervades the artiste’s elegy on Murtala Mohammed, Nigeria’s military ruler who, in 1976, fell in a bloody coup; Yusuf Ajao Olatunji, the Sakara maestro who died 1978; and Wahab Amode Maja, the seriki of Egbaland. But Ayinla Omowura literally took death to the cleaners in his elegy on the latter. He applied a new brush on his image on death, depicting it as foolish and disheveled, an irresponsible being that thinks nothing of employing fatal bludgeons on the human race. Ayinla assured that death would not get him until he was old, bent and ready. You then imagine what his thoughts were in 1980, when he came face-to-face with the disheveled being and the fatal club, at merely 47 years.

A 19th Century British prime minister, Benjamin Disraeli, wrote that most people die with music still locked up inside them. Ayinla Omowura, was a prodigy unlocked, he sang his heart out on this side of existence and sang himself to the peak of Apala music. He apparently also died with music still locked up inside him. He couldn’t read or write, he composed and sang directly from his heart. He was a veritable example on music as the literature of the heart.

It has been 40 years since the music stopped and Apala still struggles to fill the space. Omowura fans had planned big for the 40th anniversary of his death on May 6 this year; then the virus came and smothered their plans. But it couldn’t smother Ayinla Omowura – Life and Times of An Apala Legend, a 537-page book by Festus Adedayo. The book goes behind the curtains to sculpt the man. It is a compendium on the public and private life of the musician – glitz, warts and all. There, you will find Ayinla Omowura was human, just like the rest of us; that his beats may sound Edenic but some lyrics could sway far from Eden.

Wole Akinyosoye writes from Lagos.

END

Be the first to comment