In a way, the Hanoi ceremony of three weeks ago could be said to share a parallel with just any of the legend’s own epic duels that went the distance in the rope square. As visiting President Barack Obama happily announced the lifting of a 50-year arms embargo on Vietnam, it could as well be the declaration by an overly excited umpire in shimmering tuxedo of the scorecard after a fistic explosion before a delirious crowd inside a tense coliseum.

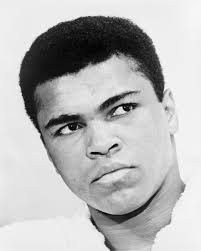

While diplomats on both the American and Vietnamese sides could be pardoned for basking in the effulgence of that electrifying moment that has hopefully finally brought a closure to a bitter memory between Uncle Sam and the South-east Asian nation, the ultimate moral garland undoubtedly belonged to just one man: Muhammed Ali.

Ali’s conscientious objection as a world heavyweight champion in 1966 to being drafted by the US to fight in Vietnam, voiced in a language that spoke to the blacks’ prevailing dire condition in a bitterly segregated America, not only created a moral baggage for the meddlesome super power, it turned out to be the defining moment of his remarkable sporting career.

The omens from the Arizona deathbed last Friday should then not be mistaken. Like the strange night he endured pain and stretched the human will beyond limits in Kinshasa to overpower the monstrosity of George Foreman, Ali soaked all the blows from a cruel Parkinson Disease for more than three decades to witness imperial United States grow penitent and its president stand on the Vietnamese soil to announce a repeal of a punitive policy made 50 years ago.

Not until Obama lifted the symbolic arms embargo against Hanoi last month did “The Greatest” finally take a bow from the ring of life. It was as if he waited for America to be morally pummeled to submission before he agreed to draw his last breath in the Arizona hospital last Friday night.

America’s change of heart was first demonstrated in 1995 with the normalisation of diplomatic relations with Vietnam under the Clinton administration. President Bill Clinton followed that with a state visit in 2000. A reconciliation that was continued by George W. Bush with another visit in 2006. Perhaps, the Medal of Freedom Ali received from Bush in 2006 was to say sorry.

Indeed, had the Swedish Academy in Stockholm itself not become sucked into the vortex of international politics, were the colour of a man’s skin still not a big factor at that age, that singular act of denunciation of war by Ali at a huge personal cost should have earned him a Nobel Peace Prize that decade.

In hindsight, it is probably now much easier to situate such omission. While the Nobel faculty is ordinarily expected to affect the air of independence, it was probably considered too dangerous then to fete someone seen as the No. 1 enemy of the American establishment given the intense emotion Vietnam evoked at the time.

But without the Nobel stripe, Ali proceeded to achieve immortality. Beyond the euphoria of being coronated world champion in 1964, he realised early enough he was now accountable to not just the fans baying for action at sold-out arena but to a much broader, international constituency, the community of the oppressed.

Justifying his pacifist resolution, Ali famously declared: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong. No Vietcong ever called me nigger.

“I’m expected to go overseas to help free people of South Vietnam, and at the same time my people here are being brutalised and mistreated, and this is really the same thing that’s happening over in Vietnam. So, I’m going to fight it legally, and if I lose, I’m just going to jail. Whatever the punishment, wherever the persecution is for standing up for my belief, even if it means facing machine-gun fire that day, I’ll face it.”

The thunderous effect of those defiant words on the white supremacists who dominated the US establishment then was better imagined. The country was already quaking in the ferment of the Black Freedom struggle whose storms started gathering in the 1950s. Across the Atlantic, the gale of decolonisation was also ripping down Africa.

For his conviction, Ali paid a huge price: forfeiture of his hard-earned boxing jewel, fortune and a jail term. Most harrowing perhaps was the wasting of the peak of his youthful energy and agility. In the times ahead, life grew really so desperate that the people’s champion had to depend on little pay cheques from speaking engagements on campuses to survive. As civil rights icon Martin Luther King Jr. observed then, “He’s giving up millions of dollars to do what his conscience tells him is right.”

The punitive judgement was not set aside until three years later by the US Supreme Court in a unanimous ruling. Only then was his boxing license and source of livelihood restored.

In retrospect, as Ali’s remains are interred today in his native Louisville, it will be a poor reading to describe the Ali enigma as defined only by a prodigious boxing talent. Beyond the ring, he more than embodied the struggle of not just the American blacks but all the underdogs of the human race for equality in the 20th century, with a name that resonated and a face that was easily recognisable globally. Within living memory, only a few other luminaries could in fact be said to have come close in terms of the universality of the appeal of the Adonis from Louisville.

He was not necessarily the heaviest puncher of his generation, but was arguably the smartest, forever reaffirming the primacy of the brain over brawn. No other fighter in history ever “floated like butterfly” or “stung like bee”. There was poetry in the way he jabbed and gyrated in the ring. But more than that virtuosity was an iron courage and a steely character.

Just as he was good at peppering opponents with his sharp tongue, the “Louisville Lip” was equally a master of self-deprecating humour. After his result in the Army aptitude test in 1964 was put at 78, therefore “unfit for military services”, Ali quipped “I said I was The Greatest. I never said I was the smartest.” (Desperately needing more recruits for Vietnam two years later, the Army would dramatically reclassify him 1-A – fit for service).

