With the 2019 general election a few months away, the pervasive use of money to influence poll outcome remains an albatross in national politics. Chiefly, the blatant recourse to vote-buying by politicians in the governorship election in July in Ekiti State accentuated its reality, causing anxiety among Nigerians. Sharing or distributing money has also occurred in a series of rerun polls for national and state assembly seats across the country. It is a nightmare for the Independent National Electoral Commission. To curb this perfidy, the anti-graft agencies should collaborate with INEC to bring those guilty of this abuse to book.

As a habit, it is entrenched. Right from the time they declare their intention to contest, politicians negotiate the murky waters to office by using money and material gifts to woo the electorate to their side. During elections – as witnessed in the last governorship elections in Ondo and Anambra – politicians openly buy votes. INEC lamented the farce in Ekiti, condemning “the rising phenomenon of vote-buying.” This is a subversion of the electoral system. For this, Nigerian elections are always deemed to have fallen short of global standards as the results don’t reflect the true will of the voters.

However, the system has in-built mechanisms that can tame the phenomenon. The Electoral Act, an offshoot of the 1999 Constitution, empowers the electoral umpire to bring those who compromise the system to justice. Sections 88 and 90 of the Electoral Act 2010 are integral to this. Section 88 bars candidates from receiving funds from outside the country for electioneering, while Section 90 codifies the limits of spending by candidates.

For presidential candidates, the limit is N1 billion. The ceiling is N200 million for governorship contestants; N40 million (senate) and N20 million (House of Representatives). Likewise, an individual or a body corporate cannot donate more than N1 million to a candidate’s campaign. These are excellent legal provisions, as punishments are also provided for breaches. Nevertheless, by refusing to subject pre-election spending to any limits, wily politicians manipulate the system to their advantage. It taints our elections.

The 2015 polls underscored this open sore. In the run-up to the ballot, allegations of bribery rent the air. Shortly after, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission began to prosecute 202 serving and retired INEC officials in 16 states for collecting bribes to rig the polls in favour of the ruling party then – the Peoples Democratic Party. An INEC official is facing charges of receiving a bribe of N112.4 million; five Resident Electoral Commissioners and a national commissioner were also indicted for benefiting from the $115 million (then N23 billion) allegedly disbursed by a minister.

Unfortunately, this ailment is contagious. For members of the National Assembly, they manipulate the system by deploying part of their constituency project votes to entice the electorate. So, through it, they have access to slush funds to buy votes. This is where sewing machines, motorcycles, wheelbarrows, generators, cash gifts and grinding machines come in. It is not the duty of lawmakers to execute projects. Their constitutionally assigned duty is to make laws.

In former President Olusegun Obasanjo’s two-term tenure, the Senate allegedly demanded bribes before confirming ministerial nominees and approving the budgets of Ministries, Departments and Agencies. In his book, The Accidental Public Servant, Nasir el-Rufai, currently the Kaduna State Governor, narrated how senators demanded bribes to confirm him as a minister.

The judiciary is not immune to the rotten culture. In 2016, the National Judicial Council recommended to President Muhammadu Buhari the dismissal of three senior judges. An NJC statement then stated that one of them had demanded a bribe of N200 million to influence a 2015 election petition before the Owerri Division of the Court of Appeal. The EFCC put another judge on trial for allegedly collecting bribes to delay a 2011 pre-election case in Ogun State. The case suffered legal delays until the petitioner’s allotted four-year term ran out.

In comparison, the laws on election spending are strictly enforced in Canada, the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom, among other places. In the US and Canada, it is either candidates access public fund or they reject it and raise their own fund. In Canada, a candidate cannot donate more than $5,000 to his or her campaign, the Elections Act states. In the UK, the system encourages short and relatively inexpensive campaigns.

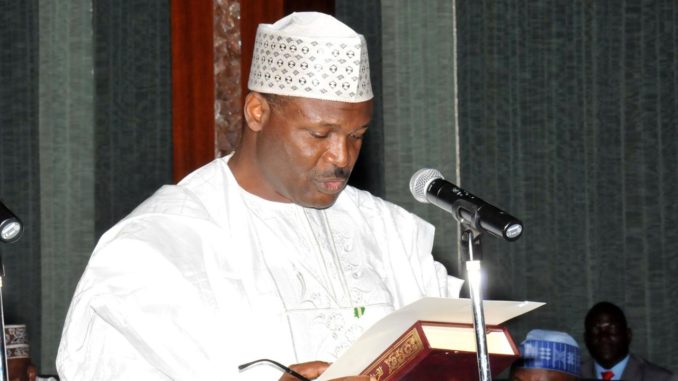

Fortunately, INEC has a golden chance to redeem itself in the September 22 governorship ballot in Osun State. Already, the Yakubu Mahmoud-led commission has outlined measures to curb vote-buying. For instance, INEC said it discovered that cell phones were used to snap the photographs of the party/candidate people voted for in the Ekiti election. The photographic evidence was later presented to party officials, who gave out money. In reaction, INEC has decided to ban mobile phones at polling booths in the Osun election.

It is a sensible action. However, going by the desperation of politicians, it might not be enough to deter them. As the 2019 polls draw nearer, INEC has to be more proactive. The security agencies should be truly independent.

With Section 225 of the 1999 Constitution, INEC can sanitise the electoral system. The section mandates parties to submit their financial statements, including the sources of their funding to the electoral body on an annual basis. A thorough auditing of these accounts might provide the legal grounds to move against those who undermine the system with their resources. To stamp out the malaise, therefore, INEC should enforce the law.

END

Be the first to comment