After being knocked down with a treacherous left hook by Henry Cooper in London in 1963, he remarked with a straight face, “When I found myself on the canvass, as The Greatest, I found that very embarrassing myself.” To the typically staid British Cooper, who was later dispatched in Round Six, Ali jabbed, “You’re not as dumb as you look.”

With personal example, Ali demonstrated true greatness is not in never falling, but in the ability to come back again and again after a fall. The bravery he exhibited in the face of mortal danger in the ring by winning the world title thrice as underdog was only equalled by an unwavering commitment displayed outside to the promotion of the cause of healing, peace and justice worldwide.

Once in the early 70s, Ali’s providential presence saved a suicidal black man from plunging from a highrise in the US. That day, a multitude had gathered and looked to the sky as the man readied to make the final dive. Then, word reached the charismatic champ who was driving by. Quickly, he jumped down from the car, bolted across the highway in a dark suit and raced up the stairs within the twinkling of an eye. Soon, he was standing close to the man up there and uttered: “Hey, I’m Muhammad Ali and your brother.” Though few, those words proved magical. They rekindled hope in the man who instantly stepped back from the precipice and locked the champ in a tearful bear hug.

Little wonder then that even as he became enfeebled and entrapped in a body that was no longer functioning, his stature was in no way diminished as a formidable moral force. Monosyllables he whispered in great difficulty in some moments of global moral crisis were enough to force kings and nations to action.

Only last year, a mere letter from him led the usually stone-hearted Iranian authorities to unchain a Washington Post journalist, Jason Rezaian, in Tehran after 545 days in captivity.

In his twilight, much more remarkable was the grace and dignity he showed in the face of indescribable physical pain. The last thing he ever wanted was pity from the world he once mesmerised with the dizzying speed of hands and the dazing alacrity of the feet.

While the world bids “The Greatest” farewell today, this writer mourns a personal loss. Besides one’s parents, Ali is clearly the next person that had the lasting influence on one as a child. Had writing not taken me, I can tell straightaway that I would have had a career in boxing, inspired solely by Ali. I grew up listening to and reading his folklore and watching his ring exploits on the Black & White television.

By the time I entered Victory College in Ikare, Ondo State in the early 80s, that passion drove me to enroll in the school amateur boxing club. Our school principal then, Chief Seinde Arogbofa (presently the Secretary-General of Afenifere) forever admonished us never to dream small, whether in academics or sports.

We had Coach Awodeyi to put us through the rudiments of “the noble art of self-defense”. Every other day of the week, we jogged kilometres in the morning. We shadow-boxed. We punched the bag in hand-gloves that were oversized. There were ethics to learn: don’t hit the below the belt nor after the bell. We sparred.

At the training, everyone wanted to dance, bob and sting like Ali. With both gloved hands raised up to the temple on guard, we would lean on the ropes of an imaginary ring, aping rope-a-dope, seeking to tire out the adversary. Blow after another ferocious blow, uppercut after another vicious uppercut, we learnt the true meaning of perseverance in pain, personal responsibility for victory in combat and gallantry in defeat.

Once, after a grueling three-round fight with a quarry at an inter-school competition in Akure, I remember my opponent’s coach came over to my corner and earnestly asked if truly I wanted to further my boxing career. He promised to make me a world champion if I followed him.

By my fourth year in secondary school, writing took over. In place of jabs, I learnt to hit with words.

But boxing never left me. As reporter, other than politics, one sector I could effortlessly write and comment on is boxing locally and internationally on account of not just an enduring deep passion for the game but also a sense of shared kinship with the gladiators who animate the ring.

As news of Ali’s passing spread early hours of last Saturday, the first call I received was from perhaps Nigeria’s “only surviving communist”, Comrade Kayode Komolafe. He called to personally commiserate with me. You would think Ali was my biological relation. Being my senior professional colleague, KK acted out of an intimacy made possible only by a brotherhood.

When twenty years ago (1996) Mike Tyson infamously bit Evander Holyfield ear in a world heavyweight title fight in the US, the newsroom of Sunday Concord was bitterly divided between my brother and friend, Segun Adeniyi and I. I was Tyson’s diehard supporter while “Pastor” Segun naturally backed Holyfield, not based on any particular interest in boxing other than, I guess, his merely professing to be a Born Again Christian. (Segun is ordinarily a soccer fan).

Veins literally stood in our necks as we continued to argue fiercely over who was right or wrong between the two American pugilists. You would think we stood to share personally in the millions of dollars Tyson and Holyfield cashed for the night.

But our editor then, Mr. Tunji Bello (present Secretary to Lagos State Government), saw a big story in the raging quarrel in the newsroom. Fearing things could degenerate to real fisticuffs, he stepped in and directed us to put our anger in writing. Thus emerged a great copy entitled “Crossfire” between Segun and I in the next issue of Sunday Concord. Bello’s deputy then was Sam Omatseye. While KK was senior editor of the Editorial Board.

True legends inspire generations. Ali lives.

PREMIUM TIMES

END

Be the first to comment